ORAL HISTORY OF JAMES INGO FREED Interviewed by Betty J. Blum

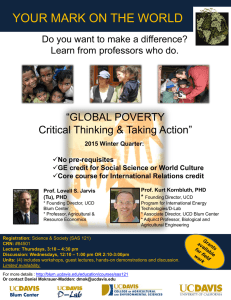

advertisement