Document 14671027

advertisement

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

1

Design and Analysis of Piezoelectric Smart Beam for Active

Vibration Control

Deepak Chhabra1, Kapil Narwal2*, Pardeep Singh3

University Institute of Engineering and Technology, Maharshi Dayanand University, Rohtak, India

Email: 1deepaknit10@gmail.com, 2*mr.k.narwal@gmail.com, 3pardeeppapr@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This paper deals with the Active Vibration control of beam like structures with distributed piezoelectric actuator and sensor

layers bonded on top and bottom surfaces of the beam. The patches are located at the different positions to determine the better

control effect. The piezoelectric patches are placed on the free end, middle end and fixed end. The study is demonstrated

through simulation in MATLAB for various controllers like Proportional Controller by Output Feedback, Proportional Integral

Derivative controller (PID) and Pole Placement technique. A smart cantilever beam is modeled with SISO system. The entire

structure is modeled using the concept of piezoelectric theory, Euler-Bernoulli beam theory, Finite Element Method (FEM) and

the State Space techniques. The numerical simulation shows that the sufficient vibration control can be achieved by the proposed method.

Keywords : Smart Structure, Finite Element model, State Space model, Proportional Output feedback, PID, Pole Placement

1 INTRODUCTION

T

he development of high strength to weight ratio of mechanical structures are attracting engineers to build light

weight aerospace structures as well as to build tall buildings and long bridges. The development of piezoelectric material has been used as sensors and actuators because if the

forces are applied on that material it produces voltage and this

voltage goes to active devices and controls the vibration. Their

reliability, nearly linear response with applied voltage and

their low cost make piezoelectric materials the most widely

preferred one as collocated sensor and actuator pair. Active

vibration control is the active application of force in an equal

and opposite fashion to the forces imposed by external vibration. The finite element method is powerful tool for designing

and analyzing smart structures. A design method is proposed

by incorporating control laws such as Proportional Output

Feedback (POF) and Proprotional Integral Derivative (PID)

and Pole Placement technique to suppress the vibration. Baz

and Poh [2] investigated methods to optimize the location of

piezoelectric actuators on beams to minimize the vibration

amplitudes. Suleman [15] proposed the effectiveness of the

piezo-ceramic sensor and actuators on the attentuation of vibrations on an experimental wing due to the gust loading. Brij

N Agrawal and Kirk E Treanor [6] presented the analytical

and experimental results on optimal placement of Piezoceramics actuators for shape control of beam structures. Manning,

Plummer & Levesley [11] presented a smart structure vibration control scheme using system identification and pole

placement technique. Kapil Narwal and Deepak Chhabra [8]

presented a detailed analysis insight on the active vibration

control of structures. Raja, S, prathap G & Sihna [14] studied

active vibration control of a composite sandwich beam with

two kinds of piezoelectric actuator or such as extensionbending and shear. Xu & Koko [18] proposed results by using

the commercial FE-package and ANSYS. Baillargeon & Vel [1]

presented vibration suppression of adaptive sandwich cantilever beam using PZT shear actuators by experiments and

numerical simulations. T. C. Manjunath & B. Bandyopadhyay

[17] presented the modeling and design of a multiple output

feedback based discrete sliding mode control scheme application for the vibration control of a smart cantilver beam of three

four and five elements. N.S. Viliani1, S.M.R. Khalili [12] studied the active buckling control of smart functionally graded

(FG) plates using piezoelectric sensor/actuator patches. M.

Yaqoob Yasin, Nazeer Ahmad [10] presented the active vibration control of smart plate equipped with patched piezoelectric sensors and actuators. In most of present researches, FEM

formulation of smart cantilever beam is usually done by ANSYS and by design of control laws are carried out in MATLAB toolbox. The objective of this work is to design and

analysis of piezoelectric smart structures with control laws.

Proportional Output Feedback (POF) Controller, Proportional

Integral Derivative (PID) control law and Pole Placement

Technique is used to suppress the vibrations. The eigenvalues

of the closed loop system are also controlled with Pole Placement Technique. Numerical examples are presented to demonstrate the validity of the proposed design scheme. This paper has organized in to three parts, FEM formulation of piezoelectric smart structure with control laws, Numerical simulation and Conclusion.

2 MODELING OF SMART CANTILEVER BEAM

2.1 Finite Element Formulation of Beam Element

A beam element is considered with two nodes at its end.

Each node is having two degree of freedom (DOF) i.e.

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

1

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

translation and rotation is considered. The shape functions

of the element are derived by applying boundary conditions. The mass and stiffness matrix is derived using shape

functions for the beam element. To obtain the mass and

stiffness matrix of smart beam element which consists of

two piezoelectric materials and a beam element, are added.

The global mass and stiffness matrix is formed. The boundary conditions are applied on the global matrices for the

cantilever beam. The first two rows and two columns

should be deleted as one end of the cantilever beam is

fixed. The actual response of the system i.e. the tip displacement is obtained for all the various models of the cantilever beam with and without the controllers.

éf1 (x)ù= éê1- 3x 2 / lb2 + 2 x3 / lb3 ù

ú

ë

û ë

û

2

[n]= éëf 2 (x)ùû= [ x - 2 x / lb + x3 / lb2 ]

(1)

éf3 (x)ù= [3x 2 / lb2 - 2 x3 / lb3 ]

ë

û

éf 4 (x)ù= - x 2 / lb + x3 / lb2 ]

ë

û

(3)

2

2.2 Beam with Piezoelectric at Different Positions

Fig1. Piezoelectric placed at the free end

(2)

(4)

Fig2. Piezoelectric placed at the middle

Where (n) gives the shape functions.

The equation of motion of the regular beam element is obtained by the lagrangian equation

é ù

d éê¶ T ù

ú+ ê¶ U ú= [Fi ]

ê ú

dt êë¶ qi ú

û ë¶ qi û b

b

b

as M q + K q = f (t )

b

b

(5)

(6)

b

Where M , K and F are the mass, stiffness and force

co-efficient vector matrices respectively of the regular beam

element. The mass and stiffness matrices are obtained as

é 156

22lb

54

- 13lb ù

ê

ú

2

ê

22lb

4lb

13lb

- 3lb2 ú

r

A

l

b

b

b

b

ê

ú

éM ù=

ê

ú ò 420 ê 54

ë

û

13lb

156

- 22lb ú

ê

ú

2

2

ê- 13l

ú

3

l

22

l

4

l

b

b

b

b

ë

û

é 12

ê 2

ê lb

ê

ê 6

ê

l

Eb I b ê

ê b

Kb =

lb ê

ê 12

ê l2

ê b

ê 6

ê

ê l

ê

ë b

6

lb

- 12

lb2

4

- 6

lb

- 6

lb

12

lb2

2

- 6

lb

6 ù

ú

lb ú

ú

ú

2 ú

ú

ú

- 6ú

ú

lb ú

ú

ú

4 ú

ú

ú

û

The equation of motion of the smart structure is finally

given by

Mq + Kq = fent + fcntrl = ft

(7)

Fig3. Piezoelectric placed at the fixed end

2.3 Sensor Equation

The total charge Q(t) developed on the sensor surface is the

spatial summation of all the point charges developed on the

sensor layer. Thus, the expression for the current generated is

obtained as

dQ (t ) d

i (t ) =

=

dt

dt

lp

òe

e dA = ze31b ò n1T qdx,

31 x

A

(8)

0

tb

+ ta

2

This current is converted into the open circuit sensor voltage

Vs using a signal-conditioning device with the gain Gc. The

sensor output voltage is obtained as

where

z=

lp

V (t ) = Gce31 zb ò n1T qdx,

s

(9)

0

This Where d31 is the piezoelectric constant, e31 is the piezoelectric stress / charge constant, Ep is the young’s modulus

and x is the strain that is produced.

t

Where M , K , q, f ent , f cntrl , f is the global mass matrix,

global stiffness matrix of the smart beam, the vector of displacements and slopes, and the external force applied to the

beam, the controlling force from the actuator and the total

force vector respectively.

2.4 Actuator Equation

The actuator strain is derived from the converse piezoelectric

equation. The strain developed ea on the actuator layer is

given by

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

2

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

ea = d31E f

(10)

Where, d31 and Ef are the piezo strain constant and the electric

field respectively. When the input to the piezoelectric actuator

V a t is applied in the thickness adirection ta, the electric field,

Ef which is the voltage applied V t divided by the hickness

of the actuator ta and the stress, s a which is the actuator strain

multiplied by the young’s modulus Ep of the piezo actuator

layer are given by

()

()

V a (t )

Ef =

ta

Finally, the control force applied by the actuator is obtained as

f ctrl = E p d31bz ò n2dxV a (t )

(11)

lp

3

3 CONTROL LAWS

The various control laws such as one control law, which is

based on Proportional Output Feedback by assuming arbitrary

value and one classical control law Proportional Integral Derivative (PID) based on state feedback and one control law

which is based on Pole Placement by state feedback has been

explained as

3.1 Control with POF controller

In the first case, the responses are taken by giving impulse

input. The Proportional Output Feedback controller is designed by taking the arbitrary value of gain. Output Feedback control provides a more consequential design. The

responses are also plotted by changing the position of sensor and actuator on the beam i.e. free end, middle end and

fixed end.

Where z is the distance between the neutral axis of the beam

and the piezoelectric layer or can be expressed as a scalar vector product as

fctrl = hV a (t ) = hu (t )

(12)

n2T is the first spatial derivative of the shape function of

where

the flexible beam, hT is a constant vector which depends on the

type of actuator and its location on the beam, given by

u(t) is nothing but

h = éêë- E p d31bz 0 E p d31bz 0ù

ú

a

û and

the control input to the actuator, i.e. V t from the controller.

If any external forces are acting on the beam, then the total

force vector becomes

()

ft = fext + fctrl .

(13)

Fig. 4 Tip displacement of cantilever beam when piezoelectric patch placed on free end

2.5 State space model of the smart cantilever beam

The following equation can be written in state space from as

follows:

*

*

M * g + C * g + K * g = f ent

+ f ctrl

= ft*

Let the states of the system be defined as

éx1 ù

g = x = ê ú=

êx2 ú

ë û

éx3 ù

ê ú and g =

êx4 ú

ë û

éx3 ù

ê ú

êx4 ú

ë û

Now equation becomes

éx3 ù

éx3 ù

éx1 ù

*

*

M * ê ú+ c * ê ú+K* ê ú= r ent

+ r ctrl

êx4 ú

êx4 ú

êx2 ú

ë û

ë û

ë û

Fig. 5 Tip displacement of cantilever beam when piezoelectric patch placed on middle end

é 0

ù

1

ú

A = ê *- 1

êë- M K * - M *- 1C *ú

û

é 0

ù

B = ê *- 1 T ú

êëM T húû

C T = éêë0 PT T ù

ú

û

D=null matrix

é 0

ù

E = ê *- 1 T úr (t )

êëM T r ú

û

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

3

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

Fig. 6 Tip displacement of cantilever beam when piezoelectric patch placed on fixed end

3.2 Control with PID controller

In a PID controller the control action s generated as a sum

of three terms. It is given by

G1 ( s ) = k p +

ki

+ kd s

s

4

end

3.3 Control with Pole placement technique

Pole Placement Technique is used to for the required control in which we can control according to the desired Eigen

vectors and frequency. The present design technique begins

with a determination of the desired closed-loop poles based on

the transient-response and/or frequency-response requirements such as Eigen vectors, damping ratio.

Kp = Proportional gain

KI = Integral gain

Kd = Derivative gain

We use

kd = 10, k p = 100, ki = 40

Fig. 7 Tip displacement of cantilever beam with and without PID controller when piezoelectric patch placed on free end

Fig. 8 Tip displacement of cantilever beam with and without PID controller when piezoelectric patch placed on middle

end

Fig. 10 Tip displacement of cantilever beam with and without Pole Placement technique when piezoelectric patch placed

on free end

Fig. 11 Tip displacement of cantilever beam with and without Pole Placement technique when piezoelectric patch placed

on middle end

Fig. 9 Tip displacement of cantilever beam with and without PID controller when piezoelectric patch placed on fixed

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

4

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

Fig. 12 Tip displacement of cantilever beam with and without Pole Placement technique when piezoelectric material on

fixed end position

[5]

[6]

4

RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS

Present work deals with the mathematical formulation and

the computational model for the active vibration control of

a beam with piezoelectric smart structure. A general

scheme of analysing and designing piezoelectric smart

structures with control laws is successfully developed in

this study. It has been observed that without control the

transient response is predominant and with control laws,

sufficient vibrations attenuation can be achieved. Numerical simulation showed that modeling a smart structure by

including the sensor / actuator mass and stiffness and by

varying its location on the beam from the free end to the

fixed end introduced a considerable change in the system’s

structural vibration characteristics. From the responses of

the various locations of sensor/actuator on beam, it has

been observed that best performance of control is obtained,

when the piezoelectric element is placed at fixed end position.

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

5

Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures 12 : 43 5-449, 2001a.

Benjeddou, A., and Deii, J.-F, “Piezoelectric transverse shear actuation and

sensing of plates, Part 2: Application and analysis’’, Journal of Intelligent Material 2001b.

Brij N Agrawal and Kirk E Treanor, “Shape control of a beam using piezoelectric actuators. Smart Material. Structure”. 8, 729–740, 1999.

Chori, S. B., Park, S. B., & Fukuda, T, “A proof of concept investigation on

Active vibration control of hybrid structures”. Mechatronics, 8, 673-689,

(1998).

Kapil Narwal and Deepak Chhabra, “Analysis of simple supported plate for

active vibration control with piezoelectric sensors and actuators”, IOSR Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering, Volume 1, Issue 1, 2278-1684, PP 2639

Kim V. V., Varadan, V. K. & Bao, X. Q., “Finite element modeling of a smart

cantilever plate and comparison with experiments”. Smart Materials and

Structures, 5, 165-170, 1996.

M. Yaqoob Yasin, Nazeer Ahmad, “Finite element analysis of actively controlled smart plate with patched actuators and sensors”. Latin American journal of solid and structure 7, 227 – 247,2010.

Manning, W. J., Plummer, A. R., & Levesley, “M. C. Vibration control of a

Flexible beam with integrated actuators and sensors”, Smart Materials and

Structures, 9, 932-939, 2000.

N.S. Viliani1, S.M.R. Khalili, “Buckling Analysis of FG Plate with Smart Sensor/Actuator’’. Journal of Solid Mechanics Vol. 1, No. 3, pp.201-212,2009.

Raja, S., Prathap G., & Sihna, P. K. “Active vibration control of composite

Sandwich beams with piezoelectric extension-bending and shear actuators”,

2002.

Singh, S. P., Pruthi, H. S., & Agarwal, V. P., “Efficient modal control strategies

for active control of vibrations”, Journal of Sound and Vibration, 262, 563575,2003.

Suleman, “Wind Tunnel Aero elastic Response of Piezoelectric and Aileron

Controlled 3-D Wing”. Can Smart Workshop Smart Materials and Structures,

Proceedings, Sep. 1998.

Sun, C.T., and Zhang, X.D., “Use of thickness-shear mode in adaptive sandwich structures”, Smart Materials and Structures 4: 202-206, 1995.

T. C. Manjunath, B. Bandyopadhyay, “Control of vibration in smart structure

using fast output sampling feedback technique’’, World Academy of Science,

Engineering and Technology 34, 2007.

Xu, S. X., & Koko, T. S, “Finite element analysis and design of actively Controlled piezoelectric smart structures”, Finite Elements in Analysis and Design, 40, 241-262, 2004.

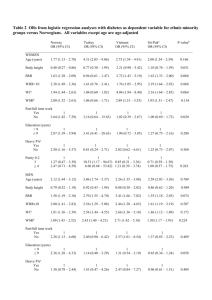

Table 1 .Active Vibration control for different types of controller

REFERENCES

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

Baillargeon, B. P., & Vel, S. S,. “Active vibration suppression of sandwich

beams using shear actuators: experiments and numerical simulations’’, Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures, 16, 517-530, 2005.

Baz and S. Poh , “Performance of an active control system with piezoelectric

actuators’’, Journal of Sound and Vibration, 126:327–343, 1988.

Benjeddou, A,, Trindade, M.A., and Ohayon, R, “New shear actuated smart

structure beam finite element’’, AIAA Journal 37(3): 378-3 83, 1999.

Benjeddou, A. and Deii, J.-F, “Piezoelectric transverse shear actuation and

sensing of plates, Part 1: A three-dimensional mixed state space formulation’’,

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

5

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

1

Performance appraisal & promotion process: A measured approach

Jitendra Kumar , Kolkata, India

Email: jkoracle23@gmail.com Phone no. :+91 9038470689

Most of the companies have yearly performance appraisal process for their employees. This process involves rating of employees by their manager.

And Companies rely purely on manager’s state of thinking and perception. Humans have tendency to become biased, corrupt, give favor to some

employees whom they like. This favor is due to some other reasons e.g. personal reason, social reason, political reason, flattering. All these reasons

are not related to the work that the employee is doing for the organization.

Employee must concentrate only on doing their work, responsibility and activities that are useful to the organization and should not bother about their

performance appraisal.

The growth of an organization is based on the work the employees do. Growth is not achieved by keeping and encouraging non performers. The organization should encourage "the doers”. This will increase the efficiency of (a) the employee (who is doing the “work”) (b) the process and (c) the

organization.

Some points worth mentioning:

(1) Some managers lack evaluation and management skills. So, in most of the cases they are unable to handle the situation properly and tend to do

mistakes. To hide their mistakes they present wrong data to the management .Because of this incorrect data, the subordinates have to do more work

than prescribed by the organization. And in most of the cases, subordinates get wrong evaluation of their performance because of this wrong data.

(2) Employees have to perform continuously. They can’t use their past performance impression to gain benefits in the present work condition.

(3) Employee work must be measured regularly. The time delay between two measurements must not be too long.

If the delay is too long then (a) We might miss some work items done by the employee

(b) Fail to give correct weightage to a piece of work.

Weekly measurement is ideal.

(4) Employee performance calculation is supposed to be on the basis of performance with respect to the goal set at the beginning of appraisal cycle.

But in most of the cases employee goals that are set (1) are not clear (2) not precisely measurable (3) work to be done in future is not known clearly

at the beginning of appraisal cycle and sometimes it changes. So manager must have access to change the goal depending on the need.

Calculation of performance on regular basis answers few questions like

(a) What is employee’s current status of performance?

(b) What is required from the employee’s?

(c) How to improve?

Important thing is, these questions are answered regularly and not at the end of performance appraisal cycle. This improves performance, efficiency,

commitment, confidence in employees.

Below are the few examples of situations generally found in many of the organizations:

(1)In an organization under manager M there are two employees E1 and E2 working on the project P1.E2 has good personal relationship with M.

Productive work done by E1 is more than E2. Now project P1 does not require two resources and there is plan to remove one resource. E2 is retained

in the project (because of good repo with M).And a plan is there to remove E1 after the performance evaluation period. So this time, M decides to

give bad rating to E1 (as E1 is not going to continue in P1 in future). In spite of doing good work E1 doesn’t get the reward that he deserves and he

gets frustrated.

Now after the end of appraisal cycle E1 is moved to some other project. Last performance evaluation data of E1 is now with E1's new manager M2.

M2 gets the impression that E1 is not so good at work after seeing the previous performance evaluation .E1 now has to prove it again his worth in

the organization.

On the other hand E2, in spite of not performing well, enjoys the good rating, good rewards and promotion.

(2)There might be a case in which an employee joins a new department.

Sometimes, the just entered employee does not get a good rating (in spite of doing good work) in the next appraisal process. This is because that employee is new to the department and has no “contacts” in the department.

(3) There are cases in which the manager M1, who is measuring the performance of an employee E1, does not work directly with E1. M1, in this

case, depends on the feedback from another employee E2, who is currently monitoring E1. And M1 rely completely on the feed back from E2. E2

feedback might not be fair or correct.

The Algorithm

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

6

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

2

This is a general idea or guide for performance appraisal process. Organizations are free to do the changes in the algorithm, depending on their need

but the core idea must not change. Below is the purpose of this algorithm

(0) Continuous evaluation: Measure the work of employees regularly so that

(a) No measurement parameter is missed (b) measurement is effective

(1) To put the performance evaluation process transparent to everyone in the organization.

(2) To increase employees confidence in the performance appraisal process.

(3) To increase the productivity of employee and of the organization.

(4) Prevents employee from wasting their time in unproductive work and doing corruption to get benefit or reward.

(5)Make the employee concentrate only on the work and not on unproductive activities.

(6) Benefits and rewards given to employee must be directly proportional to the work they do.

(7) To place an efficient, purposeful and good working culture in an organization.

(8) To increase healthy competition among employees.

(9)No Scope of favoritism.

(10) No hidden agenda, mischievous intention for an employee by other employees or by the organization.

(11)Feedback and areas of improvement is known regularly. This prevents year end surprise for an employee by the manager.

(12) Employee gets clear idea about their goal, current performance and areas of improvement regularly.

(13) Reduce conflicts.

(14) Make the performance appraisal process easier for managers.

(15) "Work" is the major parameter to measure an employee’s performance. Organization may decide some other parameters

in their policy which can be included along with “work” to measure an employee performance.

Performance Appraisal (PA) Algorithm has following steps:

Step 1: Define Performance number (PN) at organization and at project level.

Step2: Calculate the performance number regularly.

Step 3: Give rewards, increment based on performance number.

Steps details are below:

(1)Performance number (PN) definition process:

Performance number is a numeric value corresponding to a particular piece of work.

This is defined at two levels.

When defined at organizational level, this is called Organization Performance number policy (OPN).

When defined at project level, it is called project Performance number policy (PPN).

OPN Definition:

Organization must decide its organization performance number policy for each level and role.

Level here refers to designation or hierarchical level of the organization.

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

7

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

3

Organization Performance Number (OPN) This has numeric value (may be floating point value, decided by organization)

Some examples of factors that contributes to OPN

(a) On getting appreciations.

(b) Doing some work which benefited the organization

(c) Work which the organization has given some weightage that needs to be added in while calculating performance.

(d) Analysis, design, testing, implementation etc.

(f) Co-ordination, team building etc

It is better to break each OPN contributing factor into as many elements as possible and associate an OPN with each element.

More we break the work item, clearer and detailed definition of OPN will emerge.

OPN definition committee members are decided by the organization.

The OPN definition must be very comprehensive and revised frequently to improve the definition. On getting some better idea

of OPN definition, the current definition must change. This new definition might come from project performance number (PPN)

definition process or from some individuals or from some other source.

PPN Definition:

This number is similar to OPN. This is defined in detailed way at project level and the contributing factors are similar to that of OPN.

This is also not fixed and it is a continuous improving process. On getting some better idea of PPN definition, the current definition must change.

PPN definition committee contains all the project team members, managers and at least one member of OPN definition committee. The

PPN points must be in matching pattern with the OPN policy (in general).

There might be some cases where PPN definition does not match with the organization policy. But the difference must not be too high.

If the team is finding that it is not logical to be in the same pattern with the OPN policy, then they must propose this to the OPN definition

committee. The OPN definition committee has to look into this and may

change the OPN policy.

(2) Performance Number calculation process:

The manager calculates the weekly PPN and this calculation is not relative to other employees. No question of relativity arises in this process.

It is better to calculate the PPN twice in a week .First calculation at the mid of the week and last calculation at the end of the week. PPN calculation

must not go beyond two weeks .Otherwise; it will not be effective because people tend to forget the things. The weightage of performance may

not be identified after a long time effectively and correctly. If the calculation process is too late, we may forget something to add which is necessary

or may add something which is unnecessary.

At the start of yearly performance appraisal process the PPN, also known as master PPN, of each employee is set to zero. To calculate PPN, a meeting is scheduled .In PPN calculation meeting the team, the manager and the moderator are present.

The Manager evaluates the performance of each team member and prepares current measurement cycle PPN. This current PPN is added to the master

PPN in presence of the team.

During calculation process the whole team should be present so that they can see if the calculation of every one is happening properly .At PPN calculation time the master PPN and the current PPN ,just calculated, is visible to the whole team.

Any issue arising out of the meeting must be routed to the moderator for resolution. And after getting resolution the current PPN is revised.

Role of moderator: Moderator is the hawk eye on the calculation process.

Moderator has to ensure

(1) Calculation is taking place fairly and with no discrepancy.

(2) Calculation is taking place according to OPN and PPN policy.

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

8

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

4

(3) The grievance are addressed properly .If needed the moderator can seek the help of other moderators or OPN definition committee members.

(4) If new PPN definition is proposed then it must be passed to OPN definition committee to evaluate.

Moderator is invisible to the whole team and the manager.

Only written and verbal communication is done. The setup is such that the team and the manager never get the idea about the identity of the moderator and vice versa. Make both sides invisible to each other. This will help in transparency and no favoritism by the moderator.

This invisibility and masking is important.

Example: case 1: Moderator M identity is known to team member M1.

M1 may influence M to give him favor in any dispute.

Case 2: Moderator M identity is known to manager MGR.

MGR may influence M to give him the favor in any dispute.

Case 3: Moderator M1 is manager of project P1. Moderator M2 is manager of project P2.

M1 and M2 know each other. There might be the case that M1 is moderating P2 and M2 is moderating P1. Both M1 and M2

might bend the rule in their favor and do incorrect calculation.

Below is an example of PPN versus employee graph.

Above flow chart indicates employees project performance number in a project.

X axis represnts performance number and Y axis represents individual employee shown as e1,e2,e3..

(3) Rewards and recognition process:

Rewards and recognition is directly proportional to the PPN earned by an employee. The Organization decides whether the reward is distributed

based on Level or role of an employee.

For each employee, there will be a level performance number (LPN) for a level .Change in LPN will be done at the end of yearly appraisal cycle and

the change is directly proportional to the PPN earned . When ever there is plan to move some employees from one level to other level (it is called

promotion in most of the cases) then this LPN is the only reference document.

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

9

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

5

This movement may be from higher level to lower level or lower level to higher level. Top LPN holders are moved first (in the movement from lower

level to higher level).

When ever one employee is moved from one level to other then the employees LPN is set to zero. And each year the LPN is revised (some points

added or deducted).LPN will remain present till the employee stays in that level. So the life of the LPN is for a particular level only. New level corresponds to new LPN.

There is a Set rating number (SRN) .SRN is any floating or whole number decided by the organization. SRN is a variable. It might be same for a

level or same for a project or same for a role, or some other factors. But it must be common for a group.

Reward or increment at the end of appraisal cycle is calculated as below:

Total reward (TR) = PPN*SRN *base pay

Base pay is decided by the organization. It might be (a) level base pay which is fixed for a level and this is implemented at every position or (b) the

last years pay.

This total reward might be increment or one time payment or any other thing.

Yearly performance appraisal cycle flow:

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

10

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

6

Promotion flow:

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I wish to thank Arvind Pal Singh, Vishal Narula and Varun Lakhotia for their review and important suggestion to improve this

work.

REFRENCES: NO REFRENCES

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

11

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

1

On New Separation Axioms Via γ-Open Sets*

Hariwan Z. Ibrahim

Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, University of Zakho, Kurdistan-Region, Iraq.

Email: hariwan_math@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

In this paper, we introduce two new classes of topological spaces called γ-R0 and γ-R1 spaces in terms of the concept of γ-open

sets and investigate some of their fundamental properties.

Keywords : γ-open, γ-closure, γ-R0 spaces and γ-R1 spaces.

1 INTRODUCTION

T

HE notion of R0 topological spaces is introduced by Shanin

[4] in 1943. Later, Davis [2] rediscovered it and studied

some properties of this weak separation axiom. In the

same paper, Davis also introduced the notion of R1 topological

space which are independent of both T0 and T1 but strictly

weaker than T2. The notion of γ-open sets was introduced by

Ogata [3]. In this paper, we continue the study of the above

mentioned classes of topological spaces satisfying these

axioms by introducing two more notions in terms of γ-open

sets called γ-R0 and γ-R1.

2 Preliminaries

Throughout the present paper, (X, τ) and (Y, σ) (or simply X

and Y) denotes a topological spaces on which no separation

axioms is assumed unless explicitly stated. Let A be a subset of

a topological space X. The closure of A is denoted by Cl(A).

Definition 2.1. [3] Let (X, τ) be a topological space. An operation

γ on the topology τ is a mapping from τ in to power set P(X) of X

such that V ⊆ γ(V) for each V ∈ τ, where γ (V) denotes the value of

γ at V.

Definition 2.2. [3] A subset A of a topological spac (X, τ) is

called γ-open set if for each x ∈ A there exists an open set U

such that x ∈ U and γ(U) ⊆ A. Complements of γ-open sets are

called γ-closed.

γO(X) denotes the collection of all γ-open sets of (X, τ).

Moreover, γC(X) denotes the collection of all γ-closed sets of

(X, τ).

Definition 2.3. *1+ A γ-nbd of x ∈ X is a set U of X which contains a γ-open set V containing x.

Definition 2.4. *3+ The intersection of all γ-closed sets containing A is called the γ-closure of A and is denoted by τγ-Cl(A).

3 γ-R0 and γ-R1 spaces

We introduce the following definitions.

Definition 3.1. Let A be a subset of a topological space (X, τ)

and γ be an operation on τ. The γ-kernel of A, denoted by

γker(A) is defined to be the set

γker(A) = ∩ {U ∈ γO(X): A ⊆ U}.

Lemma 3.2. Let (X, τ) be a topological space with an operation

γ on τ and x ∈ X. Then y ∈ γker(,x}) if and only if x ∈ τγCl({y}).

Proof. Suppose that yγker(,x}). Then there exists a γ-open set

V containing x such that y V. Therefore, we have x τγCl({y}). The proof of the converse case can be done similarly.

Theorem 3.3. Let (X, τ) be a topological space with an operation γ on τ and A be a subset of X. Then, γker(A) = ,x ∈ X: τγCl(,x}) ∩ A≠ φ}.

Proof. Let x ∈ γker(A) and suppose τγ-Cl({x}) ∩ A = φ. Hence x

X \τγ-Cl(,x}) which is a γ-open set containing A. This is impossible, since x ∈ γker(A). Consequently, τγ-Cl(,x}) ∩ A≠ φ.

Next, let x ∈ X such that τγ-Cl(,x}) ∩ A≠ φ and suppose that x

γker(A). Then, there exists a γ-open set V containing A and x

V. Let y ∈ τγ-Cl(,x}) ∩ A. Hence, V is a γ-nbd of y which does

not contain x. By this contradiction x ∈ γker(A) and the claim.

Theorem 3.4. The following properties hold for the subsets A,

B of a topological space (X, τ) with an operation γ on τ:

1.

A ⊆ γker(A).

2.

A ⊆ B implies that γker(A) ⊆ γker(B).

3.

If A is γ-open in (X, τ), then A = γker(A).

4.

γker(γker(A)) = γker(A).

Proof. (1), (2) and (3) are immediate consequences of

Definition 3.1. To prove (4), first observe that by (1) and (2), we

have γker(A) ⊆ γker(γker(A)). If x γker(A), then there exists

U ∈ γO(X) such that A ⊆ U and x U. Hence γker(A) ⊆ U,

and so we have x γker(γker(A)). Thus γker(γker(A)) =

γker(A).

Definition 3.5. A topological space (X, τ) with an operation

operation γ on τ, is said to be γ-R0 if U is a γ-open set and x ∈

U then τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆ U.

Theorem 3.6. For a topological space (X, τ) with an operation γ

operation γ on τ, the following properties are equivalent:

1. (X, τ) is γ-R0.

2. For any F ∈ γC(X), x F implies F ⊆ U and x U for

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

12

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

3.

4.

some U ∈ γO(X).

For any F ∈ γC(X), x F implies F ∩ τγ-Cl(,x}) = φ.

For any distinct points x and y of X, either τγ-Cl({x}) =

τγ-Cl(,y}) or τγ-Cl(,x}) ∩ τγ-Cl(,y}) = φ.

Proof. (1) ⇒ (2). Let F ∈ γC(X) and x F. Then by (1), τγ-Cl({x})

⊆ X \ F . Set U = X \τγ-Cl({x}), then

U is a γ-open set

such that F ⊆ U and x U.

(2) ⇒ (3). Let F ∈ γC(X) and x F. There exists U ∈ γO(X) such

that F ⊆ U and x U. Since U ∈ γO(X), U ∩ τγ-Cl(,x}) = φ and

F ∩ τγ-Cl(,x}) = φ.

(3) ⇒ (4). Suppose that τγ-Cl({x}) ≠ τγ-Cl({y}) for distinct

points x, y ∈ X. There exists z ∈ τγ-Cl({x}) such that z τγCl({y}) (or z ∈ τγ-Cl({y}) such that z τγ-Cl({x})). There exists V

∈ γO(X) such that y V and z ∈ V; hence x ∈ V. Therefore, we

have x τγ-Cl({y}). By (3), we obtain τγ-Cl(,x}) ∩ τγ-Cl(,y}) = φ.

(4) ⇒ (1). let V ∈ γO(X) and x ∈ V. For each y V, x ≠ yand x

τγ-Cl(,y}). This shows that τγ-Cl({x}) ≠ τγ-Cl(,y}). By (4), τγCl(,y}) = φ for each y ∈ X\V and hence τγ-Cl(,x}) ∩ (∪y∈X\V τγCl(,y})) = φ. On other hand, since V ∈ γO(X) and y ∈ X\V, we

have τγ-Cl({y}) ⊆ X \ V and hence X \ V = ∪ y∈X \V τγ-Cl({y}).

Therefore, we obtain (X \ V ) ∩ τγ-Cl(,x}) = φ and τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆

V. This shows that (X, τ) is a γ-R0 space.

Theorem 3.7. For a topological space (X, τ) with an operation γ

on τ, the following properties are equivalent:

1. (X, τ) is γ-R0.

2. x ∈ τγ-Cl({y}) if and only if y ∈ τγ-Cl({x}), for any

points x and y in X.

Proof. (1) ⇒ (2). Assume that X is γ-R0. Let x ∈ τγ-Cl({y}) and V

be any γ-open set such that y ∈ V. Now by hypothesis, x ∈ V.

Therefore, every γ-open set which contain y contains x. Hence

y ∈ τγ-Cl({x}).

(2) ⇒ (1). Let U be a γ-open set and x ∈ U. If y U, then x τγCl({y}) and hence y τγ-Cl(,x}). This implies that τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆

U. Hence (X, τ) is γ-R0.

Theorem 3.8. The following statements are equivalent for any

points x and y in a topological space (X, τ) with an operation γ

on τ:

1. γker(,x}) ≠ γker(,y}).

2. τγ-Cl({x}) ≠ τγ-Cl({y}).

Proof. (1) ⇒ (2). Suppose that γker(,x}) ≠ γker(,y}), then there

exists a point z in X such that z ∈ γker(,x}) and z γker(,y}).

From z ∈ γker(,x}) it follows that ,x} ∩ τγ-Cl({z}) ≠ φ which implies x ∈ τγ-Cl({z}). By z γker(,y}), we have ,y} ∩ τγ-Cl({z}) =

φ. Since x ∈ τγ-Cl({z}), τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆ τγ-Cl({z}) and ,y} ∩ τγ-Cl({x})

= φ. Therefore, it follows that τγ-Cl({x}) ≠ τγ-Cl({y}). Now

γker(,x}) ≠ γker(,y}) implies that τγ-Cl({x}) ≠ τγ-Cl({y}).

(2) ⇒ (1). Suppose that τγ-Cl({x}) ≠ τγ-Cl({y}). Then there exists

a point z in X such that z ∈ τγ-Cl({x}) and z τγ-Cl({y}). Then,

there exists a γ-open set containing z and therefore x but not y,

namely, y γker(,x}) and thus γker(,x}) ≠ γker(,y}).

Theorem 3.9. Let(X, τ) be a topological space and γ be an operation on τ. Then ∩ ,τγ-Cl({x}) : x ∈ X} = φ if and only if

2

γker(,x}) ≠ X for every x ∈ X.

Proof. Necessity. Suppose that ∩,τγ-Cl({x}) : x ∈ X} = φ. Assume that there is a point y in X such that γker(,y}) = X. Let x

be any point of X. Then x ∈ V for every γ-open set V containing y and hence y ∈ τγ-Cl({x}) for any x ∈ X. This implies that y

∈ ∩ ,τγ-Cl({x}) : x ∈ X}. But this is a contradiction.

Sufficiency. Assume that γker(,x}) ≠ X for every x ∈ X. If there

exists a point y in X such that y ∈ ∩ ,τγ-Cl({x}) : x ∈ X}, then

every γ-open set containing y must contain every point of X.

This implies that the space X is the unique γ-open set containing y. Hence γker(,y}) = X which is a contradiction. Therefore,

∩ ,τγ-Cl({x}) : x ∈ X} = φ.

Theorem 3.10. A topological space (X, τ) with an operation γ

on τ is γ-R0 if and only if for every x and y in X,

τγ-Cl({x}) ≠ τγ-Cl(,y}) implies τγ-Cl(,x}) ∩ τγ-Cl(,y}) = φ.

Proof. Necessity. Suppose that (X, τ) is γ-R0 and τγ-Cl({x})≠ τγCl({y}). Then, there exists z ∈ τγ-Cl({x}) such that z τγ-Cl({y})

(or z ∈ τγ-Cl({y}) such that z τγ-Cl({x})). There exists V ∈

γO(X) such that y V and z ∈ V, hence x ∈ V. Therefore, we

have x τγ-Cl({y}). Thus x ∈ [X \τγ-Cl({y})] ∈ γO(X), which

implies τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆ [X \ τγ-Cl(,y})+ and τγ-Cl(,x}) ∩ τγ-Cl({y}) =

φ.

Sufficiency. Let V ∈ γO(X) and let x ∈ V. We still show that τγCl({x}) ⊆ V. Let y V, that is y ∈ X\V. Then x ≠ y and x τγCl(,y}). This shows that τγ-Cl({x}) ≠ τγ-Cl({y}). By assumption,

τγ-Cl(,x}) ∩ τγ-Cl(,y}) = φ. Hence y τγ-Cl(,x}) and therefore τγCl({x}) ⊆ V .

Theorem 3.11. A topological space (X, τ) with an operation γ

on τ is γ -R0 if and only if for any points x and y in X, γker(,x})

≠ γker(,y}) implies γker(,x}) ∩ γker(,y}) = φ.

Proof. Suppose that (X, τ) is a γ-R0 space. Thus by Theorem

3.8, for any points x and y in X if γker(,x}) ≠ γker(,y}) then τγCl({x}) ≠ τγ-Cl(,y}). Now we prove that γker(,x}) ∩ γker(,y}) =

φ. Assume that z ∈ γker(,x}) ∩ γker(,y}). By z ∈ γker(,x}) and

Lemma 3.2, it follows that x ∈ τγ-Cl({z}). Since x ∈ τγ-Cl({x}), by

Theorem 3.6, τγ-Cl(,x}) = τγ-Cl({z}). Similarly, we have τγCl(,y}) = τγ-Cl(,z}) = τγ-Cl({x}). This is a contradiction. Therefore, we have γker(,x}) ∩ γker(,y}) = φ.

Conversely, let (X, τ) be a topological space such that for any

points x and y in X, γker(,x}) ≠ γker(,y}) implies γker(,x}) ∩

γker(,y}) = φ. If τγ-Cl({x}) ≠ τγ-Cl({y}), then by Theorem 3.8,

γker(,x}) ≠ γker(,y}). Hence, γker(,x}) ∩ γker(,y}) = φ which

implies τγ-Cl(,x}) ∩ τγ-Cl(,y}) = φ. Because z ∈ τγ-Cl({x}) implies

that x ∈ γker(,z}) and therefore γker(,x}) ∩ γker(,z}) ≠ φ. By

hypothesis, we have γker(,x}) = γker(,z}). Then z ∈ τγ-Cl(,x}) ∩

τγ-Cl(,y}) implies that γker(,x}) = γker(,z}) = γker(,y}). This is a

contradiction. Therefore, τγ-Cl(,x}) ∩ τγ-Cl({y}) = φ and by

Theorem 3.6, (X, τ) is a γ-R0 space.

Theorem 3.12. For a topological space (X, τ) with an operation

operation γ on τ, the following properties are equivalent:

1. (X, τ) is a γ-R0 space.

2. For any non-empty set there exists F ∈ γC(X) such

that A ∩ F ≠ φ and F ⊆ G.

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

13

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

3. For any G ∈ γO(X), we have G = ∪ {F ∈ γC (X): ⊆ G}.

4. For any F ∈ γC(X), we have F = ∩ {G ∈ γO(X): F ⊆ G}.

5. For every x ∈ X, τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆ γker(,x}).

Proof. (1) ⇒ (2). Let A be a non-empty subset of X and G ∈

γO(X) such that A ∩ G ≠ φ. There exists x ∈ A ∩ G. Since x ∈ G

∈ γO(X), τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆ G. Set F = τγ-Cl({x}), then F ∈ γC(X), F ⊆

G and A ∩ F ≠ φ.

(2) ⇒ (3). Let G ∈ γO(X), then G ⊇ ∪ {F ∈ γC(X): F ⊆ G}. Let x

be any point of G. There exists F ∈ γC(X) such that x ∈ F and F

⊆ G. Therefore, we have x ∈ F ⊆ ∪ {F ∈ γC (X): F⊆ G} and

hence G = ∪ {F ∈ γC(X): F ⊆ G}.

(3) ⇒ (4). Obvious.

(4) ⇒ (5). Let x be any point of X and y γker(,x}). There exists V ∈ γO(X) such that x ∈ V and y V, hence τγ-Cl(,y}) ∩ V

= φ. By (4), (∩ {G ∈ γO(X): τγ-Cl({y}) ⊆ G}) ∩ V = φ and there

exists G ∈ γO(X) such that x G and τγ-Cl({y}) ⊆ G. Therefore

τγ-Cl(,x}) ∩ G = φ and y τγ-Cl({x}). Consequently, we obtain

τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆ γker(,x}).

(5) ⇒ (1). Let G ∈ γO(X) and x ∈G. Let y ∈ γker(,x}), then x ∈

τγ-Cl({y}) and y ∈ G. This implies that γker(,x}) ⊆ G. Therefore,

we obtain x ∈ τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆ γker(,x}) ⊆ G. This shows that (X, τ)

is a γ-R0 space.

Corollary 3.13. For a topological space (X, τ) with an operation

γ on τ, the following properties are equivalent:

1. (X, τ) is a γ-R0 space.

2. τγ-Cl(,x}) = γker(,x}) for all x ∈ X.

Proof. (1) ⇒ (2). Suppose that (X, τ) is a γ-R0 space. By Theorem 3.12, τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆ γker(,x}) for each x ∈ X. Let y ∈ γker(,x}),

then x ∈ τγ-Cl(,y}) and by Theorem 3.6, τγ-Cl(,x}) = τγ-Cl({y}).

Therefore, y ∈ τγ-Cl(,x}) and hence γker(,x}) ⊆ τγ-Cl({x}). This

shows that τγ-Cl(,x}) = γker(,x}).

(2) ⇒ (1). Follows from Theorem 3.12.

Theorem 3.14. For a topological space (X, τ) with an operation

γ on τ, the following properties are equivalent:

1.

(X, τ) is a γ-R0 space.

2.

If F is γ-closed, then F = γker(F).

3.

If F is γ-closed and x ∈ F, then γker(,x}) ⊆ F.

4.

If x ∈ X, then γker(,x}) ⊆ τγ-Cl({x}).

Proof. (1) ⇒ (2). Let F be a γ-closed and x F. Thus (X\F) is a

γ-open set containing x. Since (X, τ) is γ-R0, τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆ (X\F).

Thus τγ-Cl({x}) ∩ F = φ and by Theorem 3.3, x γker(F). Therefore γker(F) = F.

(2) ⇒ (3). In general, A ⊆ B implies γker(A) ⊆ γker(B). Therefore, it follows from (2), that γker(,x}) ⊆ γker(F ) = F.

(3) ⇒ (4). Since x ∈ τγ-Cl(,x}) and τγ-Cl(,x}) is γ-closed, by (3),

γker(,x}) ⊆ τγ-Cl({x}).

(4) ⇒ (1). We show the implication by using Theorem 3.7. Let x

∈ τγ-Cl({y}). Then by Lemma 3.2, y ∈ γker(,x}). Since x ∈ τγCl(,x}) and τγ-Cl(,x}) is γ-closed, by (4), we obtain y ∈ γker(,x})

⊆ τγ-Cl({x}). Therefore x ∈ τγ-Cl({y}) implies y ∈ τγ-Cl({x}). The

converse is obvious and (X, τ) is γ-R0.

Definition 3.15. A topological space (X, τ) with an operation γ

on τ, is said to be γ-R1 if for x, y in X with τγ-Cl({x}) ≠ τγCopyright © 2012 SciResPub.

3

Cl(,y}), there exist disjoint γ-open sets U and V such that τγCl({x}) ⊆ U and τγ-Cl({y}) ⊆ V.

Theorem 3.16. For a topological space (X, τ) with an operation

γ on τ, the following statements are equivalent:

1. (X, τ) is γ-R1.

2. If x, y ∈ X such that τγ-Cl({x}) ≠ τγ-Cl({y}), then there

exist γ-closed sets F1and F2such that x ∈ F1, y F1, y ∈

F2, x F2 and X = F1 ∪ F2.

Proof. Obvious.

Theorem 3.17. If (X, τ) is γ-R1, then (X, τ) is γ-R0.

Proof. Let U be γ-open such that x ∈ U. If y U, since x τγCl(,y}), we have τγ-Cl({x}) ≠ τγ-Cl(,y}). So, there exists a γ-open

set V such that τγ-Cl({y}) ⊆ V and x V, which implies y τγCl({x}). Hence τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆ U . Therefore, (X, τ) is γ-R0.

The converse of the above Theorem need not be ture in general

as shown in the following example.

Example 3.18. Consider X = {a, b, c} with the discrete topology

on X. Define an operation γ on τ by γ(A) = A if A = {a, b} or {a,

c} or {b, c} and γ(A) = X otherwise. Then X is a γ-R0 space but

not a γ-R1 space.

Corollary 3.19. A topological space (X, τ) with an operation γ

on τ is γ-R1 if and only if for x, y ∈ X, γker(,x}) ≠ γker(,y}),

there exist disjoint γ-open sets U and V such that τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆

U and τγ-Cl({y}) ⊆ V.

Proof. Follows from Theorem 3.8.

Theorem 3.20. A topological space (X, τ) is γ-R1 if and only if x

∈ X\τγ-Cl(,y}) implies that x and y have disjoint γ-nbds.

Proof. Necessity. Let x ∈ X\τγ-Cl({y}). Then τγ-Cl({x}) ≠ τγCl(,y}), so, x and y have disjoint γ-nbds.

Sufficiency. First, we show that (X, τ) is γ-R0. Let U be a γopen set and x ∈ U. Suppose that y U. Then, τγ-Cl(,y}) ∩ U =

φ and x τγ-Cl({y}). There exist γ-open sets Ux and Uy such

that x ∈ Ux, y ∈ Uy and Ux ∩ Uy = φ. Hence, τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆ τγCl(Ux) and τγ-Cl(,x}) ∩ Uy ⊆ τγ-Cl(Ux) ∩ Uy = φ. Therefore, y

τγ-Cl({x}). Consequently, τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆ U and (X, τ) is γ-R0. Next,

we show that (X, τ) is γ-R1. Suppose that τγ-Cl({x}) ≠ τγ-Cl({y}).

Then, we can assume that there exists z ∈ τγ-Cl({x}) such that z

τγ-Cl(,y}). There exist γ-open sets Vz and Vy such that z ∈ Vz,

y ∈ Vy

And Vz ∩ Vy = φ. Since z ∈ τγ-Cl({x}), x ∈ Vz. Since (X, τ) is γ-R0,

we obtain τγ-Cl({x}) ⊆ Vz, τγ-Cl({y}) ⊆ Vy and Vz ∩ Vy = φ. This

shows that (X, τ) is γ-R1.

REFERENCES

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

Ahmad, B. and Hussain, S., Properties of γ-operations in Topological

Spaces, The Aligarh Bulletin of Mathematics, 22 (1) (2003), 45-51.

Davis, A. S., Indexed systems of neighborhoods for general topological spaces, Amer. Math. Monthly, 68 (1961), 886-893.

Ogata, H., Operation on topological spaces and associated topology,

Math. Japonica, 36 (1) (1991), 175-184.

Shanin, N. A., On separation in topological spaces, Dokl. Akad.

Nauk. SSSR, 38 (1943), 110-113.

14

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

1

Temperature Based Condition Monitoring of Rail and

Structural Mill

Lakhan Patidar, Chitragupt Swaroop Chitransh, K.U. Rao

1

Asst. Prof., Department of Mechanical Engineering, SIRT-Excellence, Bhopal, Email Id:- lakhanmanit@rediffmailmail.com, Chitragupt

Swaroop Chitransh

2

M-Tech Student, Department of Mechanical Engineering, MANIT, Bhopal, Email Id:- chitransh86@yahoo.com, K.U. Rao

3

DGM in CBMS Department SAIL BSP, Bhilai (C.G.), Email Id:- kurao@sail-bhilaisteel.com

Abstract— today in this competitive market it is necessary to reduce

shutdowns and to increase our production rate. For this purpose we

apply Condition Monitoring Methods. SAIL is the world‟s largest

producer of rails with an installed capacity to produce 500 000 tons of

rails and 250 000 tons of structural‟s. Bhilai is also the sole supplier

of the country's longest rail tracks of 260 meters. Infrared

Thermography is the latest Condition Monitoring technique that is

adopted in Bhilai Steel Plant. Predictive Maintenance schemes are

being practiced in Bhilai Steel Plant to monitor the health of the

equipment and identify potential problems well in advance and plan

remedial measures, thereby avoiding unwanted failures.

Keywords: Predictive Maintenance, Thermo vision camera, Thermo

graphic image viewer software, Rail and Structural Mill, Temperature

Based Condition Monitoring, Thermo graphic images

—————————— ——————————

I. INTRODUCTION

Rail and Structural Mill in Bhilai Steel Plant produces mainly

rails and heavy structural‟s and is equipped with many complex

electrical drives. So, it is necessary to do proper health

monitoring of equipments. For this purpose we apply predictive

maintenance tool. In addition regular maintenance practices,

Thermography, a condition monitoring technique is also

applied to evaluate the condition of related electrical

equipments and cables, reactor, DC Circuit breaker, cable

joints etc., to prevent any unforeseen breakdowns. The main

reason behind to do Thermography, it is a non invasive non

contact method for even far away locations with higher

accuracy.

II. METHOD

Firstly we take thermal images of a particular region or surface,

and then we apply analytical approach with the help of Thermo

graphic image viewer software, if there found any higher

temperature on any point then we mark them as hot spots. With

the help of hot spots we are able to find out higher side

temperature range on a particular point. It is a modern approach

to find out hot spots in our shorter time. Through this technique

we can generate hot spots on different points on a single

surface. Accuracy level may be vary depends on software user.

The Major Profiles Produced in the RSM Mill are

1. Rails

a) IRS 52 Kg/m

b) Thick Web Asymmetric Rail

2. Heavy Beams

a) 600 * 210 * 12 mm

b) 500 * 180 * 10.2 mm

c) 450 * 150 * 9.4 mm

d) 400 * 140 * 8.9 mm

e) 350 * 140 * 7.5 mm

f) 50 * 125 * 6.9 mm

3. Channels

a) 400 * 100 * 8.8 mm

b) 300 * 90 * 7.6 mm

c) 250 * 82 * 7.6 mm

4. Angles

a) 200 * 200 * 20/16 mm

b) 150 * 150 * 20/16 mm

5.) Crane Rails

a) CR 120

b) CR 100

c) CR 80

6.) Crossing Sleepers

a) It depends as per requirement 80kg/mm², 100 kg/mm²,

120 kg/mm².

Introduction of Power Supply Units

For 1 D motor:

Power capacity: 4 MW ,

Speed : 70 rpm

Current carrying capacity : 4940 amp

Supply : 865 V

For 2D motor:

Power capacity: 7.1 MW

Speed : 90 rpm

Current carrying capacity : 6190 amp

Supply : 8040 V

Transformer: 11KV and 6.6 kV, capacity to step down

11000V, 6600V into 850V supply.

Different components used in power transmission unit for RSM

a) Copper cables 150 square mm.

b) Normal nut bolt joints.

c) Circuit Breaker, Load bearing capacity up to 8KA.

d) Reactors, to filter current into pure D.C.

Supply.

e) Thyristors, to convert AC supply into DC supply.

f) D.C. motor, to supply rectified power in different

Sections.

III. PURPOSE TO DO THERMOGRAPHY

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

15

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

2

In Bhilai Steel Plant, Rail and Structural Mill Shop Machine

works on very high temperature to produce temperature up to

1300°c. So proper temperature monitoring is essential to reduce

hazards. To reduce hazards of failure we apply Thermography.

Thermo graphic Images of Different Power Units at Rail &

Structural Mill (RSM) Shop, Sail BSP.

(Before Repair)

(After Repair)

Fig.4 Description: RSM 2D DCCB1 Reactor bottom

(Before Repair)

(After Repair)

Fig.1 Description RSM Busbar of 1DDCCB2 (At shunt)

(Before Repair)

(After Repair)

Fig.5 Description: RSM 2D DCCB2 Reactor

(Before Repair)

(After Repair)

Fig.2 Description RSM Busbar of 1DDCCB1 (At Shunt)

(Before Repair)

(After Repair)

Fig.3 Description: RSM Bus bar of 1D DCCB

(Before Repair)

(After Repair)

Fig.6 Description: RSM 1D/2 Reactors

(Before Repair)

(After Repair)

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

16

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

Fig.7 Description: RSM 2D DCCB outgoing

3

Temp◦c ↑

Readings on 15/03/2010→

Discussions

IV. RESULT AND DISCUSSIONS

Graph1.)

Above graph shows that readings taken on 15/03/2010 having

higher side temperature readings, when we compared it with

previous readings at 1,2,3,4,5 it shows temperature more than

caution range then we mark it as in alarm range generally

represented by red color. But at 6, 7 temperatures is in caution

range generally represented by yellow color. To reduce

temperature at different units firstly check for looseness of

joints and cables, if fault not found then we cut a loop of cable

for testing purpose. It is generally cut where temperature range

is in alarm range. After testing if there problem exist

insulation then we change cable for that particular area. But in

this case, temperature increasing due to looseness of joints.

After tightening of joints temperature come into its normal

range.

Temp◦c ↑

Readings on 15/02/2010→

Where, 1 = Temperature at bus bar of 1D DCCB2.

2 = Temperature at bus bar of 1D DCCB2.

3 = Temperature at outgoing bus bar of

1DDCCB Bottom.

4 = Temperature at 2D DCCB1 reactor.

5 = Temperature at 2D DCCB2 reactor.

6 = Temperature at 1D/2 reactor.

7 = Temperature at 2D DCCB outgoing.

Discussions

Above graph shows reading taken on 15/02/2010 at different

power supply units of Rail & Structural Mill Shop, BSP. With

the help of graph we can easily find out temperature range for

different power units represented by 1,2,3,4,5,6,7. In this graph

1, 3, 4,5,6,7 having temperature of normal range but at 2

temperatures are more than normal range which marked as in

caution range. Generally represented by yellow color.

Graph2.)

Graph3.)

Temp◦c↑

Readings on 20/03/2010→

Discussions:

Above graph shows that readings taken on 20/03/2010 still

having higher side temperature at 4, 5, then we marked it as in

caution range. Other readings are in normal range. To reduce

this excessive temperature, we check looseness of cables and

joints if there found any looseness then resolve it by taking

proper action. The reason for increasing temperature at 4, 5 is

looseness of clamping nut bolts. After repair temperature is

minimized.

Graph4.)

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

17

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

4

benefits which show that Thermography is a very effective

predictive tool to reduce catastrophic hazards in our short time.

The above mentioned applications clearly indicate the

usefulness of Infrared Thermography as an effective condition

monitoring tool. Locating the surface „Hot spots‟ developed

due to internal defects in critical units and loose connections in

electrical joints well in advance and taking corrective

measures well in time

has helped in avoiding many

breakdown in Bhilai Steel Plant. Thus Infrared Thermography

utilizing Thermo vision camera has become a very powerful

resource for Predictive Maintenance in Bhilai Steel Plant.

Temp◦c↑

Readings on 25/03/2010→

Discussions

Above graph shows that all readings are in normal range taken

on 25/03/2010.It shows that no maintenance work is needed at

this stage. With the help of „hot spots‟ we can easily find out

excessive temperature at a particular point.

Remedies

Installation of highly resistive copper nut bolts.

Installation of clamping must be done by experts only.

Regular monitoring of loose parts at different power

supply units.

Installation of good insulated power cables.

Installation of highly efficient circuit breaker.

Proper installation of bus bars and cable joints.

Result

Total energy savings at different units:

Energy savings at 1

↔ 44.45%

Max energy savings at 2 ↔ 60.34%

Energy savings at 3

↔ 39.08%

Energy savings at 4

↔ 39.58%

Energy savings at 5

↔ 34.45%

Energy savings at 6

↔ 45.21%

Energy savings at 7

↔ 28.57%

Overall savings → (1+2+3+4+5+6+7) / 7 → 41.67%

Advantages of Thermography

Quick problem detection without interrupting service.

Prevention of premature failure and extension of

equipment life.

Identification of potentially dangerous or hazardous

equipment.

Can monitor target in motion and also low visibility

target.

Temperature profile can be recorded and displayed

easily.

Can monitor targets electricity charged. (high voltage

equipments)

Can also monitor small and remote items.

Disadvantages of Thermography

Formula Used

Energy savings ↔ 100-{(Min Temp/ Max. Temp.) * 100}

Overall savings ↔ ∑ savings at different units /7

Cost of instrument is relatively high.

Unable to detect the inside temperature if the medium

is separated by glass/polythene material etc.

PIE CHART FOR ENERGY SAVINGS PERCENTAGE AT DIFFERENT UNITS

.

28.57

REFERENCES

44.45

[1]

1

45.21

2

[2]

3

60.34

34.45

4

5

[3]

6

7

[4]

39.58

39.08

[5]

[6]

IV. CONCLUSION

Through proper condition monitoring with the help of

Thermography the improvement achieved in different units of

rail & structural mill shop at BSP can be easily observed from

above Thermo graphic images. The excessive temperature is

minimized up to its normal range within 1 month. These are the

[7]

[8]

[9]

Mr.K.U.Rao, a paper presentation on “Thermography” in Bhilai steel

Plant, July 2007.

R. E. Martin, A. L. Gyekenyesi, S. M. Shepard, “Interpreting the Results

of Pulsed Thermography Data,” Materials Evaluation, Vol. 61, no. 5, pp.

611-616, 2003.

N. Rajic, “Principal component Thermography for flaw contrast

enhancement and flaw depth Characterization in composite structures,”

Composite Structures Vol. 58, pp. 521-528, 2002.

X. P. V. Maldague, Theory and Practice of Infrared Technology for

Nondestructive Testing, John Wiley-Inter science, 684 p., 2001.

Mr. S.P.Garnik, a paper presentation on “Thermography - A Condition

monitoring tool for process1063-1069, 2006.

M. Pilla, M. Klein, X. Maldague and A.Salerno, “New Absolute

Contrast for Pulsed Infrared Physics & Technology”, 53(2), 112-119,

2010.

Mr. S.P.Garnik, a paper presentation on “Thermography - A Condition

monitoring tool for process Industries, FICCI (Federation of Indian

chambers of commerce & industry), 15th Feb 2007.

Higgins Lindley R. et.all,‛Maintenance Engineering Hand Book”,

McGraw-Hill Inc New York.

Andreas Gleiter, Guenther Mayr “Infrared Physics & Technology”,

53(4), 288-291, 2010.

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

18

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

[10]

M. Ochs, A. Schulz, H.-J. Bauer “Infrared Physics & Technology”,

5

53(2), 112-119, 2010.

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

19

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

1

Design and realization of a quantum Controlled NOT

gate using optical implementation

K. K. Biswas, Shihan Sajeed

1(

Department of Applied Physics, Electronics and Communication Engineering (APECE), University of Dhaka, Bangladesh.(Phone: =

+8801724119834; e-mail: shorbiswas.377@gmail.com).

2

(Department of Applied Physics, Electronics and Communication Engineering (APECE), University of Dhaka, Bangladesh. (Phone: =

+8801817094868; e-mail: Shihan.sajeed@gmail.com)

ABSTRACT

In this work an optical implementation technique of a Controlled-NOT (CNOT) gate has been designed, realized and

simulated. The polarization state of a photon is used as qubit. The interaction required between two qubits for realizing the

CNOT operation was achieved by converting the qubits from polarization encoding to spatial encoding with the help of a

0

Polarizing Beam Splitter (PBS) and half wave plate (HWP) oriented at 45 . After the nonlinear interference was achieved the

spatially encoded qubits were converted back into polarization encoding and thus the CNOT operation was realized. The

whole design methodology was simulated using the simulation software OptiSystem and the results were verified using the

built-in instruments polarization analyzer, polarization meter, optical spectrum analyzer, power meters etc.

Keywords - Qubit, Quantum gate, Polarizing Beam Splitter, Half Wave Plate, Beam Splitter, Dual rail technique.

1 INTRODUCTION

2 Theory

Q

2.1 Representation of Quantum CNOT gate

Let us consider the computational basis states defined as

uantum computation (QC) was first proposed by Benioff

[1] and Feynman [2] and further developed by a number

of scientists, e.g. Deutsch [3,4], Grover [5,6], Lloyd [7,8] and

others [9-11]. QC is the study of information processing tasks

that can be accomplished using quantum mechanical systems

[12]. It is based on sequences of unitary operations on the input

qubits using quantum gates [13, 14].The quantum gates have

been successfully demonstrated in the past using photonic

interference process [15,16].In photon-based optical QC

processes has been instructed to photonic interference

phenomena [17,18].This photonic interference or interaction

phenomena has been executed using different types of optical

device. There has been also works interesting the use of Beam

Splitter to perform the photonic interference or interaction [1922]. In optical approach the principle of photonic interference

or interaction operation is obtained by changing reflectivity of

Beam Splitter.

In this work, a set of beam splitter (BS) structures are

proposed and used to demonstrate the operation of a quantum

CNOT gate. The difficulty in optical quantum computing has

been in achieving the two photon interactions required for a

two qubit gate. This two photon interaction provide non-linear

operation which occurred in non-linear phase shift. To require

this non-linearity through two photon interaction is

accomplished using extra ―ancilla‖ photons. Vacuum state

input modes provide extra ―ancilla‖ photons. In quantum field

theory, the vacuum state is the quantum state with the lowest

possible energy. Generally, it contains no physical particles.

The design of CNOT gate has been simulated by OptiSystem

software where the directional coupler has been used as BS and

obtained that the BS based structure can be worked as a

quantum CNOT gate.

1

0

0

0

1

1

(0.1)

(0.2)

The CNOT gate acts on 2 qubits, one control qubit and another

target qubit. It performs the NOT operation on the target qubit

only when the control qubit is

1 , and leaves the target qubit

unchanged otherwise. Operation of CNOT gate is as follows:

00 00

01 01

10 11

11 10

The action of the CNOT gate expression will be written as [23,

24]

CNOT 00 00 01 01 10 11 11 10

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

20

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

1

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0

1 0 0 0

0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0

1 0 0 0

0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0

0 0 1 0

0 0 0 0

2

0 0 0

0 0 0

0 0 0

0 1 0

0 0 0

0 0 0

0 0 1

0 1 0

(0.3)

1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1

0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0

Fig. 1: A schematic of the Polarization of single photon mode. (A)

Horizontally Polarization, (B) Vertically Polarization, (c) Left Circular

Polarization, (d) Right Circular Polarization.

1

0

1 0 I 0 1 X

0

1

0 0 I 1 1 X

From equation (1.3) we can write the CNOT operator in matrix

form as:

U

CNOT

1

0

0

0

When input is

U CNOT

1

0

10

0

0

0 0 0

1 0 0

0 0 1

0 1 0

(0.4)

10 . So

0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0

1 1 11

0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1

0 1 0 0 1 1 1

Other operation is also performed this same way. So

U

CNOT

matrix acts as a CNOT operator.

2.2 Polarization state of Single photon as qubit

Let, Horizontal Polarization state of single photon be

defined as qubit

0 and Vertical Polarization state of single

photon is defined as qubit

1 . Superposition of these two

states can also form new polarization states such as Left

Circular Polarization (LCP), Right Circular Polarization

(RCP), etc.

Some polarization states are shown in fig. 1.

2.3 Splitter

A beam splitter is an optical device which can split an

incident light beam into two beams, which may or may not

have the same optical power. Half-silvered mirror, Nicol

prism, Wollaston prisms etc are also used to make beam

splitter. Waveguide beam splitters are used in photonic

integrated circuits. Any beam splitter may in principle also be

used for combining beams to a single beam. The output power

is then not necessarily the sum of input powers, and may

strongly depend on details like tiny path length differences,

since interference occurs. Such effects can of course not occur

e.g. when the different beams have different wavelengths or

polarization. The beam reflected from above does not require a

phase change while a beam reflected from below acquires a

phase change of and 50% beam splitter performs Hadamard

operation [25].

2.4 Half Wave Plate

A retardation plate that introduces a relative phase difference

of radians or 180 between the o- and e-waves is known as

a half-wave plate or half-wave retarded. It will invert the

handedness of circular or elliptical light, changing right to left

and vice versa. If relative phase difference between e- and owaves has changed then the state of polarization of the wave

must be changed [26]. When angle between optical axis and

0

incident light axis or light propagation axis is

450 then HWP is

acted as NOT operator [27].

2.5 Polarizing Beam Splitter

Polarizing Beam Splitter (PBS) divides the incident beam

0

into two orthogonally polarized beams at 90 to each other.

Output of the PBS, one is parallel to the incident beam and

other one is perpendicular to the incident beam. This two

divided beams obtain at two different faces of PBS. Actually

PBS is made by adding one transmittance and one reflectance

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

21

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

3

type polarizer. Sometime is called addition of a horizontal and

a vertical polarizer we got PBS means that PBS is a

combination of special type of a horizontal and a vertical

polarizer [28].

2.6 Dual rail technique

With dual rail the photon number is the same for all logical

states. The logical 0 is represented by a single photon

occupation of one mode with the other in the vacuum state

[29]. The logical 1 is the opposite of the logical 0 state with a

single photon in the other mode. This means that the logical

0 L equals the state 10 , while the logical one, 1

zero,

equals the state

Fig. 3: Conversion from polarization to spatial encoding.

L

The reverse process converts the spatial encoding back to

polarization encoding. To convert from polarization, to spatial

encoding and back, while preserving the quantum information,

it is required that the phase relationship between the two basis

components be preserved throughout: the path lengths must be

sub-wavelength stable (interferometric stability)[19].

01 .

Fig. 2: A simple principle sketch of a polarization beam splitter.

Dual rail logic is often implemented using the horizontal and

vertical polarization modes of a single spatial mode. In dual

rail logic encoding strategy the qubit is encoded in a pair of

complementary optical modes. If we want to represent n

qubits with this representation we will need N 2n ports and

n photons where in case of single rail logic N n ports and

n photons are needed [29]. Means that the logical

state

3.2 DESIGN METHODOLOGY of CNOT operation

The two paths used to encode the target qubit are mixed at a

50% reflecting beam splitter (BS) in fig.4 that performs the

Hadamard operation [21]. If the phase shift is not applied, the

second beam splitter (Hadamard) undoes the first, returning the

target qubit exactly the same state it started in (example of

classical interference).

00 L equals the number state 1010 and the logical state

11 L equals the number state 0101 [29].

Fig. 4: A possible realization of an optical quantum CNOT gate.

3 Design methodology

3.1Conversion from polarization to spatial encoding

It is most practical to prepare single photon qubits where the

quantum information is encoded in the polarization state.

H V 0 1 —polarization encoding,

where

H and V are the horizontal and vertical

i.e.

0 1 and 1 0 . When control qubit is 0 , then

phase shift is not applied and when control qubit is

1 , then

phase (π) shift is applied. So this phase shifting operation is

non-linear phase shift. A CNOT gate must implement this

phase shift when the control photon is in the ―

1 ‖ path,

otherwise not [21].

polarization states [19].

To convert from polarization to spatial encoding a

polarizing beam splitter (PBS) and half wave plate (HWP) is

used. In fig. 3, the HWP rotates the polarization of the lower

0

If π phase shift is applied i.e. non-classical interference is

occurred and target qubit is flipped, the NOT operation occurs,

0

beam to 90 when its optical axis is apt 45 to the beam.

After this rotation all components of the spatial qubits have the

same polarization state and they can interfere both classically

and non-classically.

3.3 Implementation of CNOT gate

In fig. 5 is shown a conceptual realization of CNOT gate

where the beam splitter reflectivity and asymmetric phase

shifts is indicated. Actually this gate is accurately given the

Non-linear operation by using two photon interactions and

performs CNOT gate operation [19]. From fig. 5 B1, B2, B3,

B4 and B5 are beam splitters (BS) and

vC and vT are vacuum

inputs. B1, B2, B3, B4 and B5 are assumed asymmetric in

phase. B1, B2 and B5 beam splitters have equal reflectivity of

Copyright © 2012 SciResPub.

22

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 1, Issue1, June-2012

ISSN 2278-7763

4

one third ( 1 3 ). B3 and B4 beam splitters have equal

reflectivity of 50:50 ( 1 2 ) [20].