Interim Evaluation Report: Congressionally Mandated Evaluation of

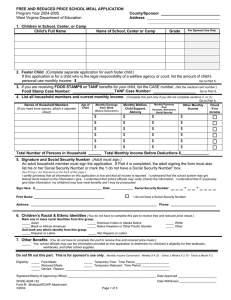

advertisement