Mapping Prisoner Reentry: An Action Research Guidebook

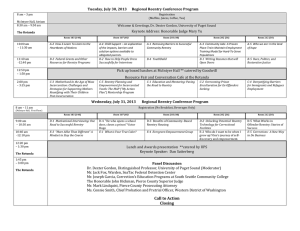

advertisement