Broken Houses: Science and Development in the African Savannahs

advertisement

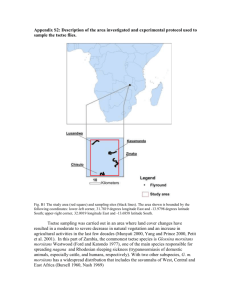

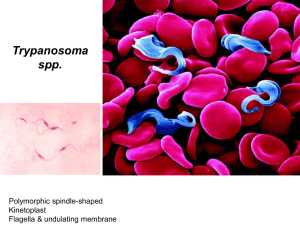

Broken Houses: Science and Development in the African Savannahs Brian Williams, Catherine Campbell, and Roy Williams Brian Williams in the director of an epidemiology unit that carries out research into the health and safety of South African mine workers. He has previously worked on the control of tsetse Dies aad trypanosomiasis in Kenya and on modelling vector borne diseases at Oxford University and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical medicine. Catherine Campbell has worked iB South Africa, as a clinical and social psychologist, in areas such as community health and social identity. She currently lectures in the Department of Social Psychology at the London School of Economics and Political Science and is collaborating with Brian Williams in a study of South African mineworkers' perceptions of health and illness Roy Williams is head of the South African Council for Higher Education, one of the oldest educational development non-government organizations in South Africa. His research interest is in the application of discourse theory to development issues. ABSTRACT In many developing countries people and livestock suffer from preventable or curable diseases, and their agriculture is vulnerable to natural disasters. A considerable amount-of technical aid is directed at alleviating these problems using modern science and technology, and yet most of these efforts either fail or even leave peasants and pastoralists worse offthan before. In this paper we consider some ofthe problems that arise in relation to development projects,focusing our attention on the savannah regions ofAfrica and, inparticular, on the control oftsetseflies, which are the vectors ofthe African trypanosomiases. called nagana in cattle and sleeping sic/cness in people. We present a detailed case study ofaprojectdesigned to enable aMaasai community inKenya to carry outtheir own tsetsefly control. We examine the complex setofrelationships andpowerstructures that mediate the actionsofthe players in development: scientists. local communities, governmental and nongovernmental institutions. and development agencies. The purpose ofthispaperis notto presentsolutions to complexanddifficultproblems butrather to raise questions thatshouldprovide aframeworkfor a debate concerning the role of science and technology in the development process. Me;tob;tayu enkaj; naar;ta enopeng - Once a house is broken it cannot be repaired. Maa Proverb Introduction Most people in the world live in poor housing with inadequate sanitation, are undernourished, and suffer from preventable diseases. Livestockand crops as well as people are regularly infected by viral, protozoan, and helminthic organisms that cause disease. Many of these parasites are transmitted indirectly by arthropod and other vectors that thrive in tropical and subtropical regions. Although substantial efforts have been made to address these problems using modern science and technology, many of them have failed 1-8 and therole of technical development, especially in Africa, remains controversial. In this paper we consider development projects in the savannah regions ofAfrica, which cover about two-thirds of the continent,9 that are intended to help pastoralists control the African trypanosomiases, diseases of cattle and people for which the tsetse fly (Glossina spp.) is the vector. Animal trypanosomiasis, or nagt1na, is carried by the savannah species of fly, mainly those belonging to the morsitans group, and occurs over most of Africa south of the Sahara and North of the Kalahari. Human trypanosomiasis, or sleeping sickness, is carried mainly by the forest and riverine flies of thefusea group and occurs inrellitively small foci. Here we present a case study of a project designed to enable a Maasai community in southwest Kenya to manage animal trypanosomiasis. This case 29 AGRICULTURE AND HUMAN VALUES - SPRING 1995 study highlights the way in which developmentprojects are nested within a complex set of relationships and power structures that mediate the actions ofthe players in the development drama: scientists,local communities, governmental and nongovernmental institutions, and development agencies. Why cows matter Cattle have been getting a bad press. Western editorials report increases in heart disease in humans due to the consumption of fatty red meat, the inefficient use of grain to fatten cattle, the generation of milk-lakes by . subsidized dairy farmers, and the greenhouse effects of methane produced by flatulent cattle and sheep.10 However, farmers in the arid and semiarid regions of the tropics and subtropics, where resources are scarce, the soil thin and marginal, and the rains unpredictable, have found a way to survive by keeping livestock. Settled stock-keepers live in small scattered groups because marginal lands will not support intensive, irrigated agriculture of the kind carried out in Europe. Nomadic herders move with the rains and the grazing opportunities and carefully husband their resources. On subsistence farms cattle supplement human muscle power by pulling plows and transporting surplus produce to market. Cattle consume resources that cannot otherwise be exploited: they eat grass and crop wastes rather than grain. Their dung is used as fuel, as building material, as fertilizer. Their milk is a major source ofprotein for children. Hides and surplus milk are sold to buy clothes and seed, to pay medical expenses and school fees. For pastoral people living in areas too dry for arable farming, cattle and small ruminants are essential. They are not only food, since blood and milk are the mainstay of the nomadic diet, but also money, since milk can be exchanged for vegetables, salt, and cloth, and animals are given as bride price. They are also a fmal insurance against disaster when they may be sold to buy available grain. 11 (See Solbrig and Young7 for a detailed analysis of pastoralism in the African savannahs.) The one thousand or so cattle breeds developed over the millennia have, like their owners, adapted to extremeclimates andpoor nutrition. They have evolved resistance to disease and are able to survive with little water. For these reasons cattle receive songs of praise as old as civilization. Trypanosomiasis: eradication or control? Perhaps the most debilitating diseases of livestock in Africa are the trypanosomiases caused by protozoan parasites that are spread among cattle and wild animal hosts by tsetse flies. Infected livestock develop fever, lose weight, andbecome weakand unproductive; breeding animals may abort or become infertile. Unless treated with drugs, many infected animals die of anemia, circulatory collapse, or inter-current bacterial 30 infections. 12 In areas where the tsetse challenge is low, the disease can be controlled by chemotherapy, but in areas of heavy drug usage, drug resistance is developing in the parasite populations and there is little prospect of new drugs being developed. It is estimated that trypanosomiasis excludes ruminant livestock from seven million square kilometers of otherwise suitable African range or farm land. After nearly one hundred years of research and control, which today costs several hundred million dollars per year, controlof the African trypanosomiases remains elusive. Although drug treatment and fly control have alleviated the worst ravages of human trypanosomiasis, serious outbreaks still occur in certain areas and animal trypanosomiasis remains prevalent over about 10 million square kilometers of Africa. Attempts to eradicate tsetse have generally been ineffective, damaging to the environment, or both. Eradication has failed, except in habitats marginal for tsetse survival or in countries, such as South Africa and Zimbabwe, that have substantial infrastructures,local expertise, and access to foreign exchange. In their pursuit of eradication, control workers have employed sophisticated and expensive technologies, the use of which cannot be sustained, to prevent reinvasion when donor funds dry up. A better strategy for managing trypanosomiasis is to control rather than eradicate the flies, and to employ chemotherapy to treat the few clinical cases of trypanosomiasis that still occur. In many parts of Africa, cattle have evolved a degree of resistance to trypanosomiasis. Whereas this "trypanotolerance" was once thought to be restricted to the shorthorn breeds, especially the N'Dama found in West Africa, recent evidence indicates that the Zebu l3 and Orma Boran l4 in East Africa and the white Zebu of the Fulani 15 in West Africa are also trypanotolerant, especially if they are well nourished. Most tsetse control projects have been conducted on a large scale, with little or no involvement of the affected communities in theirplanning orimplementation. Some local communities have been actively opposed to tsetse control, believing it to be a prelude to large-scale settlement in their area. l6 One of the primary beliefs of the scientists involved in the project described in this paper was that if trypanosomiasis is to be effectively controlled and managed in the long term, tsetse control policy will have to be based on the direct involvement of the local communities, that stock owners themselves must identify development priorities and be responsible for implementing and managing the programs in collaboration with the scientists. The Nguruman project Ten years ago scientists employed by the Kenya-based International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE) started a tsetse and trypanosomiasis re- Williams et al.: Broken Houses: Science and Development in the African Savannahs search program at Nguruman, which lies in the Rift Valley in southwestern Kenya close to the Tanzanian border. Approximately 6,000 people, mainly pastoral Maasai, live in the area on the Olkirimatian and Shompole Group Ranches, which cover about 850 km 2 • The ranches lie to the west ofLake Magadi and to the north of Lake Natron. Most of the area is semiarid range land but there are two small irrigation schemes, one at Nguruman and one atPaakase. During and after the rains, most families keep to the east of the Ewaso NgiroRiverbutas the dry seasonprogresses they move west across the river where the vegetation is thicker but the tsetse more numerous. If dry weather persists, they move to the base or the top of the Nguruman escarpment, areas set aside for emergency grazing, sometimes to other group ranches or even into Tanzania. Trypanosomiasis has been a severe problem over much of the area, and at times of drought, when the cattle are forced to graze in tsetse-infested woodland and thicket, the combination of nutritional stress and trypanosomiasis causes heavy livestock production losses and mortality. The scientists running the Nguruman project aimed to develop a method of controlling tsetse flies that could be carried out and sustained by people living in rural communities. Considerable effort was put into designing a trap that could be made by local people within their inkangitie (homesteads). This work led to the development of a series of "Nguruman" or "Ngu" traps.17 which are made from netting and blue and black cloth. To attract tsetse flies, the traps are baited with acetone and cow urine. IS The flies are trapped in a plastic bag. where they die from heat stress. No insecticide is used. Research over a period of eight years led to an understanding of the population dynamics of the flies and the epidemiology of the disease. 19. 20 Fly population dynamics were modeled to assess the density and distribution of traps needed to achieve a given level of contro1.2l , 22 The local community at Nguruman was involved in many aspects of the project throughout its duration. 23 Complementary studies were conducted to investigate the social structure and economic constraints of the community. In January 1987 a pilot tsetse control trial was started. The traps for this trial were made by people of the Olkirimatian group ranch in their inkangitie. In January of that year, 100 traps were distributed over 120 km 2 of the ranch. Later in the year. a further 100 traps were deployed. To assess the degree of control achieved, a few traps were set up to the north of the suppression zone to monitor the fly population there. Within eight months, catches in the suppression zone had fallen by 98-99% relative to catches in the comparison area. 24 In November, about two weeks after the rains had started, there was an invasion of flies from the nearby escarpment.24 The traps were sufficiently effective to rapidly reduce the fly numbers to their previous low levels. Despite repeated seasonal invasions between 1987 and 1990, fly density within the suppression zone was always kept below 10% of the fly density outside the suppression zone and at times fell as low as 0.1%. A sentinel herd of cattle kept within the suppression zone by staff of the Kenya Trypanosomiasis Research Institute acquired no trypanosome infections in 1988 and only a few in 1989, whereas cattle kept a few kilometers to the north of the suppression zone repeatedly became infected~d had to be treated with the curative drug Berenil 10-15 times per year,13 For tsetse control using traps to be economically viable, however, it was clear that control would have to be extended over the whole of the group ranch and surrounding areas. The Olkirimatian and Shompole Community Development Project (OSCDP) Given the technical success of the project in developing a cheap and effective trap together with a knowledge of the density of traps that would be required to control tsetse, it was now possible for the ranch members to carry out their own control of the flies. In 1990, the Olkirimatian Group Ranch Committee and other community members decided to apply the results of the research project and extend tsetse control to the whole of the group ranch. Because control per ae was outside the mandate of ICIPE, the group ranch committee established a community development project using Ngu traps to control tsetse and eliminate the threat of trypanosomiasis. The tsetse control was to be integrated with other development activities in the area. Ecotourism would be promoted to take advantage of the abundant wildlife. Small businesses, especially those run by women. would be encouraged to diversify sources of income and increase trade. A neighboring group ranch, Shompole, was brought into the project, enlarging the total area over which tsetse were being controlled to nearly l000km2•Thecommunities would set their own development priorities and local people wouldbe trained to implement such development themselves. In May 1991, the Olkirimatian and Shompole Community Development Project (OSCDP) was formed. Two British scientists, Robert Dransfield and Robert Brightwell, who had been responsible for the research project, acted as advisors. An economic analysis was made to ensme that tsetse control would be financially viable. One Ngu trap with odor baits costs about US$7.50 to make and operate for a year, excluding labor and transport costs for servicing. The high mobili~ of the most common tsetse species at Nguruman,2 Glossina pallidipes, allows a trapping mortality ratc of 4-6% per day to be im:qosed using only 2 trapsjkm2, costing S1S/year/ km . Infe$ed cattle at Nguruman are treated with Novidium , which costs about $2/cow/year. With a 31 AGRICULTURE AND HUMAN VALUES - SPRING 1995 2 generating schemes of the OSCDP project were beginstocking rate of about 30 cows/km , drug costs were ning to develop solid infrastructures and those responabout $60/year/km2 before the tsetse control started. sible were gaining experience and expertise. Several Thus, provided trap maintenance costs could be kept donor and extension agencies as well as nongovernmenbelow about $45/km2/year, trapping flies would not tal organizations were showing interest in the project only be cheaper than treating sickanimals with chemoCritical support was provided by the government of the therapeutic drugs, but would also increase productivNetherlands through the Kajiado Arid and Semi-Arid ity by improving animal health. In addition, effective Lands Development Program (ASAL). tsetse control would allow the pastoralists to graze their cattle in much-needed, formally tsetse-infested The only dark cloud over the project was the continued presence ofICIPE. Having been involved in dry season pasture. the early scientific stages of the project - but not in The local power structure of the group ranches is the OSCDP - ICIPE management believed it should dominated by traditional elites. 25 To involve the whole be in overall charge. However. despite the widespread community, a key objective of the project was to use of odor-baited tsetse technologies in other parts of mobilize and educate people on development issues, Africa, and their demonstrable efficacy at Nguruman. especially those related to land tenure, livestock disICIPE maintained that their use was premature. And ease control, and wildlife utilization. This process of despite the success of community-run tsetse control at empowering people could only be carried out by memNguruman, ICIPE stated that the Maasai community bers of the local community. The staff of the project was incapable of carrying out such an operation itself. formed a "focus" group, and were encouraged by the Attempts to reach a modus vivendi between the group advisors to attend workshops, seminars, and other meetings on pastoralist development issues. By 1993, ranch management committee and ICIPE failed. 26 project staff were conducting training and education There was interference with funding from donors. One donor expressed the opinion that ICIPE had "apparon tsetse control in the Maasai homesteads and funds ently declared total war against the project.,m Neverw~re being sought to extend this approach to broader theless. ICIPE continued to claim credit for OSCDP's development issues. With the support of the Kenya Wildlife Service, a successes.28 Ensuing events have been fully documented elsesuccessful community wildlife program was estabwhere. 26 A long series of disputes between the lished on the ranch. Four individuals, selected from each of the two ranches, were given intensive training Olkirimatian Group Ranch Committee and ICIPE culin wildlife tourism. They constructed offices from minated early in 1993 when group ranch members local materials, cleared campsites near water, and removed and returned the pilot control traps to ICIPE. However. with ICIPE's receipt of substantial Europrovided the sites with signposts, fireplaces, and rubpean Community (Be) funding for further tsetse rebish pits. A range ofbooldets and maps of the area were search,· certain elders of the group ranch were perproduced for sale and the tourist facilities were adversuaded to allow ICIPE to return and continue working tised in Nairobi. The local women formed a group to make headwork for sale both locally and in Nairobi. on the ranch. In the words of van Klinken27 • "ICIPE manipulated and divided the group ranch committees Having been excluded from access to education and decision making within the traditional Maasai power in order to bring the project under their control". As a result of these developments. three key OSCDP manstructures, most of the women on the ranches remain illiterate. The project therefore arranged for the Kenya agement staff resigned and the advisors were withdrawn by the donors. Ministry of Social Services to provide adult literacy classes for the women. All traps used in this development project were Success and failure made in the inkangitie. In the remote areas of the group In contrast to many earlier attempts at controlling ranches. a salaried team of four people deployed and tsetse by game destruction. bush clearing. and aerial maintained the traps and trained others in trap making. and ground spraying.29 many of which failed and none In the more accessible irrigated areas. traps were serof which were sustainable by local communities. the viced by members of the local community who were Nguruman Project established the feasibility of comprovided with bicycles and paid an honorarium from munity-run tsetse and trypanosomiasis control; the OSCDP made it a reality. For the first time. the knowlthe tourist revenue. By early 1993. the OSCDP was functioning well. edge, expertise. and technology were available to allow Tsetse flies were under control over much of the area: local communities affected by trypanosomiasis to cany their density was reduced by 97% in Ngurumani and out their own tsetse control operations if they so decide. populations were declining in other areas. The only And yet those donor organizations that should have exception was in Sampu. where ICIPE had continued the provided key support to the OSCDP at critical moments pilot control trial but had not maintained their traps. Here failed singularly to do so and the project has collapsed. tsetse numbers were on the increase. The various incomeThe OSCDP has been disbanded. the fliesareretuming to 32 Williams et al.: Broken Houses: Science and Development in the African Savannahs the areas in which they had beeneffectively controlled. In the brief account that follows we shall trace some of the reasons for the eventual collapse of the project to the implicit agendas and partisan interests of various groups resulting in an unseemly scramble to take over what remains of the project. The players The stakes in the development game involve billions of dollars and millions of lives. The players with money include the World Bank, the World Health Organization, and the governments of the United States, Europe, and Japan. The science ,and technology that underpin the development projects come largely from these countries. The players with the 'problems' include the governments of the Third World and the local government organizations that act as intermediaries between national governments and the people whose lives and conditions are to be improved. Within these countries are research institutions funded by industrialized countries, and those created as arms of the national governments. Finally, there are the peasants and pastoralists and urban poor who are the target of development. The World Bank The World Bank is one of the key players in the aid game and several analysts have pointed to the tensions that exist between the Bank's philanthropic goal of helping to eradicatepoverty and the economic constraints that face a commercial bank. 2. 30, 31 Thus, for example, the Bank advocates a "regime of law" to provide for "compulsory acquisition of animals in situations of drought and pressure" and "compulsory acquisition of land and movement of populations to facilitate private ranching and wildlife farming,,32 which are unlikely to be in the best interests of pastoralists and peasant farmers. The Uganda World Bank Livestock Services Projeci33 has budgeted $4.5 million for a "rolling eradication" of tsetse flies over thousands of square kilometers in western Uganda. This project neither considers how such an area is to be protected from reinvasion nor proposes community involvement or education, which we believe are essential prerequisites for successful, long term tsetse control. Hanlon34 comments on another set of tensions in the way in which the Bank operates noting that the Bank's frontline staffoften understand the needs of the poor, consult broadly and often see participation as important. But in the end it is "the hard men in Washington who negotiate in secret with top government officials and ministers on the framework agreement "who override all other agreements.',34 The Western and Japanese Governments Western governments and Japan make a substantial financial contribution to technical development projects. Yet reports abound of ambiguous outcomes of many of their development efforts. For example, the British Overseas Development Administration (ODA) claims that its multi-million-dollar tsetse project in Somalia in the late 1980s achieved local eradication. 3S Because the area covered by the program did not extend to natural tsetse barriers it is probable that the area has been reinvaded. The adverse social consequences of this eradication attempt may be difficult to reverse. After conducting detailed interviews among local farmers, an anthropologist employedby the ODA discovered that the local people were bitterly opposed to the project. Many of their chickens, which are an important part of their diet, had been killed by the initial spraying. In addition, the people were apprehensive that once the tsetse flies were gone, nomadic herdsmen would move livestock in and destroy their crops. In spite of the anthropolo~ist's findings, the ODA continued with the spraying S. Eventually, both cultivators and pastoralists lost. After tsetse were declared to have been eradicated, Mogadishu businessmen moved in, bought the land and obtained soft agricultural loans for its development. They then deforested parts of the area and used the loans for property development in Mogadishu.36 A project funded by the European Community has also failed to learn the lessons of this experience. About $30 million is being spent on the preparatory phase of a tsetse control project in the "common fly belt", which runs along the Z8mbezi between Zambia and Zimbabwe, and into Mozambique. and extends up the Luangwa Valley in eastern Zambia. In 1990 it was said that the "ultimate goal is to relieve the region of the constraint of animal trypanosomiasis by eradication of tsetse flies from the common fly-belt,,37 and the planned expenditure to achieve this end was reported to be in the vicinity of $300 million. The chances of eradicating the flies from 300,000 km2 of inaccessible. underpopulated land in countries where the extension services are almost nonexistent. are vanishingly small. In 1992 the plans for zambia became less ambitious and now "The final aim ... is the control of tsetse and trypanosomiasis in the Zambian part of the common fly belt which comprises 110,000 km2 , in which 1,200.000 people and about 700,000 cattle and goats are living." 3 Unless the EC adopts a community based strategy in those relatively restricted areas in which trypanosomiasis threatens cattle, the chances of achieving even this more limited goal are remote. The National Governments The governments of developing countries tend to view the pastoralist way of life as backward and incompatible with administrative goals such as tax collection, provision of health and education services. economic development. and promotion of national unity. S Hence sedentarization, subdivision of group 33 AGRICULTURE AND HUMAN VALUES - SPRING 1995 ranches, and irrigated agriculture are advocated rather than mobility and trade, even though the former are inimical to the ecology of semiarid lands. The group ranch system, adopted in Kenya after independence, left control of land and resources largely in the hands of the people living on the ranches. The Kenyan Government has decided to enforce the demarcation of the Olkirimatian and Shompole Group Ranches so that each piece of the ranch will be owned by one person. This can only lead to the destruction of the pastoral system, 7 which has functioned adequately until now, and, with the control of tsetse, could function well in the future. The Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) As First World donors despair at the prospects of encouraging effective rural development through centralized state bureaucracies, there is an increasing tendency to direct funds through nongovernmental organizations. These include the major world charities, but smaller NGOs are springing up all over the Third World to talce advantage of this new direction in which the money is flowing. Many NGOs are doing good work, but the disasters are now so many and so grave that much of their effort is talcen up with "fighting fires", and the prospects for long term, sustainable control of tropical diseases in livestock: and people are slight. The Research Institutions To make science more directly relevant to the needs and problems of the Third World, various research institutions have been created. Of particular note are those set up to promote agricultural research in Third World countries under the auspices of the Washington-based Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR).39 In addition there are a number of semi-autonomous institutions, such as ICIPE, and many national agricultural research systems (NARS) and universities in developing countries. The CGIAR centers represent the best of agricultural science that is carried out in the Third WorId. Their mission statement reads, "Through international research and related activities, and in partnership with national research systems, to contribute to sustainable improvements in the productivity of agriculture, forestry and fisheries in developing countries in ways that enhance nutrition and well-being, especially of low income people:,39 The quality of some oftheir work is high as judged from the standards of scientific rigor and precision and publications in international scientific journals. They have had a number of successes, particularly in relation to plant breeding and germplasm conservation. They take credit for introducing into India and Pakistan the semidwarf wheat varieties that resulted in the "Green Revolution" .39 But there is little mention in these reports of the adverse social 34 consequences of this revolution for poor peasants, the heavy reliance on fertilizers to sustain crops, or other long term implications that have raised doubts and fears in many people's minds. 40 Science has solved the problems; if the solutions create even greater problems in the future no doubt science will solve those also. The most important international livestock research institutes based in the Third World are the IntemationalLivestockCentreforAfrica (ILCA), based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and the International Laboratory for Research on Animal Diseases (IT..RAD) based in Nairobi, Kenya, both part of the CGIAR. The former carries out research on livestock production systems, the latter on immunology and molecular biology with the aim of developing vaccines to protect ruminant livestock against tick-borne diseases and trypanosomiasis. Although both institutes have made significant scientific advances, their research has done little to enhance the well-being of pastoralists and peasants. An appropriate and productive approach would be to work with local communities to identify key problems and needs before adopting a research strategy. Then, using all the tools modem science has to offer, science may contribute to raising the living standards of poor people. It might be determined, for example, that certain diseases were the most important production constraint in a given area and that these could best be controlled by vaccination; development of novel vaccines using molecular biology would then be appropriate. But developing new vaccines for the sake of using advanced technologies, however intellectually satisfying, will not, on its own, solve the problems faced by poor livestock farmers. The Scientists The scientists working at Nguruman believed that the failure of science to contribute to the control of tsetse flies in Africa stemmed from the fact that we were starting from the solutions and not from the problems. Molecular biologists are trained in Western universities in the techniques of polymerase chain reactions, monoclonal antibodies, and DNA sequencing. Since many students would like to use their skills to help others, they are set to work on projects that will help to alleviate the ravages of tropical disease. We know that in the West the development of vaccines has contributed greatly to the health ofourcitizenry•So we send them out to make vaccines against diseases of the tropics. Unfortunately, many tropical diseases, such as malaria, trypanosomiasis,leisbmaniasis, and theileriosis, are caused by protozoan organisms. Protozoa are not viruses. Theirlifecycles involve many distinct forms and stages, they are very variable and strain variation is the rule. We still do not have a subunit vaccine (one based on parasite molecules rather than whole parasites) that is effective against any protozoan organism. When we succeed, such vaccines are likely to confer only partial Williams et al.: Broken Houses: Science and Development in the African Savannahs protection for a limited time against some strains of the parasite. They are likely to cost more than most low income countries can afford. The Nguruman project took time and patience. The scientists had to get to know the people who live there and they had to get to know the scientists. The local community had to be engaged in the day-to-day practice of the research. It was necessary to build up a sound and reliable understanding of the ecology, entomology, and epidemiology of the flies and the disease. The scientists were willing to use whatever advanced science was needed - provided that it would contribute to the solution of the problem. The project succeeded in that it was possible to develop a method of controlling tsetse flies that was sustainableby the local people and was cost-effective in terms oftheireconomy and needs. Having successfully addressed the technical problems, the OSCDP was a natural development. It was not enough simply to control trypanosomiasis. Decisions would have to be made concerning the way in which the resulting increase in available grazing would be exploited, the impact this would have on the substantial community of wildlife in the area, who would pay for and who would benefit from the elimination of the major disease in the area. And the very success of the project brought with it many of the ensuing problems. Once the project was seen to succeed, many agencies and institutions wanted to control it in order to further their own interests, increase their own standing, and so enhance the flow of dollars through their institutes and organizations. Olkirimatian group ranch. The dams are designed to provide hydroelectric power. It has been suggested that water from the dams be used for large-scale irrigation. The most significant effect of the proposed developments will be to permanently inundate part of the downstream flood plain and stop seasonal flooding in the rest of it. This will destroy vital dry-season grazing. The environmental impact report notes that ..there would appear to be no practicable mitigating measures other than compensating for land affected in the flood plains,,41 which means buying off the relevant elites. It is interesting to contrast this treatment of pastoral livelihoods with the detailed and sympathetic attention the report gives to the flamingos and fish that breed in Lake Natron into which the Ewaso Ngiro river drains. The need to conserve the world's environmental resources is pressing. But we must be clear about how we shall do this. Somepeople argue that, by preventing overgrazing, the tsetse fly is the custodian of Africa's environment.42 One might as well argue that AIDS is the solution to Africa's population crisis. Nothing about crises improves an environment. People have many babies because many will die. Those that survive will keep you in old age. Nomads keep many cattle because drought and disease will kill most of them in the bad years. When drought and disease kill your children and your animals you produce more, not less. This is what any sensible person would do. The only way to limit the growth of animal and human populations is to offer people insurance against disease and drought and famine. The Development Specialists Many development specialists have years ofexperience at working on a particular problem in developing countries. But although these people may have great knowledge and experience in the control of a particular tropical disease, they are less often familiar with the host of related problems: political, social, and economic as well as problems of the environment, the ways in which communities will change and adapt to new situations, sometimes well, sometimes badly, in short to the consequences of their interventions in the complex and dynamic lives of Third World people. The BC is now planning tsetse control programs for Kenya and Tanzania. In early 1993, as part of this program, the BC gave ICIPE about US$7 million to work on tsetse ecology and trapping. Despite the fact that one ofthe main proposed research sites was within the OSCDP -where the communities were already successfully controlling the flies - none of the consultants sent to Kenya by the BC contacted anyone connected with the community control operations going on there. Knight, Piesold, and Partners, a British engineering firm, is engaged in the construction of a series of dams on the Ewaso Ngiro river, 30 km north of the The Local Communities Finally we arrive at the object of our compassion - the peasants and pastoralists. We classify them as poor people and regard them all the same. But what do the Maasai, the Luo, the Hausa, and the Zulu have in common? Their lives, their environments, their strategies for survival, and their cultures are as different as any in the world. At Nguruman, within a single Maasai clan, the people are grouped and bound in many ways: by age, sex, and parentage, by political affiliation, wealth, and employment. The groups change and shift with time. Sometimes they split. sometimes they merge. There are many sources of authority, some traditional some new. Understanding the nature of these relationships is difficult but acknowledging their complexity may prevent us from drawing facile conclusions. The successes and failures of the OSCDP depended in part on structures of power and authority within the groupranch25 that were not well understood by the scientists and outside advisors who worked there. The traditional elite within Maasai society is made up of those whose power is based primarily on relative wealth of cattle. With the advent of colonialism and subsequently of the modem state, other groups 35 AGRICULTURE AND HUMAN VALUES - SPRING 1995 gained influence, deriving their authority from education and political acuity. Political elites, drawn from the chiefs and other functionaries appointed by the colonial governments, were often recruited from the traditional elites. Now elected councilors need the backing of a political patron and tend to exploit differences between clans and between age-groups. Power and influence are gained by offering services to the dominant political patron, creating a class of leaders not accountable to the community. 25 The educated elite is drawn from an emerging class ofyoung, educatedMaasai, aspiring to escape the strictures and confines of traditional society, but their role is ambivalent. With communal land rights being replaced by individual land titles, the educated elite is provided with an opportunity to exploit their knowledge of the modern political economy to their advantage. The resultant land transfers are instigated and facilitated by the educated elite, who introduce land buyers from outside the district to their fellow Maasai, who may be persuaded to sell their land and so forfeit their future. 25 Now a new functional elite is emerging. These are members of the group ranches who, tired of being manipulated, want to take development into their own hands. They include youth groups pressing for educational opportunities, women's groups pressing to have their voices heard for the first time, and groups such as the management staff of the OSCDP. Independent of the other power elites, these groups are often small, isolated, and vulnerable and it was this weakness that enabled an outside body to manipulate and divide the group ranch committees.22 Science and development The authors believe that modern science and technology can make a significant contribution to alleviating the ravages ofdisease in the Third World, to increasing agricultural production and food security. However, each of the players in the science based development game is using science and technology to achieve their own ends and the consequences of development are often the opposite of what was intended. Perhaps the central contradiction is this. We are still locked into a reductionist world view deriving from nineteenth century science in which problems are reduced to a small number of parameters that we hope to understand and manipulate. Once we have identified what we believe is the key factor that gives rise to a certain problem, we manipulate or try to change it so as to achieve the desired end. This leads to the search for 'magic bullets' so that we have tried, and failed, to manage malaria first using insecticides, then using chemotherapy. Now all our efforts are being put into mosquito impregnated bed-nets; soon they will be put into vaccines. We did the same for trypanosomiasis. First it was game destruction, then bush-clearing, then 36 ground spraying and aerial spraying; now it is tsetse traps and targets. Ellis and Swift!! pointout that developmentpolicy in pastoral areas has sought to restore a supposed equilibrium to an area by destocking to the appropriate "carrying capacity" thus increasing livestock productivity. However, pastoral ecosystems are not in stable equilibrium but show cycles driven by abiotic factors; the carrying capacity is too variable for close population tracking. The evolution of pastoral systems that dominate agriculture in Africa's arid and semiarid regions is evidence of their viability. Ellis and Swift argue persuasively for development policies that build on pastoral strategies rather than constrain them, encouraging in particular those strategies that maintain livestock mobility and facilitate trade in livestock and their products. "Holistic resource management" ,43 a new idea to livestock scientists, is based on traditional pastoralist strategies. This advocates short periods of heavy livestock grazing and mobility of cattle. This strategy may be the best way to rehabilitate degraded range land and may bring about the "improved pastoralism" advocated by Kituyi. 44 Until the aid environment in developing countries is more conducive to adopting such relatively unpretentious, indigenous approaches, such strategies are unlikely to be implemented. The massive bureaucracies that dominate aid organizations, developmentorganizations, and research institutes presenta hostile environment for small, flexible, and community-based projects. The problem that we face is how to avoid the cooption of relatively powerless communities into narrowly dermed, inappropriate utilizations of technologies. The knowledge that modern science provides gives us great power - power that can be used in different ways by different people. While peasants and pastoralists have developed sophisticated strategies of their own for dealing with disease and drought and insect pests, modem science also has much to contribute. At Nguruman, the Maasai were able to keep cattle in the face of a high tsetse challenge. They did this by using trypanotolerant cattle, by moving their cattle seasonally to avoid contact with the flies when possible, making optimal use of the seasonal availability of grazing, and using chemotherapeutic drugs when necessary. Nevertheless, in very dry years, such as 1984, the combination of drought stress and trypanosomiasis led to the deaths of up to three-quarters of their cattle herd. Modem science made it possible to develop, with the local community, a method of tsetse control that was cheap, effective, and viable and led to the effective elimination of the disease from the ranch. But the most important aspect of this work may not have been the scientific achievement. It was that the Maasai now had a method of control that put power into their hands. As the fly numbers declined Williams etal.: Broken Houses: Science and Development in the African Savannahs and the threat of trypanosomiasis receded, they were able to take advantage of the new grazing and they could decide how best to do this. Questions If we cannot even decide what constitutes sound/ sustainable/appropriate development, if we cannot decide what we mean by community participation and appropriate technology, it will certainly be impossible to decide how to achieve these goals. The best that we can do is to end with a series of questions whose answers must precede anything that we do. • How do we educate all of the participants in the aid game? Not only the pastoralists but the bureaucrats of the World Bank, the civil servants in Washington and Brussels, the scientists, the experts, and the national governments? • How do we "empower" people when their societies are already structured and where some groups within already have power? How shall we empower the women without threatening the men? How shall we empower the youth without threatening the elders? Indeed, the very notion that "we" can empower "them" would seem to be a contradiction in terms. • How do we accelerate development when successful projects draw envy and greed and the desire for control from others with more money but fewer scruples than those we are trying to help? • Who should decide what the priorities are? Crops, livestock, sanitation, disease control, provision of infrastructures, industrialization? • How do we decide what constitutes a successful project? Whose interests shall we put first when we make such decisions? • How do we make outside parties accountable since their power and their security and their peer groups all lie without and beyond the communities on whom we bestow our aid? • How shall we begin to use science in ways that provide long term solutions to real problems rather than quick fixes to artificially conceived scenarios? The songs of praise that emanate from the North and the South, from the feedlots of Chicago and the semidesert scrub lands of Somalia, from those who eat too much and those who eat too little are very different. We must learn to recognize and accommodate the different songs that we sing when we advocate policies that affect the Hungry World. We must learn to understand the enduring relationship of people and cattle that has benefited both for thousands of years. If we respect and build on the hard-won life-styles of such people we might eventually arrive at development policies that help rather than hurt those at whom our aid is directed. Acknowledgments We thank Asteir Alrnedorn, Robert Brightwell, Steven Chown, Felicity Cutts, Robert Dransfield. Karolein Fonck, Sophy Fonnan, Jo Lines, Kelly Lee, Judith Locke,PhilipMcDowell,SusanMacMillan,IanMaudlin, Martin Odiit, Michael Packer, Timothy Robinson, Elaine Sharland, Antje van Roeden, CharI Walters, Gavin Williams, and William Wint for comments on this manuscript, some critical. Responsibility for the resulting article rests entirely with the autIIori References 1. Hancock, G. The Lords ofPoverty London: MacMillan, 1989,p.42. 2. Gnaegy, S. and J. R. Anderson, editors, Agricultural Technology in Sub-8aharan Africa: A Workshop on Research Issues. Urbana-Champaign: University of Dlinois Press, 1991. Cited in lNTBRPAKS (International Program for AgricultuIal Knowledge Systems), 8 (No.2 1991): p. 4. 3. World Bank. Kenya Bura Irrigation Settlement Project. Project Completion Report. CR. 722-KP/LN. 1449KB. World Bank. AgricultuIal Operations Division, Eastern Africa Department (July 31, 1989).. 4. Desowitz, R. The Malaria Capers: More Tales ofParasites, People, Research and Reality. New York: W. Norton, 1991, pp. 275-276. 5.Cheru,F. "StructuIalAdjustment, primary resomcetrade and sustainable development in sub-saharan Africa." World Development 20 (1992). 6. Zerihun, T.RuralDevelopmentSchemes:A Comparative StudyoftheAwashValleySettlementSchemesinEthiopia and the Gezira Settlement Scheme in the Sudan. MS. Thesis. Uppsala: Swedish Univmity of AgricultuIalSciences, 1983.DiscussedinF. ChenJ, "Structural Adjustment, primary resource trade and sustainable development in sub-saharan Africa." World Development 20 (1992). 7. Solbrig, O. T. andM D. Young. "Toward a sustainable and equitable future for savannahs." Environment 34 (1992): 7-35. 8. Bekure, S., N. De Leeuw, B. E. Grandin. and P. J. H. Neate, (editors). "Maasai belding. An analysis of the livestock production system of Maasai pastoralists in eastern Kajiado District, Kenya." ILeA SystemsStudy 4. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: R..CA Press, 1991. 9. Huntley, B. I. and B. H. Walker. Ecology of Tropical Savannahs Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1982. Cited by C. H. Scholtz and S. L. Chown. "Insect conservation and extensive agriculture: The savannah of southern Africa." InPerspectivesonInsectConservation edired by K. J. Gaston, T. R. New, and M. J. Samways, to be published. 10. Kleiner,K. "Methanesniffermonitorsbovinebelchers." New Scientist 7 May, 1994,p. 14. 11. Ellis, I. and D. M Swift. "Stability of African pastoral ecosystems: Alternate paradigms and implications for development" Journal of Range Management 41 (1988): 450459. 37 AGRICULTURE AND HUMAN VALVES - SPRING 1995 12. Williams, B. G.,R D. Dransfield.R Brightwell, and D. J. Rogers. ''Trypanosomiasis: Where are we now?" Health Policy and Planning 8 (1993): 85-93. 13. P. Stevenson, personal communication. 14. Dolan,R B.,AR Njogu,P.D. Sayer,G. Qkech,andII. Alushula. ''TrypanotoleranceinEastAfrica: TheOnna Boran breeding and selection programme:' Proceedings of the Nineteenth Meeting of the International Scientific Council for Trypanosomiasis Research and Control. Lome, Togo, 30 March - 3 April 1987. QAUI SlRC (1988). 15. W. Wint, personal communication. 16. UNDP Report ofEvaluation Mission on Tsetse Control toAssistMigratoryPastoralists URT/86/0 141NO 1/12, 1990. 17. Brightwell, R, R. D. Dransfield, C. A KyOIku, T. K. Golder, S. A Tarimo, and D Mungai. "A new trap for Glassina pallidipes." Tropical Pest Management 33 (1987): 151-159. 18. Dransfield,R D.,R Brightwell, M. F.Chaudhury,T.F. Golder, and S. A. R Tarimo.. "The use of odour attractants for sampling Glossina pallidipes Austen (Diptera: Glossinidae) at Nguruman, south-western Kenya" BulletinofEntomologicalResearch76 (1986): 607-619. 19. Williams, B. G., R D. Dransfield, and R Brightwell. "Tsetse fly (Diptera: Glossinidae) population dynamics and the estimation of mortality rates from life-table data" Bulletin ofEntomological Research 80 (1990): 479-485. 20. Brightwell, R, RD. Dransfield, and B. G. Williams. "Factors affecting seasonal dispersal of the tsetse flies Glossina pallidipes and G. longipennis (Diptera: Glossinidae) atNguruman, south-westKenya" Bulletin ofEntomological Research 82 (1992): 167-182. 21. Dransfield, R D. and R Brightwell. "Problems of field testing theoretical models: acase study." Annales de la Societ~ beIge de Medecine tropicale 69 Supplement 1 (1989): 147-154. 22. Williams, B. G., R D. Dransfield, and R Brightwell. "The control of tsetse flies in relation to fly movement and trapping efficiency." Journal of Applied Ecology 29 (1992): 163-179. 23. Dransfield, RD., B. G. Williams, and R Brightwell. "Tsetse and trypanosomiasis control: Mythorreality?" Parasitology Today 7 (1991): 287-291. 24. Dransfield, RD., R Brightwell, C. Kyorku, and B. G. Williams. "Control of tsetse populations using traps at Nguruman, south west Kenya" Bulletin of Entomological Research 80 (1990): 265-276. 25. van Klinken, M K. "Maasai pastoralists in Kajiado (Kenya): Taking the future intotheirownhands."Paper presentedatthejointIWGIA-eDRconferenceon"The question of indigenous peoples in Africa," June 1-3, 1993, Copenhagen, Denmark. 26. Dransfield. R D. and R Brightwell. ProjectReport on the Olkirimatian and Shompole Community Develop38 mentProject. (1993) Copies available on request from the present authors. 27. van Klinken, M K. Letter to Director SNV/Kenya, 11 November, 1991. 28. Anonymous. "Nguruman: Amodelforintegrated vector management" Dudu 42 (1992): 4-5. 29. Ford, J. The role of the trypanosomiases in African Ecology: A study of the tsetse fly problem. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971. 30. Culpeper, R "With Lewis Preston at the helm, whither the World Bank.?" Ceres March-April 140 (1993): 6. 31. Williams, G. P. "The World Bank, population control and the African environment" South African Sociological Review 2 (1992): 2-29. 32. World Bank. "Land use and land tenure systems in the arid and semi-arid lands of Kenya: The state of the art andpolicy options." Compositereportpreparedfor the ASAL Team of the World Bank's Resident Mission in Eastern Africa, May, 1993. 33. World Bank. The Uganda WorldBankLivestockServices Project. Project Proposal, August, 1990. 34. Hanlon,J."CanSouthAfricaridetheIMFTiger?"AFRA News (June 1993): 14-15. 35. Clarke, S. E. "The war against tsetse: Tsetse fly eradication along the Shebelle Rivex, Somalia" Rural Development in Practice 2 (1990): 17-19. 36. Campbell, D. "Businessmen destroy Somali forests." FarmAfrica (August 1989): 5. 37. Proposalfor a three-year extension ofthe preparatory phase of the EC funded regional tsetse and trypanosomiasis control programme (RITCP) of Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Prepared by the Office of the Regional Co-ordinator, RTTCP, Harare, Zimbabwe on behalf of the Regional Standing Cornmitteefor theRTTCP. December, 1990. 38. Regional Tsetse and Trypanosomiasis Control Project zambia. Prqmata:y w<Jk on a Land Use Planning Unit (Lupu).Fmalmi&Ulrepcrt.November,I992.Prepared by II. G. A vanPanhuys,~undPartnecConsu1lants GmbH.Frnnkfurter S~ 63-69, D 6236, Eschlxm 1. 39. Plucknett. D. L. "International agricultural research for the next century:' Bioscience 43 (1993): 432. 40. van Wijk.J. "VandanaShivaexplores 'The Violence of the Green Revolution':' Biotechnology and DevelopmentMonitor 11 (June 1992): 24. 41. Kenya Power Company EwasoNgiro (South) Multipurpose Project: Environmental AssessmentStage IIIReports. Nairobi: Knight Piesold and Partners, 1993. 42. Onnexod, W. E. "A critical study of the policy of tsetse eradication." Land Use Policy 3 (1986): 85-99. 43. Savory, A. Holistic Resource Management. Washington, DC: Island Press, 1989. 44. Kituyi, M. "Land utilization in Kajiado: Some reflections and policy suggestions." In Proceedings of the Second Conference on the Future ofMaasai Pastoralists in Kajiado District (Kenya), van Klinken, editor, Kajiado: Kenya, ASAL, 1991.