TESTING PUBLIC HOUSING DEREGULATION: A SUMMARY ASSESSMENT OF

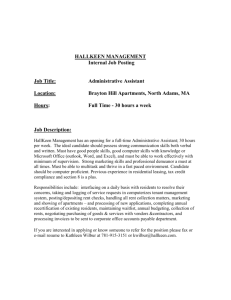

advertisement