Farmland Biodiversity Measures to create and enhance farmed habitats

advertisement

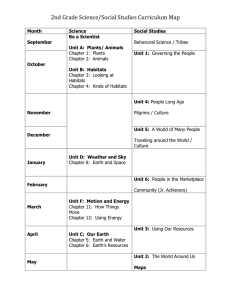

Farmland Biodiversity Measures to create and enhance farmed habitats Farmland Biodiversity Measures to create and enhance farmed habitats Caitríona Carlin and Mike Gormally Applied Ecology Unit, NUI Galway and Daire Ó’hUallacháin and John Finn Environment Research Centre, Johnstown Castle, Teagasc 2010 Table of Contents Page Introduction How to use this guide 4 Part 1 5 Part 2 Part 3 How to manage commonly occurring habitats on the farm Hedgerows, stone walls and earth banks 6 Wet ditches and drains 9 How to create new habitats on the farm 11 Creating ponds, puddles and scrapes 12 Creating woody habitats in orchards Creating log piles 14 15 How to maintain special habitats on the farm 16 Dry grasslands 17 Wet grasslands 19 Semi-improved grasslands 21 Blanket bogs 23 Turloughs 25 Fens 27 Acknowledgements 29 Sources of additional information 30 Selected bibliography 31 GC CS MSS 4 Introduction What is this guide? This guide aims to (1) raise awareness of ecological features on farmland, (2) explain why they are important and (3) demonstrates how they could be managed to help wildlife. This guide is not a detailed habitat management manual. Additional sources of information such as selected bibliography and weblinks are provided. Please consult with National Parks and Wildlife Service when considering work on specially protected sites. Who is it for? This guide is aimed at farmers and all people involved in providing advice on managing land. Why is this guide needed? Some of Ireland’s best-known wildlife require farmland. Bumblebees, bats and barn owls rely on farm practices to provide them with shelter and food. Plants and animals have been able to exploit different parts of the farmed countryside, such as dry stone walls and earth banks, hedgerows, trees, woodland belts and copses, wet ditches and ponds. Many species need a mosaic of different habitats: for example, some beetles like to overwinter in grass tussocks, but bare ground can also be important for basking. A number of scientific papers have been published which describe the ecology of different habitats and how the species found within them are influenced by management, including farming practices. Some of this information, which has been generally unavailable to farmers, is presented in this guide. How to use this guide? This guide will help to identify important wildlife features on a farm. It is divided into 3 key sections, each with relevant images. Part 1: How to manage commonly occurring habitats on the farm Part 2: How to create new habitats on the farm Part 3: How to maintain special habitats on the farm This guide is compact and designed to be taken out and used around the farm. It aids visual recognition of key features that are good for wildlife and suggests a variety of steps to benefit farmland habitats. Part 1 Commonly occurring habitats on the farm 6 Field Boundaries Dry stone wall Hedgerow CS Hedgerows and tree-lines are features in the landscape. Tree-lines mainly comprise mature trees whereas hedgerows mostly consist of shrubs. Timber should not be extracted from the treeline. Dead and decaying wood should be left in situ. Retain a margin to ensure spray drift and fertiliser does not reach the hedge. Woodland belt DB Stone walls are man-made DB structures which vary in their age, geology, construction style and thickness. Walls can support a wide variety of wildlife such as lichens, mosses and ferns. Some invertebrates and lizards bask on south facing walls, whereas hedgehogs and smooth newts may hibernate within thick stone walls. Woodland belts can be small islands of seminatural habitats within the farmed landscape. Native trees should be dominant, with an abundant understorey. Timber should not be extracted from the woodland. All dead and decaying wood should be left in situ. Allow scrub to develop around the margins. Hedgerows and tree-lines Hedgerows were planted as boundary features. Typically they consist of shrubby trees such as Hawthorn, Hazel, Guelder Rose, Dog Rose, Blackthorn, Holly and Bramble. 7 Hedgerow plants Plant a variety of shrubs to provide food or shelter to wildlife during the year. Honeysuckle •Leave uncut during the winter to provide berries for birds. Cut between January and February. No cutting can take place between March 1st- August 31st. •Cut about one-fifth of the hedge at least once in a three year cycle. •Typically hedges that are higher, wider and bushier at the base are better for wildlife. Sidetrim the hedgerow to about 1.5m high, forming an A shaped profile which helps thicken the hedge. •Retain a margin adjacent the hedgerow. Hawthorn Guelder Rose Dog Rose Hedgerows require management. This hedgerow has become overgrown because it has not been managed. The hedgerow has “escaped” and is becoming a tree-line. Reinstate gappy hedges by planting up the gaps or lay the old hedge. Stone walls and earth banks Common Blue Damselfly Common Grasshopper Spleenwort in wall crevice Earth banks Wild Strawberry 8 Features to maintain •Retain stone walls where present. Repair stone walls where necessary. •Maintain local techniques and styles of wall construction. •Walls may support lichens, ferns and mosses. Don’t remove vegetation. •Take care when spreading slurry to ensure that no slurry drift reaches the wall. •Remove Ivy if the wall becomes unsteady. •Do not paint dry-stone walls. Features to manage Earth banks are wide grassy margins which contain a variety of plants, and may contain scrubby trees, shrubs and occasional stones. Grassy bank with Birdsfoot Trefoil •Do not apply herbicide or pesticide. •Do not deposit waste on the earth bank and remove any dumped rubbish. •Cut once a year in the late summer to allow grasses and flowers to set seed. •Take care to avoid the accidental spillage of slurry or manure. 9 Wet ditches and drains Features to note Wet ditches and drains were once dug to drain waterlogged soils and assist with the intensification of farming practices. However, ditches nowadays frequently receive little maintenance and often retain species characteristic of wetland habitats. Key features are shallow edges with some bare mud, sloping banks and a varied depth. The extent of vegetation present should vary, from very little to abundant. Features to manage •If drains become silted up, a dredging programme may need to be instigated on a four year rotation. •Identify an area of low biodiversity value for spoil deposits before dredging begins. •Undertake dredging in the autumn to minimise impacts on amphibians and invertebrates. •Do not clear the whole drain at the same time. Damselfly beside Starwort Water Snail feeding Marsh Marigold Wet ditches and drains (continued) 10 Features to maintain •Maintain species richness by mowing or cutting opposite sections in a threefour year rotation. This removes fast growing species and allow slower growing species to mature. •A cut twice a year retains more plant species than mowing once, never, or every alternate year. •Leave cut vegetation on the bank overnight to allow invertebrates and amphibians return to the drain. •Best practice maintenance is to work from one side of the bank only, in small sections, leaving at least some sections unmanaged in each phase of rotation. •A spring cut may benefit vegetation but late cuts at the end of the summer or during the autumn are often recommended for birds e.g. Reed Bunting. Features to enhance •If drains begin to dry out, drains may be allowed to silt up or sluices may be erected to retain ditch habitats. Features to enhance •Fencing may be required, but fence installation should allow for occasional controlled access by cattle to graze bankside vegetation, and open up bare ground through a small amount of poaching. •During the Autumn, depth can be varied by removing a small section of the bank to create a shallow shelf along the edge of the drain. This shelf, called a berm, alters the slope and increases the surface area of the bank, allows for fluctuating water levels and creates sheltered habitats for amphibians and invertebrates. Cattle access may naturally create a berm, or machinery may be used to build it. Water Mint Large Red Damselfly Water Avens Part 2 Creating new habitats on the farm KS Farm ponds, puddles and scrapes 12 Ponds are usually small bodies of standing water, surrounded by and containing vegetation, muddy bays of bare ground, many invertebrates and are used by a wide variety of birds, amphibians and mammals. Features to note •an irregular shape •shallow depth •deep in one section only •partly in shade, partly in sun •Small muddy scrapes located nearby Ponds with high biodiversity value are often sited in natural hollows, close to remnants of other habitats such as treelines, earthen banks, hedgerows, orchards. Ponds close to one another form a network of ponds in the landscape. Different sizes increase the variety of wildlife. Choosing the location of a pond •Pond water quality is important in deciding where to locate a network of ponds in the landscape. Do not locate ponds where they will be subject to runoff from intensive farmland. Ponds should be fed by clean water, that is, water that runs off deciduous woodland, old pastures and other semi-natural or conservation habitats. •Do not dig out or deepen existing wet areas as they often have their own wildlife value. This includes marshes, reedswamps, reedbeds, muddy scrapes and wet grassland. Mayfly Frog in breeding condition: male has a blue chin. Damselfly near Gypsywort Farm ponds, puddles and scrapes (continued) Diving Beetle Smooth Newt 13 Pond Skater Features to manage and maintain This is general guidance only. More advice and detailed instructions are provided by Pond Conservation Trust (see further information). Timing factors •When to dig the pond depends on the location and impacts on other wildlife. •The best time to create ponds is in autumn. •Avoid creating ponds in very wet weather. Heavy machinery can damage the soil structure. •The best shape is a slightly irregular kidney bean shape as this creates small sheltered bays. •Whether a liner is used or not, ensure there is a substrate to which plants can attach. •Over time, plants will colonise the pond, but the process can be speeded up by carefully selecting a few native plants from a nearby pond. It is unlikely that plants from garden centres are native and therefore must be avoided. •Plant trees to the north of the pond, some way back to ensure leaves cannot clog up the pond. • Clean out each pond in a phased three-four year rotation. If too much silt is a problem, remove silt between September – November. Clear unwanted leaf litter at the same time. Plant thinning can be done in the first 6 months of the year. In summer, remove excessive duckweed. Dispose of unwanted material away from the pond. Features to enhance •If space allows, create a number of ponds at different times to maintain pond vegetation at different age structures. •If a pond is large enough, some access could be given to cattle to allow a little poaching and disturbance, but this would only be for limited periods of time to prevent the pond becoming turbid. •Locate ponds close to field boundaries such as tree-lines, hedgerows, field banks, and woodland to avoid farm traffic. Maintain a buffer zone around the pond to protect the habitats within 50m of the pond. •Excavate shallow scrapes with slowly receding water levels close to an existing pond to benefit invertebrates and birds. Woody habitats and orchards 14 Features to note Old orchards have the potential to become biodiversity hotspots, comprising a range of habitats such as dead or decaying wood, species rich grassland and hedgerows and stone walls. Stone wall Decaying wood Apple blossom Orchard trees support lichens, mosses, fungi and beetles and provide food for many birds, mammals and pollinators. Features to manage •A diverse ground flora can be maintained within orchards by traditional grazing or mowing practices. Green Veined White Butterfly on Dandelion seedhead with other ground flora such as Wood Violets, Barren Strawberry and Bluebells. Features to enhance •Plant new fruit trees to ensure the future of orchard habitats. •Plant a flower-rich border adjacent to the orchard to attract bees; use native wildflowers if possible. •Retain standing dead wood. Splits and holes provide shelter for bats and birds. Standing wood Log piles and other woody habitats 15 Features to note •Log piles can support moss, lichens and other flora and are used as an overwintering site by amphibians, Hedgehogs and some invertebrates. A south facing slope provides basking areas for Common Lizards, so keep brambles cut back. Log piles in shady spots are useful for many invertebrate species. Features to create •Stack cut timber to form log piles in a variety of frost-free locations, facing south, west and east to maximise basking opportunities for invertebrates and Common Lizards. •Create dedicated spaces for invertebrates by filling wood pallets with hay, straw, rough cut wood logs, and dried umbellifer stalks. •Drill holes into some of the logs to create additional over-wintering spaces. •Place log piles beside ponds to provide suitable hibernation sites for amphibians and invertebrates. Features to enhance •Include living plants like Ivy, Clematis and Honeysuckle in a logpile, as well as dead stalks and dry seed heads to attract bees or butterflies and mammals. KS •Leave decaying wood in situ. To enhance wet wood wildlife, place decaying wood in and close to nearby ponds. •Fungi and wood eating invertebrates will colonise rotting wood. Place rotting timber in shade to form a decaying wood microhabitat. Part 3 Special habitats on the farm