Negotiation

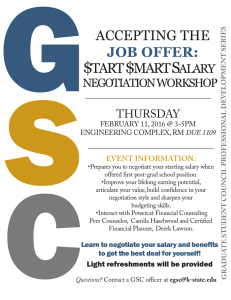

advertisement

Updated September 2011 Negotiation Virginia Valian Hunter College and CUNY Graduate Center, New York, NY at least moderate feelings of entitlement are necessary to negotiate effectively o understand how entitlement works and how it interacts with gender o women and men differ in how entitled they feel and behave women perform equal or better work for less pay women ask for less o women have negative attitudes toward affirmative action for themselves women chosen on the basis of their sex have more negative selfevaluations than do men chosen on the basis of their sex o women and men may differ in attributions for success and failure o women deny personal disadvantage negotiation is a skill that can be learned o negotiations have 3 parts: preparing for it, conducting it, and concluding it see details in Williams and Valian (2003) o preparing: know what you want and what you are prepared to give up; consider what is likely to matter to the person you're negotiating with; practice negotiating with someone else before the event; consider the power differences between you and the person you'll be negotiating with o conducting: be pleasant and neutral throughout; listen carefully and sympathetically to the other person's concerns without forgoing your own interests; search for common interests; compromise when necessary and do so pleasantly o concluding: end politely and gracefully both men and women react more negatively to women who negotiate than to men who negotiate, and women who are perceived as self-aggrandizing are viewed particularly negatively, so success for women requires demonstrating larger benefits o example: you want an assistant; show how that assistant will make you or your section more productive and allow you to add a needed function or improve an existing function o example: you want a course release or other time release; show that you will use the time to apply for a grant in a new area or embark on some other new activity that will benefit the institution o example: you want a course release in order to be an NIH grant panelist; when asking, say that you will provide grant writing workshops to faculty o example: you want a considerable salary increase; justify it by a) what the going rate seems to be b) the extra responsibilities you have assumed c) the benefits you have recently brought to the institution d) the initiatives that you are planning on undertaking Negotiation; Virginia Valian, September 2011 2 negotiate on the basis of what the job needs more than what you need (it's not that you in particular need help but that the job has a certain set of requirements) o example: the job (chairing a committee) requires a part-time person to handle a particular set of tasks; briefly detail tasks and time; ideally, have a person in mind if feasible, offer to share the expenses for an item you are requesting everything can be negotiated: o salary o resources o teaching number of courses level of course labor-intensiveness of course teaching assistance ability to teach in one's area o travel funds o extra compensation for performing extra institutional work research assistants summer salary course reduction support for postdoc support for graduate student equipment extra term off early sabbatical women negotiate effectively for other people; the skills are there practice negotiating in low-stress situations, such as shopping Negotiation; Virginia Valian, September 2011 3 Partial Annotated References Babcock, L. & Laschever, S. (2003). Women don't ask: Negotiation and the gender divide. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. One reason women do not do as well as men is that women attempt to negotiate in fewer areas than men do. Another reason is that organizations are more likely to respond well to men's attempts to negotiate than to women's, especially if women use a "masculine" negotiating style. But also see the next reference. Bowles, H. R., Babcock, L., & Lai, L. (2007). Social incentives for gender differences in the propensity to initiate negotiations: Sometimes it does hurt to ask. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 103, 84–103. Both males and females have a tendency to view people who negotiate for a higher salary more negatively than they perceive people who do not negotiate, but people see women who negotiate much more negatively than they see men who negotiate. In Experiment 1, participants read a fictitious resumé and fictitious interview notes for someone supposedly interviewing for a job as an intern. In one condition, the interview notes indicated that the applicant had asked about a higher salary and about other benefits. Participants were asked to imagine that they were a bank manager and to make a judgment about how hireable a candidate was. Names were gender-neutral; only the interview notes referred to the candidate's sex. The sexes were seen as equally hireable when neither asked for more money, but women's hireability score plummeted (from 6.19 to 4.63 on a scale from 1-7) and men's significantly decreased but less (from 5.94 to 5.26) when the interview notes indicated they had asked for more salary. In a variant, there were no negative effects when men asked but there were negative reactions when women asked. In all variants there were no differences between male and female evaluators' dislike of women who asked for more money, but in one variant, men and women differed in how they treated men, with only women seeing men who asked for money negatively. Chatterjee, K. (1996). Game theory and the practice of bargaining. Group Decision and Negotiation, 5, 355-369. Fershtman, C. (1990). The importance of the agenda in bargaining. Games and Economic Behavior, 2, 224-238. Handley, C. (2003). The art of negotiation. iVillage.co.uk. http://www.ivillage.co.uk/workcareer/survive/prodskills/articles/0,,156472_16544 0,00.html. Retrieved 10/2010. Kolb, D. M. & Williams, J. (2003). Everyday negotiation: Navigating the hidden agendas in bargaining. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Patterson, K., Grenny, J., McMillan, R., Switzler, A., & Covey, S. R. (2002). Crucial conversations: Tools for talking when stakes are high. New York: McGraw-Hill. Ridgeway, C. L. (1982). Status in groups: The importance of motivation. American Sociological Review, 47, 76-88. Negotiation; Virginia Valian, September 2011 4 To be accepted as a leader, both men and women must demonstrate their competence to the group, but women in addition must demonstrate that they are not trying to acquire status at the expense of other members of the group. Women must subordinate, and be seen to subordinate, their personal needs to the needs of the group. Attempts at self-aggrandizement by women are particularly negatively perceived. Implications: women should be impersonal, friendly, and respectful. Rose, S., & Danner, M. J. E. (1998). Money matters: The art of negotiation for women faculty. In L. H. Collins, J. C. Chrisler, & K. Quina (Eds.), Career strategies for women in academe: Arming Athena (pp. 157-186). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Tips on what to negotiate for and how to negotiate. Examples of what new hires can negotiate about: base salary; moving expenses; rank; office size and location; start-up money; research space; assistants; summer supplements for teaching or research; equipment; conference or research travel expenses; reduced teaching load; lower number of preparations; teaching schedule. Examples of what more advanced faculty can negotiate for: salary increase; promotion to full professor or appointment to named chair; funding for start up of new research; funds to build a program, including faculty lines; funding or fellowships for graduate students; funding for colloquium series; increased space; reousrces for journal editing; new building or renovations of current space. Examples of tips: set goals; conduct the negotiation in person, if possible; let other party name first salary figure; remember that almost everything is negotiable, regardless of the "rule"; be self-confident; use persuasive arguments (for women, it is especially important to avoid appearing self-aggrandizing); approach negotiation as a win-win event; be prepared to trade off. Small, D. A., Gelfand, M., Babcock, L., & Gettman, H. (2007). Who goes to the bargaining table? The influence of gender and framing on the initiation of negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 600-613. Women are more comfortable with negotiation if it is framed in terms of "asking" rather than "negotiating". But if women are primed with a memory of having been powerful in a situation, they find "negotiating" less aversive. Stuhlmacher, A. F. & Walters, A. E. (1999). Gender differences in negotiation outcome: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 52, 653-677. Walters, A. E., Stuhlmacher, A. F., & Meyer, I. I. (1998). Gender and negotiator competitiveness: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 76, 1-29. Kary, L. J., Thompson, L., & Galinksy, A. (2001). Battle of the sexes: Gender stereotype confirmation and reactance in negotiations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 942-958. Men are more competitive and more successful than women in negotiations. One determinant of negotiation success is the 'opening bid'; men tend to make more extreme opening bids than women. In a laboratory simulation of mixed-sex purchase negotiations, ambitious women did worse when their gender stereotypes were implicitly activated and better when they were explicitly activated (leading to reactance). Negotiation; Virginia Valian, September 2011 5 Valian, V. (1998). Why so slow? The advancement of women. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Chapter 14. This chapter summarizes data on personal style and personal effectiveness, but warns that women can do everything "right" and still not advance because of structural problems within the institution. Suggestions: build power, use a "neutral" style in professional settings, become an expert, negotiate, bargain, seek promotion, seek challenging assignments, seek information. Williams, N. & Valian, V. (2003). Tips for effective negotiating. Unpublished manuscript, Hunter College Gender Equity Project. Retrieved 10/2010 from http://www.hunter.cuny.edu/genderequity/WSJFWorkshops/Williams&Valian2003.pdf