THE IMPACT OF SOCIAL SECURITY REFORM ON LOW-INCOME AND OLDER WOMEN

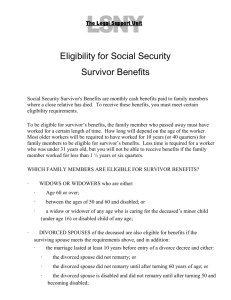

advertisement