StatPascal

User Manual and Reference

R.-D. Reiss

M. Thomas

Xtremes Group

Zur Alten Burg 29

57076 Siegen

Germany

2

Inquiries

Please e-mail all inquiries and bug reports to

info@xtremes.de

Check the Xtremes homepage for the latest information:

http://www.xtremes.de

Copyright Notice

Copyright (C) 1997, 2002, 2005 by Xtremes Group, Siegen. All rights reserved.

Disclaimer

Xtremes Group does not offer any representations or warranties for Xtremes Group

products with respect to their performance or fitness for a particular purpose.

Xtremes Group believes that the information contained in this manual is correct.

However, Xtremes Group reserves the right to revise the product hereof and make

any changes to the contents without the obligation to notify any user of this

revision. Xtremes Group does not assume the responsibility for the use of this

manual, nor the product described therein.

Contents

1 Introduction to StatPascal

1.1 StatPascal integrated in Xtremes . .

1.1.1 The ‘Hello, World” Program

1.1.2 The StatPascal Window . . .

1.1.3 A second Example Program .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

11

12

12

12

13

2 Programming with StatPascal

2.1 Basic Programming . . . . . . . . . .

2.1.1 Variables and Data Types . .

2.1.2 Expressions and Assignments

2.1.3 Constant Declarations . . . .

2.1.4 Input and Output . . . . . .

2.1.5 Conditional statements . . .

2.1.5.1 if-statement . . . . .

2.1.5.2 case-statement . . .

2.1.6 Loops . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.1.6.1 while-loop . . . . .

2.1.6.2 repeat-loop . . . .

2.1.6.3 for-loop . . . . . . .

2.1.7 Procedures and Functions . .

2.1.8 Forward Declarations . . . .

2.2 Data Structures and Types . . . . .

2.2.1 Arrays . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.2.2 Type declarations . . . . . .

2.2.3 Ordinal types . . . . . . . . .

2.2.3.1 Enumerations . . .

2.2.3.2 Subranges . . . . . .

2.2.4 Records . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.2.5 Sets . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.2.6 Pointers . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

15

15

15

16

17

18

19

19

20

20

20

21

21

22

24

25

25

26

27

27

28

28

29

30

3

4

3 Vector and Matrix Operations

3.1 Introductory Examples . . . .

3.2 Construction of Vectors . . .

3.3 Type Conversions . . . . . . .

3.4 Assignments . . . . . . . . . .

3.5 Output . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.6 Expressions . . . . . . . . . .

3.7 Index Operations . . . . . . .

3.8 Function Calls . . . . . . . .

3.9 Special Operations . . . . . .

3.10 Strings . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.11 Matrix Operations . . . . . .

CONTENTS

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

31

31

33

33

34

34

35

35

36

36

37

37

4 Advanced StatPascal Techniques

4.1 Units . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.2 Functional and Procedural Types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.3 Evaluation of Boolean Operands . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.4 Generating and Accessing Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.4.1 Passing Data from StatPascal to Xtremes . . . . . . .

4.4.2 Passing Data from Xtremes to StatPascal . . . . . . .

4.4.3 Temporary Data Sets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.5 Predefined Estimators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.6 Estimator Programs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.6.1 Implementing Estimators of the Shape Parameter . .

4.6.2 Implementing Estimators of Further Parameters . . .

4.7 StatPascal Runtime Environment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.7.1 Handling Run–Time Errors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.7.2 The Compile Button in the StatPascal Editor . . . . .

4.7.3 The Compiler Options Button . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.8 Appending StatPascal Programs to the Menu Bar of Xtremes

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

39

39

41

41

42

42

44

44

45

47

47

49

49

49

50

51

52

5 Input and Output

5.1 The StatPascal Window . . . . . .

5.2 File Operations . . . . . . . . . . .

5.2.1 Text Files . . . . . . . . . .

5.2.2 Binary files . . . . . . . . .

5.3 Plots . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5.3.1 Univariate Curves . . . . .

5.3.2 Scatterplots . . . . . . . . .

5.3.3 Contour and Surface Plots .

5.3.4 Polygons . . . . . . . . . .

5.3.5 Overview Of Advanced Plot

5.4 Graphical User Interface . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

53

53

53

53

54

55

55

55

55

56

56

57

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Options

. . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

CONTENTS

6 Syntax of StatPascal

6.1 Lexical Elements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.1.1 Special Symbols and Reserved Words . .

6.1.2 Identifiers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.1.3 Numerical Constants . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.1.4 Character and String Constants . . . . . .

6.1.5 Comments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.2 Blocks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.3 Labels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.4 Constants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.5 Types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.5.1 Type Declarations . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.5.2 Simple Types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.5.2.1 Ordinal Types . . . . . . . . . .

6.5.2.2 Reals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.5.3 Structured Data Types . . . . . . . . . .

6.5.3.1 Sets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.5.3.2 Arrays . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.5.3.3 Vectors . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.5.3.4 Matrices . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.5.3.5 Records . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.5.3.6 Pointers . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.5.3.7 Procedural and functional types

6.5.4 Compatible Types . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.6 Variables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.6.1 Variable Declarations . . . . . . . . . . .

6.6.2 Accessing Variables . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.6.2.1 Arrays . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.6.2.2 Records . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.6.2.3 Pointers . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.6.2.4 Syntax . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.7 Expressions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.7.1 Syntax . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.7.2 Operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.7.2.1 Arithmetic operators . . . . . .

6.7.2.2 Logical operators . . . . . . . . .

6.7.2.3 Relational operators . . . . . . .

6.7.2.4 String operators . . . . . . . . .

6.7.3 Function Calls . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.8 Statements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.8.1 Compound Statements . . . . . . . . . . .

6.8.2 Simple Statements . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.8.3 Return Statement . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.8.4 Memory Allocation . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

59

59

59

60

60

61

61

62

63

64

64

65

66

66

66

67

67

67

67

67

68

68

68

68

69

69

70

70

70

71

71

71

71

73

73

74

74

74

74

74

75

75

76

76

6

CONTENTS

6.8.5

6.8.6

Goto Statement . . . . .

Iterations . . . . . . . .

6.8.6.1 while-Loop . .

6.8.6.2 repeat-Loop .

6.8.6.3 for-Loop . . .

6.8.7 Selections . . . . . . . .

6.8.7.1 if-Statement .

6.8.7.2 case-Statement

6.9 Procedures and Functions . . .

6.10 Units . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.11 Programs . . . . . . . . . . . .

7 The

7.1

7.2

7.3

7.4

7.5

7.6

7.7

7.8

7.9

7.10

7.11

7.12

7.13

7.14

7.15

7.16

7.17

7.18

7.19

7.20

7.21

7.22

7.23

7.24

7.25

7.26

7.27

7.28

7.29

7.30

7.31

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

76

76

76

77

77

77

77

78

78

79

80

StatPascal Library Functions

abs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

All . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

arccos . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

arcsin . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

arctan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

BetaData . . . . . . . . . . . . .

BetaDensity . . . . . . . . . . . .

BetaDF . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

BetaQF . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

BeginMultivariate . . . . . . . .

BinomialData . . . . . . . . . . .

BoxPlot . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

CBind . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ChiSquareData . . . . . . . . . .

ChiSquareDensity . . . . . . . . .

ChiSquareDF . . . . . . . . . . .

ChiSquareQF . . . . . . . . . . .

Chol . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Choose . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

chr . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ClearWindow . . . . . . . . . . .

ColumnData . . . . . . . . . . .

ColumnName . . . . . . . . . . .

cos . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

cosh . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

CreateMultivariate . . . . . . . .

CreateTimeSeries . . . . . . . . .

CreateUnivariate . . . . . . . . .

CumSum . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

DataType . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

83

84

84

84

85

85

85

86

86

86

87

87

87

87

88

88

88

89

89

89

90

90

90

90

91

91

91

92

92

93

93

93

CONTENTS

7.32

7.33

7.34

7.35

7.36

7.37

7.38

7.39

7.40

7.41

7.42

7.43

7.44

7.45

7.46

7.47

7.48

7.49

7.50

7.51

7.52

7.53

7.54

7.55

7.56

7.57

7.58

7.59

7.60

7.61

7.62

7.63

7.64

7.65

7.66

7.67

7.68

7.69

7.70

7.71

7.72

7.73

7.74

7.75

Date . . . . . . . . .

DialogBox . . . . . .

Dimension . . . . . .

DreesPickandsGP . .

EndMultivariate . .

eof . . . . . . . . . .

EstimateBandwidth

EVData . . . . . . .

EVDensity . . . . .

EVDF . . . . . . . .

EVQF . . . . . . . .

Exists . . . . . . . .

exp . . . . . . . . . .

ExponentialData . .

ExponentialDensity .

ExponentialDF . . .

ExponentialQF . . .

Extremes . . . . . .

Flush . . . . . . . .

frac . . . . . . . . . .

FrechetData . . . . .

FrechetDensity . . .

FrechetDF . . . . . .

FrechetQF . . . . . .

gamma . . . . . . . .

GammaData . . . .

GammaDensity . . .

GammaDF . . . . .

GaussianData . . . .

GaussianDensity . .

GaussianDF . . . . .

GaussianQF . . . . .

GCauchyData . . . .

GCauchyDensity . .

GCauchyDF . . . . .

GCauchyQF . . . . .

GeometricData . . .

GMFEVDF . . . . .

GMFEVDensity . .

GMFEVSF . . . . .

GMFGPDF . . . . .

GMFGPDensity . .

GMFGPSF . . . . .

GotoXY . . . . . . .

7

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

94

94

95

95

95

96

96

97

97

97

97

97

98

98

98

99

99

99

99

99

100

100

100

100

100

101

101

101

101

101

102

102

102

102

102

103

103

103

103

103

104

104

104

104

8

CONTENTS

7.76 GPData . . . . .

7.77 GPDensity . . .

7.78 GPDF . . . . . .

7.79 GPQF . . . . . .

7.80 GumbelData . .

7.81 GumbelDensity .

7.82 GumbelDF . . .

7.83 GumbelQF . . .

7.84 HillGP1 . . . . .

7.85 HREVDF . . . .

7.86 HREVDensity . .

7.87 HREVSF . . . .

7.88 HRGPDF . . . .

7.89 HRGPDensity . .

7.90 HRGPSF . . . .

7.91 Indicator . . . . .

7.92 Invert . . . . . .

7.93 KernelDensity . .

7.94 log . . . . . . . .

7.95 ln . . . . . . . . .

7.96 LRSEV . . . . .

7.97 MakeMatrix . . .

7.98 max . . . . . . .

7.99 MDEEV . . . . .

7.100MDEGaussian .

7.101Mean . . . . . . .

7.102Median . . . . .

7.103MEGP1 . . . . .

7.104MemAvail . . . .

7.105MenuBox . . . .

7.106MessageBox . . .

7.107MHDEGaussian .

7.108min . . . . . . .

7.109MLEEV . . . . .

7.110MLEEV0 . . . .

7.111MLEEV1 . . . .

7.112MLEGaussian . .

7.113MLEGP . . . . .

7.114MLEGP0 . . . .

7.115Moment . . . . .

7.116MomentGP . . .

7.117NegBinData . . .

7.118ord . . . . . . . .

7.119Page . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

105

105

105

105

105

106

106

106

106

107

107

107

107

108

108

108

108

108

109

109

109

110

110

110

111

111

111

111

112

112

113

113

113

114

114

114

115

115

116

116

116

117

117

117

CONTENTS

7.120ParamCount . . . . . .

7.121ParamStr . . . . . . . .

7.122ParetoData . . . . . . .

7.123ParetoDensity . . . . . .

7.124ParetoDF . . . . . . . .

7.125ParetoQF . . . . . . . .

7.126Plot . . . . . . . . . . .

7.127PlotContour . . . . . . .

7.128PlotSurface . . . . . . .

7.129PoissonData . . . . . . .

7.130Poly . . . . . . . . . . .

7.131PolynomialRegression .

7.132pred . . . . . . . . . . .

7.133Random . . . . . . . . .

7.134Rank . . . . . . . . . . .

7.135RBind . . . . . . . . . .

7.136read . . . . . . . . . . .

7.137ReadData . . . . . . . .

7.138readln . . . . . . . . . .

7.139RealVect . . . . . . . . .

7.140Rev . . . . . . . . . . .

7.141RGB . . . . . . . . . . .

7.142round . . . . . . . . . .

7.143RowData . . . . . . . .

7.144SampleDF . . . . . . . .

7.145SampleMeanClusterSize

7.146SampleQF . . . . . . . .

7.147SampleSize . . . . . . .

7.148SaveEPS . . . . . . . . .

7.149ScatterPlot . . . . . . .

7.150SetColor . . . . . . . . .

7.151SetColumn . . . . . . .

7.152SetCoordinates . . . . .

7.153SetLabel . . . . . . . . .

7.154SetLabelFont . . . . . .

7.155SetLineOptions . . . . .

7.156SetLineStyle . . . . . . .

7.157SetMarkers . . . . . . .

7.158SetMarkerFont . . . . .

7.159SetPlotStyle . . . . . . .

7.160SetPointStyle . . . . . .

7.161SetTicks . . . . . . . . .

7.162sign . . . . . . . . . . .

7.163SimulateRuinTime . . .

9

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

117

118

118

118

118

119

119

119

119

120

120

120

120

121

121

121

121

122

122

123

123

123

123

124

124

124

124

125

125

126

126

126

127

127

127

128

128

128

128

129

129

130

130

130

10

CONTENTS

7.164sin . . . . . . . . . . .

7.165sinh . . . . . . . . . .

7.166size . . . . . . . . . . .

7.167Smooth . . . . . . . .

7.168Sort . . . . . . . . . .

7.169sqr . . . . . . . . . . .

7.170sqrt . . . . . . . . . .

7.171str . . . . . . . . . . .

7.172StratifiedUniform . . .

7.173succ . . . . . . . . . .

7.174sum . . . . . . . . . .

7.175system . . . . . . . . .

7.176tan . . . . . . . . . . .

7.177tanh . . . . . . . . . .

7.178TData . . . . . . . . .

7.179TDensity . . . . . . .

7.180TDF . . . . . . . . . .

7.181TextBackground . . .

7.182TextColor . . . . . . .

7.183Time . . . . . . . . . .

7.184TQF . . . . . . . . . .

7.185Transpose . . . . . . .

7.186TTest . . . . . . . . .

7.187UFODefine . . . . . .

7.188UFOMessage . . . . .

7.189UFOEvaluate . . . . .

7.190UniformData . . . . .

7.191UnitMatrix . . . . . .

7.192UnitVector . . . . . .

7.193Variance . . . . . . . .

7.194WeibullData . . . . . .

7.195WeibullDensity . . . .

7.196WeibullDF . . . . . . .

7.197WeibullQF . . . . . .

7.198WelchTest . . . . . . .

7.199WilcoxonTest . . . . .

7.200write . . . . . . . . . .

7.201writeln . . . . . . . . .

7.202Estimator Error codes

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

130

131

131

131

132

132

132

132

132

133

133

133

133

134

134

134

134

135

135

135

135

136

136

136

136

137

137

137

138

138

138

138

139

139

139

139

139

140

141

A Porting to StatPascal

143

A.1 Differences between StatPascal and Pascal . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143

A.2 Differences to XPL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 144

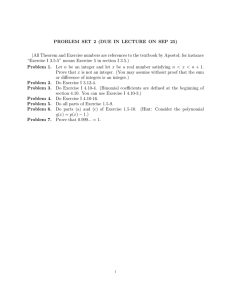

Chapter 1

Introduction to StatPascal

StatPascal is a statistical programming language that is based on the Pascal language. It is available within the menu system of Xtremes and as a text-oriented

commmand line language that runs on Win32 and Unix platforms. StatPascal

provides the following extension to standard Pascal that are important within a

statistical context.

• Vector and matrix operations,

• a library with statistical routines,

• predefined plots and some simple GUI elements.

In contrast to other statistical languages, StatPascal is strongly typed and

employes a compiler to produce code for an abstract stack machine. The resulting

runtime performance is usually better than the one achieved with an interpreted

system.

StatPascal supports most of the features of the Pascal language to ease porting existing algorithms to StatPascal. However, StatPascal lacks the following facilities of Pascal:

• variant records

• with statements

• Pascal–like file access

The first two gaps may be filled in future releases, while the file access is based on

the concepts provided by the C language.

This chapter describes the first steps with StatPascal. We start with a description of the integrated StatPascal editor within Xtremes and demonstrate some

introductory example programs.

The following typographie is used.

11

12

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO STATPASCAL

Boldface reserved words within text

Italics identifiers within text

Typewriter program listings

Function names specific to StatPascal are written utilizing both lower and upper

case letters (e.g. GaussianDensity), while functions also available in common programming languages are presented using only lower case letters. StatPascal is not

case sensitive, so you can use upper and lower case letters within a StatPascal

program.

1.1

StatPascal integrated in Xtremes

A StatPascal editor window is opened by selecting the

button within the

toolbar. Please note that under Windows 98, the maximum file size of the editor

window is limited to 64 KBytes.

The toolbar enables the user to save and load text files. The Run option

is a short cut for the compilation and execution of a program. Table 1.1 lists the

available tools.

1.1.1

The ‘Hello, World” Program

We start with the traditional ‘Hello, world” program to demonstrate the techniques of entering, compiling and running a StatPascal program. The user will

immediately recognize that the program looks like its Pascal equivalent.

program hello;

begin

writeln (’Hello, world!’)

end.

Type in the program, save it to a file (Save as,

and click the Run button

to execute the program. If the program contains no errors, Xtremes opens

the StatPascal window displaying the output.

1.1.2

The StatPascal Window

The procedures write, writeln and read of the Pascal language are provided to