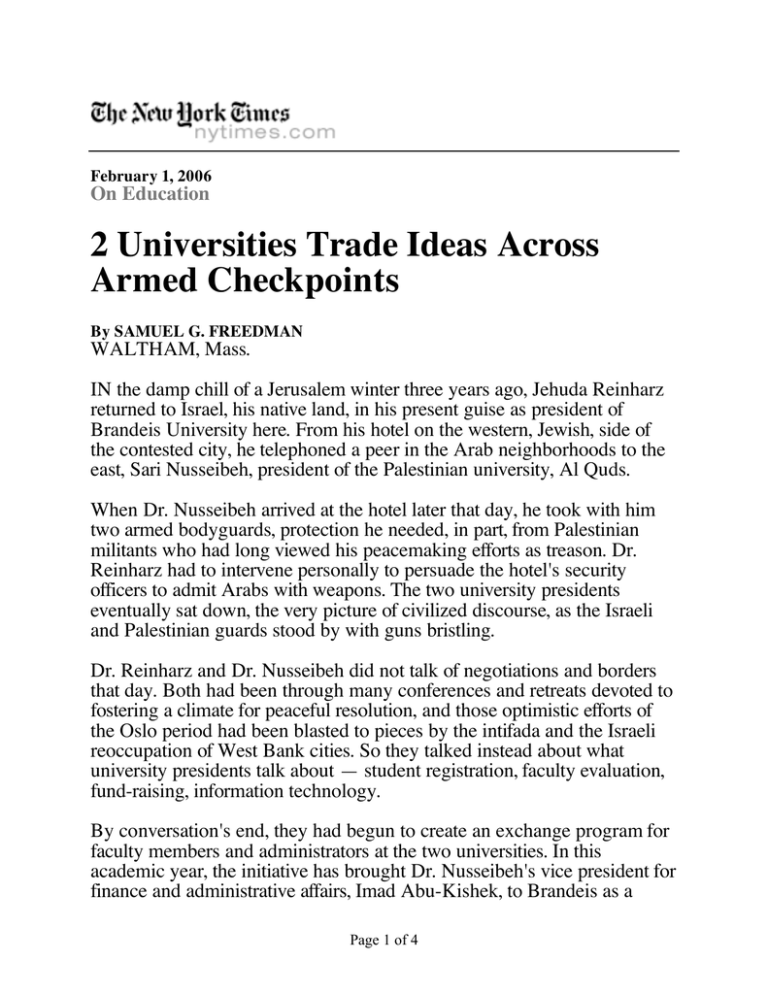

2 Universities Trade Ideas Across Armed Checkpoints

advertisement

February 1, 2006 On Education 2 Universities Trade Ideas Across Armed Checkpoints By SAMUEL G. FREEDMAN WALTHAM, Mass. IN the damp chill of a Jerusalem winter three years ago, Jehuda Reinharz returned to Israel, his native land, in his present guise as president of Brandeis University here. From his hotel on the western, Jewish, side of the contested city, he telephoned a peer in the Arab neighborhoods to the east, Sari Nusseibeh, president of the Palestinian university, Al Quds. When Dr. Nusseibeh arrived at the hotel later that day, he took with him two armed bodyguards, protection he needed, in part, from Palestinian militants who had long viewed his peacemaking efforts as treason. Dr. Reinharz had to intervene personally to persuade the hotel's security officers to admit Arabs with weapons. The two university presidents eventually sat down, the very picture of civilized discourse, as the Israeli and Palestinian guards stood by with guns bristling. Dr. Reinharz and Dr. Nusseibeh did not talk of negotiations and borders that day. Both had been through many conferences and retreats devoted to fostering a climate for peaceful resolution, and those optimistic efforts of the Oslo period had been blasted to pieces by the intifada and the Israeli reoccupation of West Bank cities. So they talked instead about what university presidents talk about — student registration, faculty evaluation, fund-raising, information technology. By conversation's end, they had begun to create an exchange program for faculty members and administrators at the two universities. In this academic year, the initiative has brought Dr. Nusseibeh's vice president for finance and administrative affairs, Imad Abu-Kishek, to Brandeis as a Page 1 of 4 senior management fellow. There he has spent his days delving into the intricacies of departmental budgeting, employee benefits packages and the like, as well as taking graduate courses in strategic management, leadership and organizational behavior. Later this spring, a delegation of Al Quds middle managers from areas like human resources and accounting will visit Brandeis for a week. The program has received nearly $700,000 in two grants from the Ford Foundation. Officially, Mr. Abu-Kishek's role is to develop his university's "administrative capacity." Practically, the result of his residency here might be called peacemaking by indirection, a version of coexistence training so ordinary it is audacious. "The two approaches are not mutually exclusive," Dr. Nusseibeh said in a telephone interview from his office in Jerusalem. "When you speak professionally, you will find many layers of possible agreement. If you bring people together to discuss microbiology or math or public health, as a byproduct you are addressing the surrounding issues." Over lunch in Brandeis's faculty club last week, Dr. Reinharz expressed a similar lack of sentimentality. "My aim is not to change the world because I know I cannot change it," he said. "We want to provide a nonpolitical, nonconference, nondemonstrative way to make an impact." IN certain respects, the two universities are surprisingly comparable. Both were created in the recent past, Brandeis in 1948 and Al Quds through the merger of four smaller colleges in 1995. The enrollments stand close, 4,000 at Brandeis and 6,000 at Al Quds. Each institution serves as an emblem of communal identity and aspiration, Brandeis for American Jews, Al Quds for Palestinians. Which, of course, goes right to the utter improbability of this partnership. Of necessity, Al Quds has perfected the art of crisis management. Between 1995 and 2000, as the Palestinian Authority served as the funnel for financial support to Al Quds from the European Union, faculty members and administrators sometimes went months without being paid. When Israel largely closed its borders to Palestinians during the second intifada to try to halt terrorist attacks, many Al Quds students could not afford Page 2 of 4 tuition because they or their parents were barred from traveling to jobs inside Israel. Only a bail-out package by the Arab Bank in Saudi Arabia saved the university from closing altogether. The separation barrier being constructed now between Israel and the West Bank will ultimately leave Al Quds campuses in Ramallah and Abu Dis on one side and the East Jerusalem campus and administrative headquarters on the other. Mr. Abu-Kishek's daily commuting from his home in Ramallah to his office in Abu Dis takes him through the Kalandia checkpoint, which might process him in as little as 15 minutes or take as long as two hours. Dr. Nusseibeh, while facing death threats from Palestinian militants, has also been detained by Israeli authorities for two brief periods in the past 15 years. Amid all the turmoil, from both without and within Palestinian society, Al Quds has managed to more than triple its enrollment since its founding and to cobble together an annual budget of $20 million. Its programs in computer science, engineering, public health and nursing are considered particularly substantial. Still, it has no dormitories, no student center, no full-time fund-raiser and virtually no endowment. Fully 60 percent of its annual budget goes straight into salaries for the faculty and staff. In contrast, Brandeis has an endowment of $570 million and an annual budget of $263 million, only one-third of which flows into salaries and benefits. "When you build something in a hurry, you need to fix it," said Mr. AbuKishek, 40, who has a bachelor's degree in electrical engineering and a master's in political science. "We have no organization in the modern way. We depend on the relationships of the president. We try to find out who has connections where. Now we need a better strategy to solve our financial problem." With an engineer's appreciation of detail, Mr. Abu-Kishek has been studying the way Brandeis allows each department to devise its own budget; how it handles both salaries and benefits as part of human resources; lumps together functions from registration to social activities under one student-affairs office; and has merged its library and information-technology operations. None of this may sound especially sexy, but these are the organ systems of a university, the throb of life Page 3 of 4 beneath the epidermis. The influence, though, runs both ways. Several groups of Brandeis faculty members and administrators have visited Al Quds, coming away especially impressed with the university's "web of relationships in the community, its role in civil society," as Daniel Terris, a professor who helps lead the exchange program, put it. After Hamas's victory in the Palestinian elections last week, the degree of civility in Palestinian society, particularly regarding contacts with Israeli and American Jews, will surely be tested. Having received steady criticism for the collaboration with Brandeis since it began, Dr. Nusseibeh predicted that "the pressure will be building" under a government led by a group sworn to Israel's destruction. "It wasn't optimism that made us kick this off," Dr. Nusseibeh said. "It was an act of faith in building the future. That commitment has remained through difficult periods before. If we'd worked only as optimists, we would've given up." E-mail: sgfreedman@nytimes.com Page 4 of 4