Document 14683077

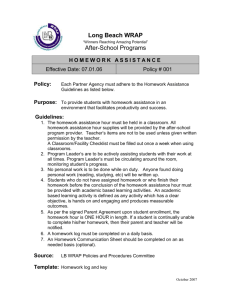

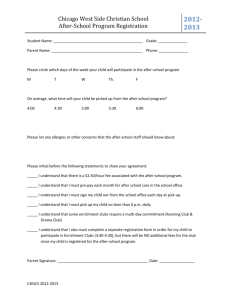

advertisement