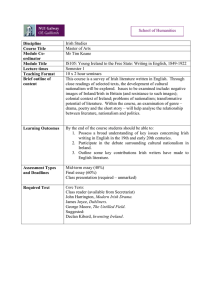

Monsignor Padraig de Brun Annual Commemorative Lecture 2013 Maurice Hayes

advertisement

Monsignor Padraig de Brun Annual Commemorative Lecture 2013 NUI Galway 25 February 2013 Maurice Hayes To Hell or Croker – Whither the Irish Public Service? I What indeed is the future of the public service between those who would consign it to perdition, on the one hand, and those who would insulate it from the cold winds of reality and change in the comfort blanket of the Croke Park Agreement? I pose the question in all innocence. What has happened to the service I was proud to work in for most of my career, and to the fine people I worked with in the public service, North and South, that it should now be reviled as unfit for purpose and exposed to insult and obloquy, and worse, to derision and ridicule. And yet it is not so long ago since that archetype of the ideal public servant, T K Whitaker, was selected in a popular poll as the Irishman of the century – epitomising the values of honesty and impartiality, respect for the law, respect for persons, diligence, responsiveness and accountability, which were invoked recently by a senior Irish Civil Servant, only to be sneered at with crude philistinism by the Chair of the Public Accounts Committee, dismissed contemptuously as “Corinthian”, as irrelevant in a world which requires the more realistic values of the market place, the banks, the bond-market and the counting-house. Not much of a choice, you might think, given the lack of anything approaching Corinthian values, or even simple morality, in Lehman Brothers and the Libor banks. It was not the guys in hair shirts who got us into trouble but the men in mohair suits and dress-down denims. On the other side of the equation, there is the largely self-inflicted wound of the public service seeking to protect themselves as a caste from the worst effects of the collapse (for which they are popularly seen to be at least partly responsible) which is effecting those in the more exposed parts of the economy. At the most senior levels it betrays a lack of leadership, an unwillingness to share the common burden or to put the common good before personal privileges and protected pensions which should exemplify the true Corinthian, and the insistence of trade unions on the inviolability of pay and conditions. The fall from grace of the civil service and the loss of public esteem parallels the crumbling of other great pillars of society, the church, the banks, the political parties, and the decline of deference and the loss of respect for the priesthoods associated with them. There is no reason why the public service should be protected from the societal judgement, 1 should not have to answer for its shortcomings, and should not have to win back public confidence and find a new and currently more relevant role for itself. The first and main challenge for the public service is to regain public respect, to recover the public trust which has been lost, and to restore the parallel loss of morale which has been shattered by mindless criticism on the one hand and blind self-interest on the other. The next is to restructure and re-equip to meet the needs of a changing society; and then to find the people who can deliver on both objectives at a price the nation can afford. Having worked all my life in the public service, I am a firm believer in the need for a competent, efficient and dedicated public service as part of the machinery of a modern democratic state. In reflecting on the difficulties facing administrators in a much more complex world, I want to dispel any impression of the old soldier “shouldering his crutch to show how fields were won”. . II The public sector is a broad field, stretching from those who deliver services on the ground to those who merely offer advice, and including in between many professional and occupational grades and those who regulate, manage and administer. However my focus, in the main, will be the civil service and the higher echelons as the group I know best. They are also the people most often castigated either as remote mandarins or as idle parasites. Most people make favourable comments about the front line workers, while the shadowy figures in the background can be vilified as power-hungry manipulators, as faceless men, uncaring calculating machines, or out of touch amateurs unable to comprehend the complexities of modern society. I believe that a permanent civil service performs an important and necessary function as a balancing mechanism in the machinery of government, particularly when political power shifts in the electoral cycle (and as a brake on autocracy when it does not), and although not specifically mentioned in the Constitution (largely because deValera did not want to concede the role) as an important fifth estate in Irish governance, The existence of a permanent non-political civil service we owe, if I may breathe his name within shouting distance of the Fields of Athenry, to the much reviled Charles Trevelyan who argued in 1853 that “the increasing burden of public business could not be carried on without an efficient body of permanent officers , occupying a position subordinate to Ministers, yet possessing sufficient independence, character, ability and experience to be able to advise, assist, and to some extent influence those who from time to time are set above them.” The Northcote-Trevelyan Report was seminal in laying the foundations in the British system for a permanent professional corps in which competitive examinations replaced patronage as the main form of entry, which valued the qualities of the rounded humanist 2 over those of the specialist, the advisor and counsellor over the advocate and the policymaking skills over the executive (values which, it may be noted, are now being questioned on their home ground). Máirtín Ó Cadhain, in a short story, recounts the defiant cry of an old lady in Connemara, harassed by neighbours shortly after the foundation of the state; Níor imigh dlí nuair d’imigh Sasain! Well, Níor imigh an stat-sheirbhís ach oiread. They hadn’t gone away you know! The Irish civil service, North and South, and the values and integrity of public service (the now derided Corinthians) which have endured in a relatively incorrupt civil service descend directly from Northcote-Trevelyan. The founding fathers of the Irish service, Brennan, Moynihan and the great McElligott were Treasury men who brought with them the same bleak integrity and the same almost Carthusian frugality. The Northern Ireland service included some who had moved north from Dublin Castle, among them the abundantly named Andrew Reginald Nicholas Gerald Bonaparte Wyse, from Waterford, a weekly commuter from Dublin, and the only Catholic Permanent Secretary until Paddy Shea was appointed to Education (Wyse’s old berth) in 1969. Not in my time, but late into the post-war years, and living on in the race memory were some exotic creatures, enjoying a half-life under the title of Existing Irish Officers, clinging to the customs and privileges of a former existence, entitled to drift in at ten in the morning and to leave at four to suit the schedule of the Kingstown train and not subject to a retirement age. Before we laugh too much at such quirky and anachronistic privileges being maintained through the hungry thirties and the privations of the war years, we might look round and reflect on those who now wish to keep open every last isolated police barracks vacated by the RIC in 1922, or those who battle under the banner of Croke Park for the retention of every idiosyncratic bonus or allowance accreted over the decades in circumstances which no longer exist, and regardless of the ability of the State to meet the bill. III A great benefit of a permanent, non-political civil service is continuity, especially in the face of a change of regime. The Irish civil service, having managed the setting up of a new administration, coped with what was a defining moment in the development of the emerging Irish democracy, the transfer of power from Cumann na nGael to Fianna Fail in 1932 – and again the transfer of power from Fianna Fail to an All-Party Coalition in 1948, and successive changes of regime thereafter. 3 In Northern Ireland, after fifty years of undiluted Unionist hegemony, when the yardstick later articulated by Margaret Thatcher “Is he one of us?” was the main determinant of most appointments, the most fundamental regime change of all was effected with the suspension of Stormont and the introduction of Direct Rule in 1972. I remember, as Chairman of the Community Relations Commission, bringing a group of academics to meet Reginald Maudling, the Home Secretary, to argue for a significant break in the continuity of Unionist rule. With a poshness which the classicist in Pádraig de Brún might have appreciated, we called for a caesura – the break in the rhythm in the centre of a line in Latin poetry. In discussion with Heath’s advisors at the time, it was clear that their chief fear was of obstruction by the civil service or a police mutiny, or both. Neither happened, largely because of the ingrained culture of political neutrality (however imperfectly understood) which was inbred in the British civil service tradition. In fact they were able to do it again when Direct Rule gave way to a power-sharing local administration and ultimately to the present DUP/Sinn Fein duopoly, the two traditionally most hostile and least co-operative groupings. It is worth pausing here to consider who, if not the public service, kept Northern Ireland going while society was tearing itself apart, while local politicians were side-lined and Direct Rule Ministers focused on security and political developments. They ensured the continuity of services and the semblance of a normal society in the midst of mayhem, and this despite the stress placed on individuals by local and tribal allegiances, peer group pressures and common suffering. In this I am thinking of, and would pay tribute to the wider public service – the health service ancillary workers, paramedics, nurses and medical professionals, treating people regardless of their allegiance or activity, the binmen and firemen, the teachers who provided in the schools an oasis of calm in troubled times, and the junior civil servants who turned up for work despite the UWC strikes which brought down the postSunningdale Executive, the hunger strikes, IRA and Loyalist funerals, road blocks, bombs and intimidation. I would argue that the public service was the glue that kept a fissionable society from disintegration. Continuity is important too because some policies and programmes cannot be completed within the life of a single parliament. Politicians and civil servants march to a different drum beat. The minister’s horizon tends to be the next election the result of which is short term, quick- fire projects which can be carried through from conception to completion in three to five years while the departmental civil servant (very often having seen it all before) tends to take a longer view and to counsel prudence and careful planning and testing of options which tends to irritate the politician in a hurry. There are too some programmes which take years to gestate and carry into effect over the life of several parliaments, and often across regime changes. Foreign affairs are one example, transport and energy policy is another. Strategic planning is the antithesis of politics but somebody must do it. If not the Civil Service, who? 4 The Peace Process is a particular case in point where the continuity of policy was ensured by a small group of Irish civil servants and their counterparts on the British side who maintained informal contacts even when the politicians had their horns locked. These were principally Dermot Nally, who is emerging as a national hero in the Whitaker mould, Sean Donlon, Michael Lillis, Dermot Gallagher, Sean O hUigin and Daithi O Ceallaigh and on the British side people like Robert Armstrong, David Goodall, John Chilcott, Quentin Thomas and Jonathan Stephens. Incidentally Armstrong had been Heath’s Private Secretary at Sunningdale and Nally had worked with Jack Lynch which shows the value of continuity. Progressive releases of papers under the 30 year rule shows the efforts of Nally in pulling the Taoiseach back from impossible positions or reminding all of the issues at stake and radiating a general common sense and calm. Whitaker, too, is seen in the papers, even in semi -retirement intervening with helpful advice to ministers on the economy and crucially on Northern Ireland policy. In all cases they are performing what I regard as a prime function of the senior civil servant in any jurisdiction – to remind the Emperor that he has no clothes. Contrary to popular belief too (formed by too much addictive viewing of Yes, Minister) civil servants prefer a strong minister – you know what he wants, what the policy is, and that he is strong enough politically and in personality to fight his corner in Cabinet, to secure resources from Treasury for Departmental programmes and public support for his policies. If he is not strong enough to stand up to the Civil Service he is unlikely to be able to stand up to others either. IV But back to the causes of the present discontent and their impact on the reputation and standing of the civil service: the banking crisis which was global and the excess of public expenditure over income which was purely domestic and self- inflicted. Both affected the reputation and standing of the public service. In the first case it does seem that some regulators were asleep at their post or not up to the job, and the cult of the generalist took a drubbing when it was disclosed that there was only one trained economist in the Department of Finance and no one with financial or banking experience, and that the poachers had become much smarter than the gamekeepers.. There was too an apparent lack of accountability in which no one was seen to carry the can and as yet no satisfactory narrative of the process and on what advice by which crucial decisions were taken. This paralysis of government in the face of crisis was not confined to Ireland it was part of a pattern in which fashionable ideologies sought to reinvent government by having no government at all, and in which regulation became a dirty word and a loose rein the mantra. A mission statement from the office of the Taoiseach at the time boasted a commitment ‘to 5 question both the necessity and the effectiveness of regulation before doing so’ and a promise of moderate penalties in the case of failure to comply. People who do not see the need for regulation soon neglect to regulate themselves – as in the shameful case of a Department ignoring the law even when the breach has been pointed out by the Ombudsman. It soon became clear that Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand of the market’ was engaged in picking the pockets of the poor and his fears of a conspiracy of professionals against the common good were only too well founded. I also happen to think that the mind-set which declared an end to history, the elimination of risk from financial markets and the ability of untrammelled market forces to ensure both growth and equity without government interference or regulation has left the world in a sorry mess. The loss of historical perspective involved in removing the South Sea Bubble and the Wall Street Crash from the history curriculum erased a race memory of economic cycles and the alternation of boom and bust which goes back to the Pharaohs. Keynes’ most recent biographer, Vincent Barnett, comparing the current financial crisis with the crash of 1929 noted that both started off in the financial and banking centres but quickly spread to many other parts of the ‘real’ economy; both followed a long period of boom in which it was declared that ‘the good times would never end’ or that a ‘ Goldilocks economy’ had been created in which the balance of growth factors was ‘just right’; both involved a ‘flight to cash’ that put severe strain on the price of many capital assets….and both had a seriously dampening effect on overall levels of employment and business confidence. Barnett, has identified the problem for countries like Ireland where successive governments have allowed the accumulation of large budget deficits which means that the capacity to finance the measures necessary to kick start the economy is limited. Governments are thus faced with the contradictory tasks of having to increase expenditure in order to stimulate economic growth while simultaneously trying to cut expenditure in order to bolster their credit worthiness and diminish the interest rates paid on debts. I would describe myself in this field as a time- expired Keynesian who kept his head down for the last thirty years as regulation and intervention in markets went out of fashion, as the monetarists and free market capitalists did their worst. In an old fashioned way too, I take a Micawberish approach to budgeting – of a nation living, as a household, within its means. ‘Annual income £20, annual expenditure 19/19/6, result happiness; annual income £20, annual expenditure £20.06, result misery’. Although it must be said that a gap of 20 billion in the national housekeeping is more than even Wilkins Micawber could contemplate with any degree of equanimity not to mind optimism. 6 In any case, it seems a poor prospectus for managing an economy to so over-borrow to finance a gross failure to live within one’s means that the Germans do it for you The reduction of the fiscal gap is therefore the critical second leg of the dilemma facing the nation, and one that is entirely within our own responsibility and competence to deal with. It is also a problem which deeply involves the public sector, indeed largely originating there. Public sector pay is the largest single element in public expenditure and the rapid escalation arising from bench marking and supine pay settlements in the late 90s and early Noughties has been a large contributor to this deficit. Where public sector pay amounts to 70% of the cost of services it is difficult to secure significant savings (short of a savage curtailment of services) without securing a reduction in the amount and the rates of pay – and yet it seems that it is always the services which are cut first. I don’t think that benchmarking with the private sector (described by one trade union leader as an ATM machine for his members – in other words an immediate source of cash with minimal observable effort) was an appropriate way to determine civil service pay particularly when the comparison omitted such key features as job security and more than index linked pensions – and which seems to have gone out of fashion now that wages are being cut elsewhere. Incidentally since one of the main levers which is actually in the hands of the government is public sector pay, it has always amazed me that this vital element should have been removed from democratic scrutiny and debate by the elected legislature and handed over to the Social Partnership (including such bizarre groups as Superiors of Religious Orders) to determine the direction of economic policy. The social partnership was helpful in its early years in calming industrial conflicts but has become dominated by public sector unions faced by a management side which appeared to roll over like Walter Monkton who settled disputes ‘on their terms of course,” a lack of robustness in negotiation which is reflected in the soft ride being given to medical consultants, to drug companies and to religious orders in relation to compensation for childabuse. Trade Unions are uniquely combinations of people in work with more regard to protect their own pay and privileges than the need of others for jobs, and public sector unions, unlike their industrial counterparts, do not carry the fear that they will price the firm out of business. V We are, I would argue, at a crossroads in pattern and styles of economic governance which presents its own challenge to the public service – what the jargon calls a paradigm 7 shift. Adam Smith and Marx are both seen to have been wrong (if they were ever completely right). The command economy and free market capitalism both have had their day and a new dispensation is required. Crisis, as so often can be grasped as opportunity. It would be a pity if the present attempts to secure public sector reform were to stop at fiddling around at the edges with pay and conditions when deep cultural changes are required and fundamental restructuring. Before we get down to the business of what sort of public service we need, and what we want them to do, it is necessary to clear the decks at governmental level of a great deal of clutter. Apart from the dominance of the Dáil by the Executive, Ireland is probably the most centralised system of government in Europe, local government having been progressively shorn of power, of money, decision making and functions. A real start could be made on decentralisation and devolution while the recreation of a limited number of local or regional authorities based on the main cities, to look after most issues of service delivery. There is no good reason why ministers should be held directly responsible for every unfilled pothole or every un-emptied bedpan. In clearing the decks it might be worth revisiting the analysis and recommendations of the Devlin report in the 1970s which drawing on Swedish models recommended a division between policy making and service delivery functions: the first to be performed by a small Aireacht close to the Minister with service delivery hived off to executive agencies. This far seeing effort to galvanise the bureaucracy and to streamline decision making and service delivery perished on the essentially clientalist nature of Irish politics and the fact that Ministers retain their seats and their constituency roles (unlike France where Cabinet Ministers resign their seats) and regard these as more important than their ministerial functions. This parallels the view of Peter Drucker that any attempt to combine governing with ‘doing’ on the large scale paralyses the decision making capacity – any attempt to have decision making organs actually ‘do’ results in very poor” doing”. They are not focused on ”doin”g they are not equipped for it. All of which is more pithily expressed by Osborne and Gaebler that ‘governments should steer not row’. On which reasoning the decision to bring the HSE into the Department of Health is decidedly perverse. Developments since Devlin too make it much easier to outsource or to privatise many elements of what had become traditional municipal or public services and the provision of alternative and competing suppliers. As Osborne and Gaebler have argued, services can be contracted out, but not governance. They point out that business does some things better than government, and government, in such things as regulation, policy management, ensuring equity and stability does things better than the private sector. Business tends to be better at performing economic tasks and the not-for-profit sector those requiring compassion and human relations. There are advantages too in not having to rely totally on monopoly suppliers who can hold society up to ransom. 8 VI The public service, and it has to be said, particularly at the upper levels, have done themselves no favours, won few friends, by appearing to hang on to pay, pensions and privileges when others in the private sector are losing their jobs or having to tighten their belts to avoid doing so. Underlying all however is the fact that public sector pay has got out of kilter not only with the ability of the economy to afford it but in comparison with other competitor countries. The fact is that the wage bill is too high and that wage rates in the public sector are comparatively too high and will have to be reduced progressively. In most occupations and at most levels Irish rates, if not the highest, are in the top decile of OECD countries often for less demanding levels of activity. Ed Welsh has been banging on about this for years. Public sector rates in the south are more generous than in Northern Ireland – there seems to be no good reason why a medical consultant in Donegal should be paid more than twice the rate of his counterpart in Derry and that is before taking private practice earnings into account. Reducing wages, particularly in a depression, is not an easy task and may have to be achieved by a standstill on wages and increments for a number of years and lower starting salaries for new entrants. A quid pro quo might be a guarantee of no compulsory redundancies – scarcely necessary in a large organisation with considerable staff turnover from people leaving or retiring every year. The situation in Northern Ireland is somewhat different. There rates are generally lower – although there is a strong economic argument for a regional rate of public sector pay which would be lower than the present UK wide rates determined by higher costs of living in the south east of England. The problem in the North is the comparative size of the public sector which dominates the economy and which urgently needs to be reduced. There is a need to get both the pay bill and the rates down. In the short term it is the pay bill which is the more important. It is important too that this is not presented or seen by the recipients as a populist punitive expedition against public servants but as a necessary sacrifice in the great patriotic war against the deficit. The staff in any organisation, especially one as labour intensive as the public service, are its most valuable asset and need to be cherished. People who have dedicated their lives to a service should not be treated like cannon fodder at the Somme to be expended at the whim of Generals and staff officers who are themselves well protected behind the lines. The majority in the service are dedicated committed people who know much more about the job than those who manage. They are at least entitled to stability and to continuity of work, decent management and investment in their personal and professional development. In return for flexibility people can be safely guaranteed employment – not necessarily ‘the’ job but ‘a’ job. VII 9 Having cleared the decks, what is needed for governance is a lean machine much slimmed down, business like non-bureaucratic. Obviously the service of Northcote-Trevlyan is no longer best fitted for the task, even in its home base. A recent report on the Whitehall Service quoted in a leader in the London Times criticised it for being too reliant on the philosophy of the generalist amateur too distrustful of outsides especially those with specific expertise too tolerant of poor management and too likely to be promoted on seniority. Sadly this almost exactly echoes the findings of the Fulton report of 1957 – the mandarins having ignored Di Lampedusa’s advice in The Leopard that “if you want things to stay as they are you have got to make changes.” A modern public service geared to governance with executive and service delivery functions located with local authorities, executive agencies, and non-profit organisations or contracted out would be leaner and flatter, less hierarchical and with multiple points of entry. There would be specialisation and tenure within broad policy areas and much more use of qualified professionals, especially in finance and economics. It would be a younger service with many more women in senior positions and more movement in and out to academia and the business and commercial sector, and much more exposure to the activities they are supposed to regulate. They would be more visible when giving advice and more accountable for it. There would be more protection for whistle-blowers, but relief from the culture of over-audit which substitutes box-ticking for service delivery. They would, however, retain the ethos of the civil service of Whitaker and Nally – integrity, independence and political neutrality. The service will abandon the strict cult of the generalist and the myth of detachment and non-commitment. (I always preferred to have people around me with a bit of fire in their belly, and an enthusiasm to achieve the aims of the policy. Too many now approach the task as if there was no difference between running a hospital or a prison or a transport system) Experts in their field should be full members of the team, not held in reserve to be called in when desired, in the supercilious dogma of Whitehall, “on tap but not on top”. There is a place too for Ministerial advisors, both political and expert, provided that their role is clearly defined and that they too have a code of ethics. The question arises where to find the men and women to staff and run this new-model organisation. Where are the latter-day Whitakers and Nally’s (and the Thekla Beeres – the first, and for a long time, the only female head of a department). For one thing, there is now much more competition for the qualities and talents required, and many more career choices for those for whom in the past the civil service would have been a first choice. Neither does the public service have the status and the kudos it once enjoyed, nor a permanent pensionable job the same attraction, less desire too, as Louis MacNeice put it to “sit on your arse for fifty years and hang your hat on a pension”. 10 There will be some who will make a career of it – and they are important for continuity and for the preservation of the organisational memory (which can never be completely captured on files or in cloud computing) others who will move in and out to broaden their experience and to create networks of contacts with other parts of the economy, and others in for shorter periods to meet specific needs. The important thing is that they move into a culture which though open to challenge and receptive to ideas, maintains the integrity of a commitment to public service, the national interest and the common good. As to getting these people – access should be as open as possible to people with varied experience and backgrounds with entry available at various levels of age, experience and competence. It may be necessary to head-hunt or to grow talent (Whitakers do not grow on trees) which may require a more imaginative approach to recruitment, and to invest heavily in personal and staff development. There is a lot to be said for the French enarque system – les Grandes Ecoles – a nod perhaps to an academic institute or business school that there is an openingthere for enterprise, a need to create an institute for training and research in public administration and governance, a forum for the exchange of ideas and experiences and the maintenance of an informed public debate on issues of public policy. I don’t think I ever met a civil servant, North or South, who was in it for the money, yet, in a competitive world where skills are short and labour at this level highly mobile, it is necessary to have a sensible pay policy, determined by the need to attract, recruit, retain and motivate high quality staff. It should also reflect the values of the wider society so as to avoid the impression of a privileged and pampered elite. That said, some skills are scarcer than others, and for some posts and some specialisms it will be necessary to fish in international waters where the best can be attracted not only by money but by better facilities, more exciting colleagues, better working conditions and higher levels of peer group recognition – intangibles which it will be a challenge for a small national service to meet. In these special circumstances it would be counter-productive as well as puritanical parsimony which ordained that no one should be paid more than a small proportion above the average. The HSE spends €13bn a year – if you could find the person to run it, it would be worth paying over the odds – which begs the larger question whether in its present form the HSE is capable of being run by anyone.. I would pay maths and science teachers a substantial premium because of the importance of these subjects to the economy. If it is not pay or permanence or pension, how are civil servants to be recruited and motivated. The British did it by a somewhat tattered and increasingly discredited honours system where the gong came up with the rations depending on the grade. Neither is a bonus entirely appropriate where team effort is required and the personal pursuit of bonus can have perverse results. Career enhancement and personal development is one possibility, easy mobility from public to private sector, to finance and industry, to voluntary bodies and the not for profit sector, and, crucially to academic work and research, and a 11 recognition in terms of future employability of the diverse experience gained. And then there are still patriotic and public-spirited young people who will do the job for the satisfaction they get out of it as much as for what they can put in. It will help if they have public recognition and the respect of their political masters, and while properly being held to account and to a high level of performance, are not scapegoated for failure and inadequacy at the political level. Indeed the importance of political leadership cannot be over-emphasised. People like Sean Lemass and Garrett Fitzgerald can inspire and embolden those who work for them, and can make the work of government attractive to young idealistic people for whom the challenge is more important than the money. So, with the decks cleared, the ship re-rigged, with a young and multi-talented crew and modern navigational aids, we might put to sea again, imbued with enthusiasm and patriotic purpose, holding on to old values if not old methods, like the sailors in Louis MacNeice’s great poem Thalassa: Put out to sea, ignoble comrades Whose record shall be noble yet… By a high star our course is set. Our end is life. Put out to sea. God grant them a skipper who knows where he wants to go, and a navigator who knows how to get there. ENDS 12