The Dimensions, Pathways, and Consequences of Youth Reentry

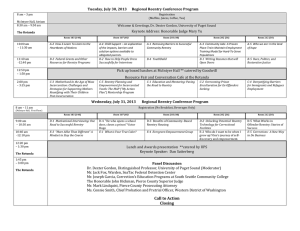

advertisement