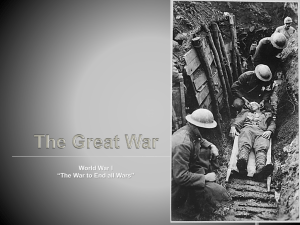

T THE E OU TBR

advertisement

THE T E OUTBR REAK K OF F THE FIIRST T WOR W RLD WAR R–L LESS SONS FO OR LEA L DER RS TO ODA AY JON J C CHAPM MAN, VISITI V ING FELLOW W, TH HE PRA AXIS CENTR C RE On O 28th Ju une 1914 – one hun ndred yearrs ago – th he Austria an heir to tthe throne e, Archdukke Ferdinand, F was assassinated by b Serbian nationalistts in Saraje evo. This set in train n the eventts that led up p to the decclaration of o war betw ween the major m powe ers of Euroope and fo our years of o unprecede u nted slaug ghter. At A the end of the warr the British Empire w was cripple ed, Germa an ambitionn to domin nate Europ pe had h been tthwarted, France ha ad lost a g eneration of young men m and R Russia had d collapse ed before b eme erging as a commun nist state. The Austtro-Hungarrian and O Ottoman Empires ha ad simply s disa appeared off o the map p. In terms off leadership, the care eers of the e men who o led Europ pe into warr did not survive to itts conclusion c . Only O the U United Sta ates, led by b Woodro ow Wilson,, emerged d stronger and more e confident, although a nowhere wa as there any a appetitte for furth her conflict. An entirre political generatio on had h been inoculated against ad dventurism m, and the emphasis was on reetrenchmen nt, recoverry and a repara ations. What, if anything, did WW1 resolve? This is a good question in a year where we mark not only the centenary of its outbreak, but also the 70th anniversary of the D-Day landings, which were a pivotal point in the Second World War. Taking the longer view, and a wider perspective, some commentators see the two world wars as inseparable, both being part of the Long War that began in 1914 and ended in 1945, the year that marked a settlement in global politics that raised the USA and the Soviet Union to the rank of global superpower and ended the ambitions of Great Britain, Germany and France to that status. From this perspective, the period 1918-1939 was one of unresolved ambition and manoeuvring in preparation for Round 2. All the more reason, then, to look at the leadership responsible for initiating these worldchanging events. When one looks at the quality of decision making that took place in the years, months and weeks before August 1914 one is struck by a number of features: • The relative homogeneity of the decision making group right the way across Europe, • The lack of self-awareness that led personal neurosis and ambition to be a major factor in decisions, • The relative importance of domestic affairs rather than international relations in many of the decision makers’ minds, • The diffuse nature of power and decision making in each of the major powers, • The widespread fatalism that accepted war as inevitable, and • The presence of leaders who actively sought war, despite • A general lack of appreciation of the implications of recent developments in military technology and organisation and the difference these would make to the experience of warfare. Homegeneity The group that led Europe to war were exclusively white middle-aged or elderly men, all members’ of their national elites: Asquith in London, Poincare in Paris, BethmannHollweg in Germany, Berchtold in Austria-Hungary and Goremykin in Russia. Those who partnered them – the Foreign Ministers and War Ministers and senior civil servants, tended to come from the same mould. They tended to be well-educated, cultured, sophisticated but narrow-minded and limited in experience, and in many ways they had more in common with each other than with broad swathes of their own people. They paid lip service to the myth of The Good King, but none of them actually behaved as if they believed that monarchs were somehow endowed with supernatural powers of wisdom. On the contrary, the interventions of Kaiser Wilhelm in Germany and Tsar Nicholas in Russia were at times profoundly frustrating and destabilising for their political servants. Leadership Lesson: Diversity is important. It ensures a broad range of perspectives and thinking processes. Lack of it can lead to an impoverished decision making process and group-think, which although it feels self-affirming and comfortable can be highly dangerous. Diversity should be welcomed as the source of helpful new perspectives rather than seen as a burden or obligation. 2 Lack of Self Awareness There were occasions when the leaders’ own personal idiosyncrasies got in the way of resolving the growing crisis. Sometimes these were almost comic, if it were not for the tragedy that was unfolding. One example is the painfully shy Count Berchtold’s inability to deal with the Serbian Prime Minister Pasic’s evasive loquaciousness and deliberate obtuseness during a meeting in Vienna, when Austria was attempting to press upon Serbia the seriousness of the situation in the year before the war. Realising his mistake, Berchtold hurriedly wrote a long letter to Pasic in German just as Pasic was leaving Vienna – unfortunately Pasic couldn’t read German and in any case the letter arrived too late, and Berchtold had neglected to retain a copy so Pasic denied ever having seen it. Back in Belgrade, when the letter was eventually translated, the language was apparently too indirect and courteous for the real message to be understood. One has the picture of reserved men with little understanding of why they are there, walking along a path at night, bumping into each other in the dark as they head towards a cliff. Leadership Lesson: Leadership creates huge personal pressures which can profoundly affect how leaders respond. Leadership arenas are complex and shifting and require more personal insight and personal resources than we are aware of in order to deal with them, and so developing personal awareness is a commitment any leader must make in order to both survive and thrive. Developing techniques such as mindfulness practices and courageous conversations can help manage anxiety, improve communication and help us think more clearly under pressure. Parochial Focus When we contemplate the enormity of what happened, it is difficult to appreciate that for many of the players at the time, domestic considerations were as important as international relations, and indeed, heavily influenced the decisions that were being made. In Great Britain, for example, one of the Cabinet’s overriding concerns was the attitude of the British Army towards government policy in Ireland, where protestant unionist activists were threatening an armed insurrection against Home Rule. In the Curragh Incident in January 1914 officers had resigned their commissions rather than take action against the unionists. For the British Government, one of the factors influencing some ministers was the prospect of uniting the Army behind an overseas war, to use Shakespeare’s words ‘busy giddy minds with foreign quarrels’. Every nation in 1914 faced dilemmas caused by conflicting agendas and values. Leadership Lesson: It is sometimes easy, looking back, to assume in hindsight that issues were seen as clearly at the time to those making the decisions as they are to us today. But leaders seldom have single responsibilities; they must weigh the pro’s and con’s across a range of briefs. The difficulties arise when the weightings are layered with emotional attachments, because this is what tends to produce genuine dilemmas – where we are faced with mutually unpleasant outcomes. Transcending dilemmas requires great imagination and a willingness to let go of things to which we are emotionally attached. 3 Diffusion of Power Again, looking back, it is easy to see the decision making process as a rational series of actions taken by individuals with the authority or motivation to act. In fact, it is convenient for us to be able to ascribe meanings to individuals. And yet when one examines the detail, the decision making process of each of the Great Powers was more like a complex interplay of power bases and relationships than the rational outcome of a governing mind. In Britain, for example, there was a powerful civil service clique in the Foreign Office that saw Germany as the main threat, and actively encouraged Britain’s allies to confront Germany. The Foreign Minister, Grey, had made commitments to France that he was largely unwilling to share in public with his ministerial colleagues who were sensitive to any hint of imperial war-mongering. In Russia, the situation was much more complex, with a weak Prime Minister Goremykin being pulled this way and that by a bevy of powerful, theoretically subordinate, ministers. In Austria-Hungary there were in fact two administrations – one for each monarchy – each with rather different interests and attitudes towards the problem of dealing with Slavic minorities in the empire which so aggravated the Serbs. In Serbia itself the Black Hand organisation that initiated the assassination was in effect a secret arm of the militant nationalist wing of Serbian politics, around which Pasic and his government were obliged to tread carefully for fear of assassination themselves. Leadership Lesson: Leaders need to avoid oversimplifying the decision making process when anticipating moves made by the competition. A proper understanding of all the stakeholders involved is essential if dangerous assumptions are to be avoided. Fatalism and War-fever For some of the leaders involved in 1914, war appeared to be inevitable. For the French, the recovery of national honour after the humiliation of defeat by Germany in 1870 was paramount. It influenced French military strategy, which until reality intervened in 1915 was essentially offensive, and ill-equipped to cope with the static warfare that emerged as the trench lines settled across the landscape. It also profoundly influenced French political thinking and foreign policy – the French Prime Minister Poincare appeared set on confrontation. In this context, alliances were actually destabilising factors as they encouraged this kind of thinking rather than ameliorated it. There were those in Russia and Germany who shared Poincare’s enthusiasm. To them, competition between the major powers was a zero sum game in which one could only be either a winner or a loser. Germany was deeply concerned that Russian industrialisation would mean the creation of a military machine that would be irresistible, and that war needed to happen before this occurred. In a sense, they were right: at the end of the Long War in 1945, Russian military might had crushed Germany. Leadership Lesson: Zero sum economics or politics is based on winner-takesall ‘single round gaming’. In life, and business, however, people and organisations need to continue dealing with each other over a long period of time. Collaboration and dialogue become much more important when today’s 4 opposition may become tomorrow’s ally. In the heat of the moment it is easy to forget this, but a simple look at the world in the seventy years since the end of the Long War shows how impermanent alliances can be, and how sustainable relationships cannot stay fixed and need to adapt over time. As the saying goes ‘We thought it was impossible, until we did it.’ Wilful Ignorance Anyone with intelligence who observed the American Civil War a full fifty years before the outbreak of World War 1 would have seen the way modern warfare was heading: the degeneration of mobile warfare into static trench warfare, the impact of mass mobilisation to create huge citizen armies, the innovations of communications (telegraph) and transport (railways). In purely military terms there was the development of air observation balloons, ironclad steam-powered warships, submarines and steel rifled gun barrels to increase the range, speed and accuracy of weapons. Although some of the technological innovations emerged during the First World War – chemical warfare, tanks and aircraft for example, - there were plenty of signs that the kind of war that military leaders planned for and politicians hoped for would not materialise. Britain found herself, for example, completely unprepared for large-scale land warfare in 1914, having a strategy that relied on dispersed small-scale deployments backed by a huge navy in order to protect the trade routes of the Empire. Overnight that strategy was turned upon its head, so it is hardly surprising it took some time to come up with a satisfactory response. The problem was that the new reality did not fit political aspirations, and to a degree the politicians chose to ignore it, while the generals got on with their duty. It is interesting to note that among the victorious politicians after 1918 there was considerable criticism of the generals (Lloyd George was especially scathing of the British High Command), while in Germany and Russia it was the politicians who were accused of betraying the military. Some of the leaders who eventually resolved the conflict in 1945 had learned important lessons – among the British, Churchill and Montgomery; among the Americans, Truman, MacArthur and Patton; among the Germans, Rommel and Kesselring: all had seen service on the battlefield in 1914-18 and would use that learning creatively and successfully in 1939-45. Leadership Lesson: Transitions between stages of development, whether personal, organisational or national, are confusing, difficult and dangerous times. Old trusted methods suddenly stop working, and nobody can be sure what the new model will look like or how it will operate. In these circumstances risks have to be taken, because the risk of staying the same is even greater. Balancing past and present, knowing what to discard and what to keep, is a complex and challenging task, requiring exploration and experimentation. Leaders who never make mistakes, never learn. Final thoughts The tragedy of the First World War is that many of these lessons were not learned, and it took another six years of blood-letting before a new international order could emerge. The outbreak of war in 1914 was by no means inevitable, however hard some worked for it. At any point one or more leaders could have taken a different path, and this could have 5 influenced the rest. That none chose to do so represents a collective failure of imagination, and knowing how to cultivate and encourage the imagination is an essential ingredient of successful leadership. What matters for leaders is not the answers leaders have inside their heads, but the questions they are able and willing to ask. JON CHAPMAN MA MBA, Visiting Fellow, The Praxis Centre Jon worked in industrial market research for several years then moved to the Hay Group as a business analyst and as a management consultant. He spent 15 years in the speciality chemicals industry as Commercial Director and Chief Executive of an independent mediumsized UK company. He was a Council Member and Director of Responsible Care at the UK Chemical Industries Association, involving consultation, lobbying and dialogue with industry, government, regulators, NGO’s and professional bodies at UK, European and international levels. Jon now works full time as a freelance management development consultant and executive coach. Jon’s first degree was in history, for which he won a scholarship to Cambridge University, and in which he retains a strong interest. He has a Cranfield MBA and has undertaken extensive training in personal development techniques. He is a Certified Pesso Boyden therapist. Jon has worked with organisations in both the public and private sector, in the UK and abroad; sectors include mining, automotive, consumer products, utilities, financial services, construction engineering, information systems, healthcare, education, publishing and media, and professional sport. June 2014 6