The Validity of Interpersonal Skills Assessment Via Situational Judgment

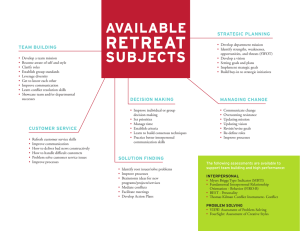

advertisement

Journal of Applied Psychology 2012, Vol. 97, No. 2, 460 – 468 © 2011 American Psychological Association 0021-9010/12/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0025741 RESEARCH REPORT The Validity of Interpersonal Skills Assessment Via Situational Judgment Tests for Predicting Academic Success and Job Performance Filip Lievens Paul R. Sackett Ghent University University of Minnesota, Twin Cities Campus This study provides conceptual and empirical arguments why an assessment of applicants’ procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior via a video-based situational judgment test might be valid for academic and postacademic success criteria. Four cohorts of medical students (N ⫽ 723) were followed from admission to employment. Procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior at the time of admission was valid for both internship performance (7 years later) and job performance (9 years later) and showed incremental validity over cognitive factors. Mediation analyses supported the conceptual link between procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior, translating that knowledge into actual interpersonal behavior in internships, and showing that behavior on the job. Implications for theory and practice are discussed. Keywords: interpersonal skills, situational judgment test, high-stakes testing, student selection, medical selection Situational judgment tests (SJTs) are a step removed from direct observation, and are better viewed as measures of procedural knowledge in a specific domain (e.g., interpersonal skills). SJTs confront applicants with written or video-based scenarios and ask them to indicate how they would react by choosing an alternative from a list of responses (Christian, Edwards, & Bradley, 2010; McDaniel, Hartman, Whetzel, & Grubb, 2007). Widely used in employment contexts, there is also growing interest in the potential use of SJTs in student admission/selection settings (Lievens, Buyse, & Sackett, 2005a; Oswald, Schmitt, Kim, Ramsay, & Gillespie, 2004; Schmitt et al., 2009). The initial evidence for the use of SJTs in such high-stakes settings is promising. In particular, Lievens et al. (2005a) found that a video-based SJT predicted grade point average (GPA) in interpersonal skills courses. Although the results of these studies are promising, they do not address the key issue as to whether students’ interpersonal skills scores on a video-based SJT at the time of admission really achieve long-term prediction of performance in actual interpersonal situations. Such interpersonal interactions can be observed in some academic settings (e.g., in internships) and subsequently on the job after completion of a program of study. Therefore, we use a predictive validation design to examine whether an assessment of interpersonal skills via the use of SJTs at the time of admission predicts academic (internship performance) and postacademic (job performance) criteria. Our study is situated in the context of selection to medical school in Belgium. Medical admissions are a relevant setting for examining the value of interpersonal skills assessments for predicting academic and postacademic success because in many countries, calls have been made to include a wider range of skills in medical admission (Barr, 2010; Bore, Munro, & Powis, 2009; Powis, 2010). Our interest in predicting outcomes other than academic performance, particularly outcomes after students have completed their Terms such as “personal characteristics,” “soft skills,” “noncognitive skills,” and “21st-century skills” are often used to refer to a wide array of attributes (e.g., resilience, honesty, teamwork skills) viewed as valuable in many settings, including work and higher education. There exists a long interest in measuring these noncognitive predictors for use in selection or admission as they enable to go beyond cognitive ability, predict various success criteria, and reduce adverse impact (Kuncel & Hezlett, 2007; Schmitt et al., 2009; Sedlacek, 2004). We focus in this article on one characteristic of broad interest, namely, interpersonal skills. This refers to skills related to social sensitivity, relationship building, working with others, listening, and communication (Huffcutt, Conway, Roth, & Stone, 2001; Klein, DeRouin, & Salas, 2006; Roth, Bobko, McFarland, & Buster, 2008). Over the years, a variety of approaches for measuring interpersonal skills have been proposed and examined. In workplace settings, methods that involve direct observation of interpersonal behavior are widely used (e.g., interviews, work samples, and assessment center exercises; Arthur, Day, McNelly, & Edens, 2003; Ferris et al., 2007; Huffcutt et al., 2001; Roth et al., 2008). In higher education admissions settings, such direct approaches are uncommon, as it is difficult to reliably and formally apply them in the large-scale and high-stakes nature of student admission contexts (Schmitt et al., 2009). This article was published Online First October 3, 2011. Filip Lievens, Department of Personnel Management and Work and Organizational Psychology, Ghent University, Belgium; Paul R. Sackett, Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities Campus. We thank Tine Buyse for her help in collecting the data. Correspondence concering this article should be addressed to Filip Lievens, Department of Personnel Management and Work and Organizational Psychology, Ghent University, Henri Dunantlaan 2, 9000 Ghent, Belgium. E-mail: filip.lievens@ugent.be 460 INTERPERSONAL SKILLS AND SITUATIONAL JUDGMENT TESTS studies and entered their chosen profession, fits in a growing trend in graduate and professional education (Kuncel & Hezlett, 2007; Kuncel, Hezlett, & Ones, 2004; Schultz & Zedeck, 2008). This trend has also generated some discussion. Specifically, two differing perspectives on the appropriate role of tests used in the admission process can be distinguished. One perspective posits that predicting academic outcomes (e.g., GPA) is an insufficient basis for the justification of the use of admission tests, as academic outcomes are not of interest in and of themselves. From this perspective, links to postacademic (employment) performance are essential for justifying test use. A competing perspective is that the goal of admission testing is to identify students who will develop the highest level of knowledge and skill in the curriculum of interest, as such knowledge and skill is the foundation for effective practice in a profession. From this perspective, research linking admissions tests to postacademic outcomes is not critical to the justification of test use. This debate on the appropriate role of admissions tests reflects value judgments, and thus cannot be resolved by research. Nonetheless, regardless of whether links to postacademic outcomes are or are not viewed as critical to justifying test use, we believe that an investigation of these linkages helps to better understand what tests can and cannot accomplish. By linking a test given as part of an admission process with job performance subsequent to degree completion, this study also spans the education and employment worlds. Interpersonal Skills and SJTs Recent taxonomies of interpersonal skills (Carpenter & Wisecarver, 2004; Klein et al., 2006) make a distinction between two metadimensions, namely, building and maintaining relationships (e.g., helping and supporting others) and communication/ exchanging information (e.g., informing and gathering information). In the medical field, the “building and maintaining relationships” and “communication/exchanging information” have also been proposed as key dimensions for effective physician–patient interactions (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, 2010; Makoul, 2001). For example, the clinical skills examination checklist used by the National Board of Medical Examiners includes items such as listening carefully to patients or encouraging patients to express thoughts and concerns (indicators of building and maintaining relationships) and using words that patients can understand or using clear and precise speech (indicators of communication/exchanging information). In this study, students’ interpersonal skills in the physician– patient interaction were assessed via a video-based SJT. A higher fidelity video-based format is particularly relevant in this context as meta-analytic evidence has revealed a large validity difference between video-based and written SJTs (.47 vs. .27) for measuring interpersonal skills (Christian et al., 2010). The SJT contained video-based situations related to the dimensions of “building and maintaining relationships” and “communication/exchanging information,” which is consistent with the emphasis placed on those dimensions by interpersonal skills taxonomies and medical examination boards. For example, the SJT included situations dealing with showing consideration and interest, listening to patients, conveying bad news, reacting to patients’ refusal to take the prescribed medicine, or using appropriate language for explaining 461 technical terms. No medical knowledge was necessary to complete the SJT. The assumption underlying the use of an SJT in a medical admission context was that students’ scores on such interpersonally oriented SJT situations at the time of admission will predict their performance in future actual interactions with patients, as observed/rated during internships and many years later on the job. So, even though students at the time of admission might not have any experience as physicians with patient situations, we expect their answers on the video-based SJT situations to be predictive of their future internship and job performance. Conceptually, this expectation is based on the theory of knowledge determinants underlying SJT performance (Motowidlo & Beier, 2010; Motowidlo, Hooper, & Jackson, 2006). According to Motowidlo et al., an SJT is a measure of procedural knowledge, which can be broken down in job-specific procedural knowledge and general/nonjobspecific procedural knowledge. Whereas the former type of knowledge is based on job-specific experience, the latter accrues from experience in general situations. As SJTs used in admission exams do not rely on job-specific knowledge, only general procedural knowledge is relevant. Motowidlo defined this general procedural knowledge as the knowledge somebody has acquired about effective and ineffective courses of trait-related behavior in situations like those described in the SJT. Applied to this study’s interpersonally oriented SJT, this general procedural knowledge relates to students’ procedural knowledge about (in)effective behavior in interpersonal situations (with patients) as depicted in the SJT items. This procedural knowledge about costs and benefits of engaging in interpersonally oriented behavior is considered to be a precursor of actual behavior in future interpersonal situations (Lievens & Patterson, 2011; Motowidlo & Beier, 2010; Motowidlo et al., 2006). So, the assumption is that students with substantial procedural knowledge about effective behavior in interpersonal situations as assessed by an SJT will also show superior interpersonal performance when they later interact with actual patients as compared with students with inadequate procedural knowledge about effective interpersonal behavior. Stability of Interpersonal Skills When considering the use of measures of procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior to predict both academic and postacademic employment criteria that span multiple years, it is important to consider the stability of the interpersonal skills construct. Hypothesizing such relationships requires the assumption of some degree of stability in students’ interpersonal knowledge and skills as they progress through the curriculum and onto the job. In the vast literature on dynamic criteria (Alvares & Hulin, 1972; Barrett, Phillips, & Alexander, 1981; Campbell & Knapp, 2001; Deadrick & Madigan, 1990; Ghiselli, 1956; Schmidt, Hunter, Outerbridge, & Goff, 1988), this issue as to whether individuals change over time is captured by the “changing person” model. In the ability domain, the changing person explanation has now been largely rejected as postdictive validities appear to follow the same patterns of changes as predictive validities (Humphreys & Taber, 1973; Lunneborg & Lunneborg, 1970). Similar arguments of stability have been made for personality traits, as meta-analytic evidence (Fraley & Roberts, 2005; Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000) suggests that rank-order stability is high (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005). LIEVENS AND SACKETT 462 At first glance, one might expect a different pattern of findings in the interpersonal skills domain, as training programs and courses aim to change these skills, and are successful at doing so. Arthur, Bennett, Edens, and Bell’s (2003) meta-analysis of training program effectiveness reports mean ds for interpersonal skills of 0.68 for learning criteria and 0.54 for behavioral criteria. However, in considering the implications of this for the changing person model, it is important to consider the implications of different types of change. Here we consider four possible ways for interpersonal skills to be changed by intervention. First, an intervention might improve the skills of all individuals by a comparable amount, in which case the validity of a predictor of interpersonal skills would be unaffected. Second, an intervention might improve the skills of those with severe deficits, but have little impact on those with good skills. In this case, it is possible that rank order is unchanged; all that is seen is a tightening of the distribution, and the validity of an interpersonal skills predictor is also affected only to a limited degree. Third, the intervention might train all individuals to a common level of interpersonal skill, in which variance would be reduced to zero, and therefore validity of a predictor would also go to zero. Fourth, the intervention might be differentially effective, resulting in substantial change in the rank ordering of individuals in terms of their interpersonal skills, and thus in substantial reduction in validity. For example, Ceci and Papierno (2005) report that it is not uncommon for those with higher preintervention scores to benefit more from the intervention than those with lower scores. Thus, the first two possible forms of “changing abilities” pose no threat to validity, whereas the last two forms do pose a threat. However, we note that if either of these latter two forms were the true state of affairs, one would observe very low pretest–posttest correlations between measures of interpersonal skills. In contrast, a high pretest–posttest correlation would be strong evidence against these latter two forms. We find such evidence in a metaanalysis by Taylor, Russ-Eft, and Chan (2005) of behavioral modeling training programs aimed at interpersonal skills. They reported a mean pretest–posttest correlation of .84 across 21 studies for the effects of training on job behaviors, which is inconsistent with either the “training eliminates variance” or the “training radically alters rank order” perspectives. Thus, we expect that the forms of a “changing persons” argument that would lead to reduced validity can also be rejected in the interpersonal skills domain. model. One might consider performance on an interpersonally oriented SJT, internship performance with patients, and job performance with actual patients as assessments of interpersonal skills that differ in their degree of fidelity. Hereby fidelity refers to the extent to which the assessment task and context mirror those actually present on the job (Callinan & Robertson, 2000; Goldstein, Zedeck, & Schneider, 1993). As noted above, an interpersonal SJT serves as an interpersonal skills assessment with a low degree of fidelity because it assesses people’s procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior instead of their actual behavior. Next, internship performance can be considered a high-fidelity assessment (Zhao & Liden, 2011) because during internships, individuals have the opportunity to interact with real patients under close supervision. However, they work only with a small number of patients and have no responsibility for those patients. Finally, physicians’ demonstration of interpersonal skills with actual patients on the job is no longer a simulation as it constitutes the criterion to be predicted. All of this suggests a mediated model wherein procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior (lowfidelity assessment) predicts internship performance (high-fidelity assessment), which in turn predicts job performance (criterion). So far, no studies have scrutinized these causal links between lowfidelity/high-fidelity samples and the criterion domain. We posit the following: Hypothesis 2 (H2): The relationship between procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior (low-fidelity assessment) and job performance (criterion) will be mediated by internship performance (high-fidelity assessment). It should be noted that internship and job performance are multidimensional because in this study, performance on both involves a combination of interpersonal as well as technical knowledge/skills. So, internship and job performance are saturated with both interpersonal and technical/medical skills. Saturation refers to how a given construct (e.g., interpersonal skills) influences a complex multidimensional measure (e.g., ratings of job performance; Lubinski & Dawis, 1992; Roth et al., 2008). The multidimensional nature of internship and job performance makes it useful to examine the incremental contribution of procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior over and above other factors (i.e., cognitive factors) influencing performance. In particular, we expect the SJT to offer incremental validity over cognitive factors in predicting internship and job performance. Thus, On the basis of the above discussion, we posit the following hypotheses: Hypothesis 3a (H3a): Procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior (assessed by an SJT) will have incremental validity over cognitive factors for predicting internship performance. Hypothesis 1a (H1a): Procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior (assessed by an SJT at the time of admission) will be a valid predictor of internship performance. Hypothesis 3b (H3b): Procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior (assessed by an SJT) will have incremental validity over cognitive factors for predicting job performance. Hypotheses Hypothesis 1b (H1b): Procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior (assessed by an SJT at the time of admission) will be a valid predictor of job performance. Using the behavioral consistency logic (Schmitt & Ostroff, 1986), these first hypotheses might be tested together in a mediated Method Sample and Procedure This study’s sample consisted of 723 students (39% men and 61% women; average age ⫽ 18 years and 4 months; 99.5% INTERPERSONAL SKILLS AND SITUATIONAL JUDGMENT TESTS Caucasian) who completed the Medical Studies Admission Exam in Belgium, passed the exam, and undertook medical studies. This sample includes four entering cohorts of students who had completed the exam between 1999 and 2002. We focused on these four cohorts because criterion data for the full curriculum (7 years) were available from them. On average, the passing rate of the admission exam was about 30%. Candidates who passed the exam received a certificate that warranted entry in any medical university. Thus, there was no further selection on the part of the universities. This sample came from a population of 5,444 students (63% women, 37% men; average age ⫽ 18 years and 10 months; 99.5% Caucasian) who completed the examination between 1999 and 2002. Data on this total applicant pool will be used for range restriction corrections to estimate validity in the applicant pool (see below). Predictor Measures Students’ scores on the predictor measures were gathered during the actual admission exam. Each year, the exam lasted for a whole day and was centrally administered in a large hall. To preserve the integrity of the tests, alternate forms per test were developed each year. Therefore, candidates’ test scores were standardized within each exam. Cognitive composite. In their meta-analysis, Kuncel, Hezlett, and Ones (2001) showed that a composite of general measures (e.g., Graduate Record Exam [GRE] verbal and numerical) combined with specific GRE subject-matter tests provided the highest validity in predicting academic performance. To provide the strongest test of the incremental validity of interpersonal skills, a cognitive composite was used that consisted of four science knowledge test scores (biology, chemistry, mathematics, and psychics) and a general mental ability test score. The science-related subjects consisted of 40 questions (10 questions per subject) with four alternatives. The general mental ability test consisted of 50 items with five possible answers. The items were formulated in verbal, numeric, or figural terms. In light of test security, we cannot mention the source of this test. Prior research demonstrated the satisfactory reliability and validity of this cognitive composite for a medical student population (Lievens et al., 2005a). Medical text. In this test, candidate medical students were asked to read and understand a text with a medical subject matter. Hence, this test can be considered a miniaturized sample of tasks that students will encounter in their education. The texts developed typically drew on texts from popular medical journals. Students had 50 min to read the text and answer 30 multiple-choice questions (each with four possible answers). Across the exams, the average internal consistency coefficient of this test equaled .71. Video-based SJT. The general aim of the video-based SJT was to measure interpersonal skills. As noted above, the videobased SJT focused on the “building and maintaining relationships” and “communication/exchanging information” components of interpersonal skills. First, realistic critical incidents regarding these domains were collected from experienced physicians and professors in general medicine. Second, vignettes that nested these incidents were written. Two professors teaching physicians’ consulting practices tested these vignettes for realism. Using a similar approach, questions and response options were derived. Third, 463 semiprofessional actors were hired and videotaped. Finally, a panel of experienced physicians and professors in general medicine developed a scoring key. Agreement among the experts was satisfactory, and discrepancies were resolved upon discussion. The scoring key indicated what response alternative was correct for each item (⫹1 point). In its final version, the SJT consisted of videotaped vignettes of interpersonal situations that physicians are likely to encounter with patients. After each critical incident, the scene froze, and candidates received 25 s to answer the question (“What is the most effective response?”). In total, the SJT consisted of 30 multiple-choice questions with four possible answers. Prior research attests to the construct-related validity of the SJTs developed as they consistently correlated with scores on interpersonally oriented courses in the curriculum (Lievens et al., 2005a). Prior studies also revealed that alternate form reliability of the SJTs was .66 (Lievens, Buyse, & Sackett, 2005b), which was consistent with values obtained in studies on alternate form SJTs (Clause, Mullins, Nee, Pulakos, & Schmitt, 1998). Operational composite. To make actual admission decisions, a weighted sum of the aforementioned predictors (cognitively oriented tests, medical text, and SJT) was computed. The weights and cutoff scores were determined by law, with the most weight given to the cognitive composite. A minimal cutoff was determined on this operational composite. Criterion Measures Internship performance rating. Two of the authors inspected the descriptions of the medical curricula of the universities. To qualify as an “internship,” students had to work in a temporary position with an emphasis on on-the-job training and contact with patients (instead of with simulated patients). Interrater reliability (ICC 2,1) among the authors was ⬎ .90. In four of the seven academic years (first, fourth, sixth, and seventh year), internships were identified. Whereas in the first year the internship had a focus on observation, the other internships were clinical clerkships lasting 2– 4 months in different units. In their internships, students were evaluated on their technical (e.g., examination skills) and interpersonal skills (e.g., contact with patients) using detailed score sheets. Internship ratings of 606 students were obtained from archival records of the universities. Only the global internship ratings were available. Those ratings ranged from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating better ratings. Given differences across universities, students’ internship ratings were standardized within university and academic year. As the four internship ratings were significantly correlated, a composite internship performance rating was computed. Job performance rating. Some of the medical students of this study (about 20%, n ⫽ 103) who ended their 7 years of education chose a career in general medicine and entered a General Practitioner training program of up to 2 years duration. During that program, they worked under the supervision of a registered General Practitioner in a number of general practice placements. At the end of the training program, all trainees were rated on a scale from 0 to 20 by their supervisor. None of the supervisors had access to the trainees’ admissions scores. Similar evaluation sheets (with a focus on technical and interpersonal skills) were used for internship performance ratings. Only the global job performance ratings LIEVENS AND SACKETT 464 were available from the archives. As expected, internship and job performance were moderately correlated (corrected r ⫽ .40). As the above description refers to participants as “trainees,” a question arises as to whether this should be viewed as a measure of “training performance” rather than of “job performance.” We view this as “job performance” in that these graduates are engaged in full-time practice of medicine. They are responsible for patients while they work under supervision of a General Practitioner charged with monitoring and evaluating their work. GPA. Although no hypotheses were developed for students’ GPA, this criterion (average GPA across 7 years) was included by way of a comparison with prior studies. Given differences across universities, students’ GPA was standardized within university and academic year prior to making a composite. Range Restriction In this study, students were selected on an operational composite of the various predictors, leading to indirect range restriction on each individual predictor. Given that indirect range restriction is a special case of multivariate range restriction, the multivariate range restriction formulas of Ree, Carretta, Earles, and Albert (1994) were applied to the uncorrected correlation matrix. As recommended by Sackett and Yang (2000), statistical significance was determined prior to correcting the correlations. Results Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations among the predictors. In Table 2, the correlations between the predictors and the criteria are shown. The values below the diagonal of Table 2 represent the corrected correlations between the predictors and performance. The values above the diagonal are the uncorrected correlations. Consistent with prior research, the corrected correlation between the cognitive composite and overall academic performance (GPA after 7 years) equaled .36. This was significantly higher than the corrected correlation (.15) between the SJT and GPA, t(720) ⫽ 4.31, p ⬍ .001. Our first hypotheses dealt with the validity of procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior for predicting internship (H1a) and job performance (H1b). Table 2 shows that the corrected validities of the interpersonal SJT for predicting overall internship performance and supervisory-rated job performance were .22 and .21. These results support H1a and H1b. Although the corrected correlations of the SJT with both criteria were higher than the corrected validities of the cognitive composite (.13 and .10, respectively), it should be noted that these differences were not statistically significant. H2 posited that a high-fidelity assessment of interpersonal behavior would mediate the relationship between a low-fidelity assessment of that behavior and job performance. All requirements for mediation according to Baron and Kenny (1986) were met (see Table 3). The effect of the interpersonal SJT on job performance dropped from .26 to .10 when the mediator (internship performance) was controlled for. To statistically test the mediating role of internship performance, we used the bootstrapping method (Preacher & Hayes, 2004; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). This was done on the uncorrected correlation matrix because it was not possible to run a bootstrapping procedure on a corrected matrix. Bootstrapping procedures showed a point estimate of .16 for the indirect effect of the interpersonal SJT on job performance through internship performance (95% CI [.04, .29]). Thus, H2 was supported. The third hypotheses related to the incremental validity of procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior (as measured via an SJT) over cognitive factors for predicting internship and job performance. We conducted hierarchical regression analyses, with the matrices corrected for multivariate range restriction serving as input. The cognitive composite was entered as a first block because such tests have been traditionally used in admissions. As a second block, the medical text was entered. Finally, we entered the SJT. Table 4 shows the SJT explained incremental variance in internship (5%) and job performance (5%), supporting H3a and H3b. It should be noted, though, that these results were obtained with the other two predictors not being significant predictors of the criteria. Discussion This study focused on the assessment of interpersonal skills via SJTs. Key results were that procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior as measured with an SJT at the time of admission was valid for both internship (7 years later) and job performance (9 years later). Moreover, students’ procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior showed incremental validity over cognitive factors for predicting these academic and postacademic success criteria, underscoring the role of SJTs as “alternative” predictors in Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Predictors in the Sample Selectees (n ⫽ 723) Applicant population (N ⫽ 5,439) Variable 1. 2. 3. 4. Cognitive composite Written text SJT Operational composite M SD 1 2 11.68 15.17 18.35 20.66 2.65 4.74 3.08 5.29 — .36 .20 .91 — .24 .45 General practitioners (n ⫽ 103) 3 M SD M SD — .28 14.08 16.81 19.30 24.90 1.67 4.47 2.84 3.89 13.60 16.30 20.15 24.63 1.47 4.16 2.66 4.04 Note. Although all analyses were conducted on standardized scores, this table presents the raw scores across exams. The maximum score on each test was 30, with the exception of the operational composite (maximum score ⫽ 40). Both the selectees (i.e., medical students) and general practitioners are subsamples of the applicant sample. Correlations between the predictors in the applicant group are presented. All correlations are significant at p ⬍ .01. SJT ⫽ situational judgment test. INTERPERSONAL SKILLS AND SITUATIONAL JUDGMENT TESTS 465 Table 2 Correlations Among Predictors and Criteria in Selected Sample Variable Predictors (N ⫽ 723) 1. Cognitive composite 2. Written text 3. SJT 4. Operational composite Criteria 5. GPA (N ⫽ 713) 6. Internship performance (N ⫽ 606) 7. Job performance (N ⫽ 103) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 — .13 .03 .86 ⫺.01 — .15 .28 ⫺.06 .13 — .16 .75 .19 .11 — .27 .05 .10 .23 .09 .01 .21 .09 .13 ⫺.12 .21 .00 .36 .13 .10 .10 .03 ⫺.12 .13 .22 .21 .34 .14 .01 — .61 .37 .60 — .40 .38 .40 — Note. Correlations were corrected for multivariate range restriction. Uncorrected correlations are above the diagonal, corrected correlations are below the diagonal. Apart from the last row, correlations higher than .09 are significant at the .05 level; correlations higher than .12 are significant at the .01 level. For the last row, correlations higher than .20 are significant at the .05 level; correlations higher than .26 are significant at the .01 level. SJT ⫽ situational judgment test; GPA ⫽ grade point average. analyses confirmed that the link between a low-fidelity assessment of criterion behavior (i.e., procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior via an SJT) and criterion ratings (job performance) was mediated by a high-fidelity (internship) assessment of criterion behavior. So, as a key theoretical contribution, we found support for a conceptual link between possessing procedural knowledge about interpersonal behavior, translating that knowledge into actual interpersonal behavior in constrained settings such as internships, and showing that interpersonal behavior later on the job. This study is also the first to establish evidence of the long-term predictive power of an interpersonal skills assessment via SJTs. That is, an operational SJT administered at the time of application for admission retained its validity many years later as a predictor selection. These findings speak not only to the potential role of interpersonal skills assessment via SJTs in higher education admissions but also to its relevance in the employment world. A contribution of this study was that we tested conceptual arguments why the assessment of interpersonal skills via SJTs is predictive of future academic and postacademic performance. On the basis of the theory of knowledge determinants underlying SJT performance (Motowidlo & Beier, 2010; Motowidlo et al., 2006), we hypothesized that students’ procedural knowledge about costs and benefits of engaging in specific interpersonally oriented behavior that is assessed at the time of admission via an SJT will be a precursor of future actual behavior in interpersonal situations as encountered during internships and on the job. Our mediation Table 3 Regression Results for Mediation Variable Direct and total effects Equation 1 Dependent variable ⫽ Internship performance Independent variable ⫽ Interpersonal SJT Equation 2 Dependent variable ⫽ Job performance Independent variable ⫽ Interpersonal SJT Equation 3 Dependent variable ⫽ Job performance Independent variable ⫽ Internship performance Independent variable ⫽ Interpersonal SJT Indirect effect and significance using normal distribution Sobel Bootstrap results for indirect effect Effect b SE t p .32 .08 3.85 .001ⴱⴱⴱ .26 .12 2.19 .03ⴱ .52 .10 .14 .12 3.80 0.81 .001ⴱⴱⴱ .42 Value SE LL 95% CI UL 95% CI z p 0.17 0.06 .04 .29 2.66 .01 M SE LL 95% CI UL 95% CI 0.16 0.06 .07 .28 Note. N ⫽ 103. Results are based on the uncorrected correlation matrix. Values were rounded. Unstandardized regression coefficients are reported. Bootstrap sample size ⫽ 1,000. SJT ⫽ situational judgment test; LL ⫽ lower limit; UL ⫽ upper limit; CI ⫽ confidence interval. Listwise deletion of missing data. ⴱ p ⬍ .05. ⴱⴱⴱ p ⬍ .01. LIEVENS AND SACKETT 466 Table 4 Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analyses of Predictors on Internship and Job Performance Internship performance (N ⫽ 606) Job performance (N ⫽ 103) Model Predictors  R2 ⌬R2  R2 ⌬R2 1 2 3 Cognitive composite Reading text SJT .13ⴱ ⫺.02 .22ⴱⴱ .02ⴱ .02 .06 .02 .00 .05ⴱⴱ .12 ⫺.17 .23ⴱ .01 .03 .08 .01 .02 .05ⴱ Note. The corrected correlation matrix served as input for the regression analysis. Parameter estimates are for the last step, not entry. Due to rounding, ⌬R2 differs .01 from the cumulative R2. SJT ⫽ situational judgment test. ⴱ p ⬍ .05. ⴱⴱ p ⬍ .01. of academic and postacademic criteria. This finding has theoretical implications as it informs the discussion of whether it is useful to select people on skills that will be taught to them later on. As noted in the introduction, there are a number of possible patterns of change in interpersonal skills over the course of one’s training. Attempts to select on the basis of interpersonal skills would be inappropriate if training eliminated variance (e.g., all were trained to a common level of skill) or resulted in a change in the rank ordering of individuals that was unrelated to initial skill level. Both of these are ruled out by the present findings, namely that predictive relationships still applied for interpersonal criteria that were gathered many years later (i.e., up to 9 years later after SJT administration). This is an important finding as most prior SJT studies were concurrent in nature or relied on predictors gathered after the first 6 months. Moreover, our results demonstrate that selecting on interpersonal skills early on is worthwhile. Training on them later on does not negate the value of selection. The challenge of broadening both criteria and predictors with noncognitive factors runs as a common thread through scientific and societal discussions about selection and admission processes. At a practical level, our results demonstrate that SJTs might be up to this challenge as they provide practitioners with an efficient formal method for measuring procedural knowledge of interpersonal skills early on. Accordingly, this study lends evidence for the inclusion of SJTs in formal school testing systems when decision makers have made a strategic choice of emphasizing an interpersonal skills orientation in their programs. Presently, one commonly attempts to assess (inter)personal attributes through mechanisms such as interviews or letters of recommendation or personal statements, whereas the formal system focuses only on academic achievement in science domains and specific cognitive abilities (Barr, 2010). Hereby it should be clear that measures such as SJTs are not designed to replace traditional cognitive predictors. Instead, they are meant to increase the coverage of skills not measured by traditional predictors. In particular, we see two possibilities for implementing SJTs as measures of procedural interpersonal knowledge in selection practice alongside cognitive skills assessment. One is to use the SJT at the general level of broad admissions exams to college. Another option is to implement the SJT at the level of school-specific additional screening of students who have met prior hurdles in the admission process. However, a caveat that qualifies these practical implications is in order. A contextual feature worthy of note of this study is that to the best of our knowledge, there was no flourishing commercial test coaching industry in Belgium focusing on the SJT at the time of these cohorts (1999 –2002). At that time, coaching mostly focused on the cognitive part of the exam. In more recent years, commercial coaching programs related to the interpersonal component have also arisen, and it will be useful to examine SJT validity under this changed field context. So far, only laboratory studies on SJT coaching (Cullen, Sackett, & Lievens, 2006; Ramsay et al., 2003) have been reported (with results indicative of moderate effect sizes). Several limitations of this study should be mentioned. Like virtually all studies in the selection literature, this study reflects an examination of a single testing program in a single setting. We make no grand claims of generalizability; rather, we believe that it is useful to illustrate that an assessment of interpersonal skills via SJTs can predict performance during internships and in a subsequent work setting. Another limitation is the small sample size (N ⫽ 103) for the analysis of validity against job performance criteria. We also wish N were larger, but note that we are studying the entire population of these medical school graduates moving into general practice. The rarity of studies following individuals from school entry to subsequent job performance 9 years after administration of the predictor measure makes this a useful study to report, in our opinion, despite this limitation. Additional studies using this strategy are certainly needed before strong conclusions can be drawn. In terms of future research, we need more studies that integrate both education and work criteria as they provide a more comprehensive and robust view of the validity of admission/ selection procedures. Such research might provide important evidence to relevant stakeholders (e.g., students, admission systems, schools, organizations, general public) that the selection procedures used are valid for predicting both academic and job performance. In the future, the adverse impact of SJTs in student admissions should also be scrutinized. Along these lines, Schmitt et al. (2009) provided evidence that the demographic composition of students was more diverse when SJTs and biodata measures were used. However, that study was conducted in a research context. Therefore, studies in which the potential adverse impact reduction is examined via the use of noncognitive measures in actual admission and selection contexts are needed. INTERPERSONAL SKILLS AND SITUATIONAL JUDGMENT TESTS References Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. (2010). ACGME general competencies and outcomes assessment for designated institutional officials. Retrieved from http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/irc/ irc_competencies.asp Alvares, K. M., & Hulin, C. L. (1972). Two explanations of temporal changes in ability-skill relationships: A literature review and theoretical analysis. Human Factors, 14, 295–308. Arthur, W., Jr., Bennett, W., Jr., Edens, P. S., & Bell, S. T. (2003). Effectiveness of training in organizations: A meta-analysis of design and evaluation features. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 234 –245. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.234 Arthur, W., Jr., Day, E. A., McNelly, T. L., & Edens, P. S. (2003). A meta-analysis of the criterion-related validity of assessment center dimensions. Personnel Psychology, 56, 125–153. doi:10.1111/j.17446570.2003.tb00146.x Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 Barr, D. A. (2010). Science as superstition: Selecting medical students. The Lancet, 376, 678 – 679. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61325-6 Barrett, G. V., Phillips, J. S., & Alexander, R. A. (1981). Concurrent and predictive validity designs: A critical reanalysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 66, 1– 6. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.66.1.1 Bore, M., Munro, D., & Powis, D. A. (2009). A comprehensive model for the selection of medical students. Medical Teacher, 31, 1066 –1072. doi:10.3109/01421590903095510 Callinan, M., & Robertson, I. T. (2000). Work sample testing. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 8, 248 –260. doi:10.1111/ 1468-2389.00154 Campbell, J. P., & Knapp, D. J. (Eds.). (2001). Exploring the limits in personnel selection and classification. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Carpenter, T. D., & Wisecarver, M. M. (2004). Identifying and validating a model of interpersonal performance dimensions (ARI Technical Report No. 1144). Alexandria, VA: United States Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences. Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W., & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 453– 484. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913 Ceci, S. J., & Papierno, P. B. (2005). The rhetoric and reality of gap closing: When the “have-nots” gain but the “haves” gain even more. American Psychologist, 60, 149 –160. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.2.149 Christian, M. S., Edwards, B. D., & Bradley, J. C. (2010). Situational judgment tests: Construct assessed and a meta-analysis of their criterionrelated validities. Personnel Psychology, 63, 83–117. doi:10.1111/ j.1744-6570.2009.01163.x Clause, C. S., Mullins, M. E., Nee, M. T., Pulakos, E., & Schmitt, N. (1998). Parallel test form development: A procedure for alternative predictors and an example. Personnel Psychology, 51, 193–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1998.tb00722.x Cullen, M. J., Sackett, P. R., & Lievens, F. (2006). Threats to the operational use of situational judgment tests in the college admission process. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 14, 142–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2389.2006.00340.x Deadrick, D. L., & Madigan, R. M. (1990). Dynamic criteria revisited: A longitudinal study of performance stability and predictive validity. Personnel Psychology, 43, 717–744. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1990 .tb00680.x Ferris, G. R., Treadway, D. C., Perrewé, P. L., Brouer, R. L., Douglas, C., & Lux, S. (2007). Political skill in organizations. Journal of Management, 33, 290 –320. doi:10.1177/0149206307300813 Fraley, R., & Roberts, B. W. (2005). Patterns of continuity: A dynamic 467 model for conceptualizing the stability of individual differences in psychological constructs across the life course. Psychological Review, 112, 60 –74. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.112.1.60 Ghiselli, E. E. (1956). Dimensional problems of criteria. Journal of Applied Psychology, 40, 1– 4. doi:10.1037/h0040429 Goldstein, I. L., Zedeck, S., & Schneider, B. (1993). An exploration of the job analysis-content validity process. In N. Schmitt & W. C. Borman (Eds.), Personnel selection in organizations (pp. 2–34). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. Huffcutt, A. I., Conway, J. M., Roth, P. L., & Stone, N. J. (2001). Identification and meta-analytic assessment of psychological constructs measured in employment interviews. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 897–913. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.897 Humphreys, L. G., & Taber, T. (1973). Postdiction study of the Graduate Record Examination and eight semesters of college grades. Journal of Educational Measurement, 10, 179 –184. doi:10.1111/j.17453984.1973.tb00795.x Klein, C., DeRouin, R. E., & Salas, E. (2006). Uncovering workplace interpersonal skills: A review, framework, and research agenda. In G. P. Hodgkinson & J. K. Ford (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 21, pp. 79 –126). New York, NY: Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9780470696378.ch3 Kuncel, N. R., & Hezlett, S. A. (2007, February 23). Standardized tests predict graduate students’ success. Science, 315, 1080 –1081. doi: 10.1126/science.1136618 Kuncel, N. R., Hezlett, S. A., & Ones, D. S. (2001). A comprehensive meta-analysis of the predictive validity of the graduate record examinations: Implications for graduate student selection and performance. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 162–181. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.162 Kuncel, N. R., Hezlett, S. A., & Ones, D. S. (2004). Academic performance, career potential, creativity, and job performance: Can one construct predict them all? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 148 –161. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.148 Lievens, F., Buyse, T., & Sackett, P. R. (2005a). The operational validity of a video-based situational judgment test for medical college admissions: Illustrating the importance of matching predictor and criterion construct domains. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 442– 452. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.3.442 Lievens, F., Buyse, T., & Sackett, P. R. (2005b). Retest effects in operational selection settings: Development and test of a framework. Personnel Psychology, 58, 981–1007. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00713.x Lievens, F., & Patterson, F. (2011). The validity and incremental validity of knowledge tests, low-fidelity simulations, and high-fidelity simulations for predicting job performance in advanced-level high-stakes selection. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 927–940. Lubinski, D., & Dawis, R. V. (1992). Aptitudes, skills, and proficiencies. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 3, 2nd ed., pp. 1–59). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Lunneborg, C. E., & Lunneborg, P. W. (1970). Relations between aptitude changes and academic success during college. Journal of Educational Psychology, 61, 169 –173. doi:10.1037/h0029253 Makoul, G. (2001). Essential elements of communication in medicine encounters: The Kalamazoo Consensus Statement. Academic Medicine, 76, 390 –393. doi:10.1097/00001888-200104000-00021 McDaniel, M. A., Hartman, N. S., Whetzel, D. L., & Grubb, W. L. (2007). Situational judgment tests, response instructions, and validity: A metaanalysis. Personnel Psychology, 60, 63–91. doi:10.1111/j.17446570.2007.00065.x Motowidlo, S. J., & Beier, M. E. (2010). Differentiating specific job knowledge from implicit trait policies in procedural knowledge measured by a situational judgment test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 321–333. doi:10.1037/a0017975 Motowidlo, S. J., Hooper, A. C., & Jackson, H. L. (2006). Implicit policies 468 LIEVENS AND SACKETT about relations between personality traits and behavioral effectiveness in situational judgment items. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 749 – 761. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.749 Oswald, F. L., Schmitt, N., Kim, B. H., Ramsay, L. J., & Gillespie, M. A. (2004). Developing a biodata measure and situational judgment inventory as predictors of college student performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 187–207. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.2.187 Powis, D. (2010). Improving the selection of medical students. British Medical Journal, 340, 708. doi:10.1136/bmj.c708 Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717–731. doi:10.3758/ BF03206553 Ramsay, L. J., Gillespie, M. A., Kim, B. H., Schmitt, N., Oswald, F. L., Drzakowski, S. M., & Friede, A. J. (2003, November). Identifying and preventing score inflation on biodata and situational judgment inventory items. Invited presentation to the College Board, New York, NY. Ree, M. J., Carretta, T. R., Earles, J. A., & Albert, W. (1994). Sign changes when correcting for restriction of range: A note on Pearson’s and Lawley’s selection formulas. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 298 – 301. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.79.2.298 Roberts, B. W., & DelVecchio, W. F. (2000). The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 3–25. doi:10.1037/ 0033-2909.126.1.3 Roth, P., Bobko, P., McFarland, L., & Buster, M. (2008). Work sample tests in personnel selection: A meta-analysis of Black–White differences in overall and exercise scores. Personnel Psychology, 61, 637– 661. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00125.x Sackett, P. R., & Yang, H. (2000). Correction for range restriction: An expanded typology. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 112–118. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.112 Schmidt, F. L., Hunter, J. E., Outerbridge, A. N., & Goff, S. (1988). Joint relation of experience and ability with job performance: Test of three hypotheses. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73, 46 –57. doi:10.1037/ 0021-9010.73.1.46 Schmitt, N., Keeney, J., Oswald, F. L., Pleskac, T., Quinn, A., Sinha, R., & Zorzie, M. (2009). Prediction of 4-year college student performance using cognitive and noncognitive predictors and the impact of demographic status on admitted students. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1479 –1497. doi:10.1037/a0016810 Schmitt, N., & Ostroff, C. (1986). Operationalizing the “behavioral consistency” approach: Selection test development based on a contentoriented strategy. Personnel Psychology, 39, 91–108. doi:10.1111/ j.1744-6570.1986.tb00576.x Schultz, M. M., & Zedeck, S. (2008). Identification, development, and validation of predictors of successful lawyering. Retrieved from http:// www.law.berkeley.edu/files/LSACREPORTfinal-12.pdf Sedlacek, W. E. (2004). Beyond the big test: Noncognitive assessment in higher education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422– 445. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422 Taylor, P. J., Russ-Eft, D. F., & Chan, D. W. L. (2005). A meta-analytic review of behavior modeling training. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 692–709. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.4.692 Zhao, H., & Liden, R. C. (2011). Internship: A recruitment and selection perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 221–229. doi:10.1037/ a0021295 Received April 8, 2011 Revision received July 18, 2011 Accepted August 25, 2011 䡲