360 Degrees of Human Subjects Protections (HSP) in Community Engagement Research (CEnR)

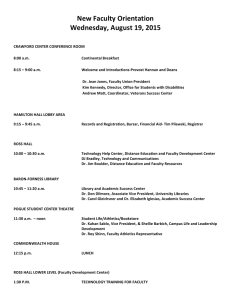

advertisement

360 Degrees of Human Subjects Protections (HSP) in Community Engagement Research (CEnR) Lainie Friedman Ross, MD, PhD University of Chicago © Ross, 2010 Funding/Acknowledgements FUNDING: This project has been funded in whole with Federal funds from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), through the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program (CTSA), part of the Roadmap Initiative, Re-Engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise, UL1RR024999. The 3 manuscripts were approved by the CTSA Consortium Publications Committee. CO-AUTHORS: Lainie Friedman Ross, MD, PhD, Allan Loup, Robert M. Nelson, MD, PhD, Jeffrey R. Botkin, MD, MPH, Rhonda Kost, MD, George R Smith, Jr, MPH, Sarah Gehlert, PhD © Ross, 2010 DISCLOSURES I have no relevant financial relationships with the manufacturer(s) of any commercial product(s) and/or provider(s) of commercial services discussed in this CME activity. I do not intend to discuss an unapproved/investigative use of a commercial product/device in my presentation. © Ross, 2010 Methodology A seven-member writing team to develop a framework for HSP in CEnR One academic researcher who does community-based participatory research (CBPR) One community research partner; Four with specialization in human subjects protections (HSP) 3 who self identify as ethicists 1 research subject advocate (RSA); One research associate with interest in HSP. Two stakeholder meetings were held with numerous academic researchers, community research partners, community activists and other HSP program personnel. At the first meeting, the stakeholders were asked to give presentations about the process, challenges and benefits of CEnR from their various perspectives. There were both large group and small group break-out sessions to give all Over the next 4 months, through iterative collaboration, the writing group developed a taxonomy and framework for the risks presented by CEnR. At the second stakeholder meeting, some changes in stakeholder participants to increase the diversity of viewpoints. All stakeholders were asked to comment on written drafts and most were asked to give oral presentations regarding strengths and weaknesses of the framework. © Ross, 2010 Traditional Conception of Human Subjects Protection (HSP) Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Title 45 Part 46 (1981, rev. 1991, 2001) outlines federal policy for the protection of human subjects in research Based on The Belmont Report (written by National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research) Three Principles Respect for persons Beneficence Justice Application Informed Consent Assessment of Risks and Benefits Selection of Subjects Establishes mandate for Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) Discusses additional protections for vulnerable populations (pregnant women, human fetuses, neonates, prisoners, and children) © Ross, 2010 The Limits of the Fed Regs The Federal Regulations were designed for clinical trials… Do not consider risks for communities The regulations also state that “The IRB should not consider possible long-range effects of applying knowledge gained in the research (for example, the possible effects of the research on public policy) as among those research risks that fall within the purview of its responsibility.” §46.111 a2 BUT there are other mechanisms to promote HUMAN SUBJECTS PROTECTIONS © Ross, 2010 Seven distinct entities may be involved in an HSP program* 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. The individual investigators* The institutional review board (IRB)* Research ethics consultation (REC) Research subject advocate (RSA) Conflict of Interest Committee Data safety monitoring plan (DSMP)* Data safety monitoring committee (DSMC) 7. Community Advisory Board *These are federally regulated © Ross, 2010 Greg Koski will discuss these The Nine Key Functions 1. The risks of the research are minimized; 2. The risks to subjects are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits; 3. The selection of subjects is fair; 4. Each participant gives a voluntary and informed consent; 5. When appropriate, the research plan makes adequate provisions for monitoring the data collected to ensure the safety of subjects; 6. There are adequate provisions to protect the privacy of subjects and to maintain the confidentiality of data; 7. Conflicts of interest are transparent and appropriately managed; 8. Consideration is given to what additional protections, if any, are needed for vulnerable populations; and 9. Proper training in human subjects protections is provided for research personnel. Again, Greg Koski will discuss these © Ross, 2010 In CEnR, the same 7 entities and the same 9 key functions must be addressed by a HSP program. What changes is the greater need to consider the risks to the community that is both research partner and research participant. © Ross, 2010 What other HSP issues need to be addressed in CEnR? Risks not only of individuals, but also of groups and communities Potential risks to non-participant members of the group What is the significance of the role of the group (community) as both research partner and research subject? © Ross, 2010 What is Community? Group versus Community Both have shared trait (for example, based on geography, but also culture, ethnicity, education, disease) Community = Structured groups Has its own internal structure and leadership Unstructured groups Internal: Can be empowered to create structure External: By a CBO Legitimacy of the structure may depend on the extent to which the leadership is inclusive and responsive. © Ross, 2010 A Taxonomy of Risks LEVEL OF RISK Individual [A] Individual by group association [B] Process Risks to Well-Being Outcomes Risks to Well-Being Risks to Agency Clinical and Clinical and psychosocial risks of psychosocial risks of the research interaction research findings Risk of undermining personal autonomy/ authority Clinical and psychosocial identity risks of the research interaction Risk of group decisions undermining personal autonomy/authority. Risk of individual decisions undermining group autonomy/authority Community Risks to group cohesion or structure [C] because of engagement in research © Ross, 2010 Clinical and psychosocial identity risks of research findings Risks to group Risk of undermining the cohesion or structure group’s moral and because of research sociopolitical authority findings A-Level (Individual Risks) Box A-1 : In a research interaction there are physical and psychosocial risks to participating individuals. Blood is drawn for a sample; there is a risk of bruising. A drug is administered; there is a risk of adverse effects. A survey is performed; there is a risk of emotional distress. Box A-2: When the findings of research conducted on individuals are reported, there are clinical and psychosocial risks to those individuals. A patient experiences adverse clinical effects from a trial and her condition is worsened. There is the risk that she will no longer be able to take a particular alternative treatment. A participant is informed she has tested positive for a genetic predisposition. There is the risk that she will incur psychological difficulty or damage to her social relationships. Box A-3: When an individual participates in research, there are risks to the individual’s moral agency. Blood samples are taken as data for a cholesterol study to which the participant has agreed; but the samples are then used as controls for a genetic study on aggression without her knowledge—an area of genetic study that she does not support. © Ross, 2010 A Taxonomy of Risks LEVEL OF RISK Individual [A] Individual by group association [B] Process Risks to Well-Being Outcomes Risks to Well-Being Risks to Agency Clinical and Clinical and psychosocial risks of psychosocial risks of the research interaction research findings Risk of undermining personal autonomy/ authority Clinical and psychosocial identity risks of the research interaction Risk of group decisions undermining personal autonomy/authority. Risk of individual decisions undermining group autonomy/authority Community Risks to group cohesion or structure [C] because of engagement in research © Ross, 2010 Clinical and psychosocial identity risks of research findings Risks to group Risk of undermining the cohesion or structure group’s moral and because of research sociopolitical authority findings C-Level (Community Risks) Box C-1: When a community engages in the research process, there are risks to the group’s cohesiveness and structure. A community engages in research. Conflict arises within the community’s leadership regarding the direction and extent of the group’s participation. One leader loses respect within the group or is ousted. Box C-2: When the findings of research are reported, there are risks to the engaged group itself. Havasupai traditionally believed their origin as a people to be the Grand Canyon. Genetics revealed their origins in Asia with migration across the Bering Straight to what is now Arizona. Threat to identity. Research found evidence of elder abuse among one Navajo community. The most prevalent form of abuse cited was neglect. The findings spurred self-critique and discord within the community because of its potential adverse impact on group solidarity and social traditions. A study of an isolated genetic community in Greece identified community members who were heterozygote carriers for Sickle Cell Disease. The traditional social operation of the community was disrupted. Box C-3: When an established community (structured group) engages in research, there are risks to the group’s moral agency. The Havasupai tribe grew concerned about diabetes in their community and sought to participate in a research study to address the issue. Unbeknownst to the tribe, the researchers used these blood samples to study evolutionary biology and schizophrenia. The data may also have been shared with researchers at other institutions. The group’s agency was harmed because they had not given consent for these additional uses of its samples. The Sephardic Jewish Congregation Mikvé Israel-Emanuel (Curaçao) is the oldest synagogue in continuous use in the Western Hemisphere with a few hundred individual members. In the 1960s, the synagogue’s Board of Directors commissioned Dr. Isaac Emmanuel to write a comprehensive history of the congregation, but retained the right to prevent publication of unfavorable descriptions to protect the community as a whole and its individual members. © Ross, 2010 A Taxonomy of Risks LEVEL OF RISK Individual [A] Individual by group association [B] Process Risks to Well-Being Outcomes Risks to Well-Being Risks to Agency Clinical and Clinical and psychosocial risks of psychosocial risks of the research interaction research findings Risk of undermining personal autonomy/ authority Clinical and psychosocial identity risks of the research interaction Risk of group decisions undermining personal autonomy/authority. Risk of individual decisions undermining group autonomy/authority Community Risks to group cohesion or structure [C] because of engagement in research © Ross, 2010 Clinical and psychosocial identity risks of research findings Risks to group Risk of undermining the cohesion or structure group’s moral and because of research sociopolitical authority findings B-Level (Individual [participant and nonparticipant] by Group Association Risks) Box B-1: When an individual or group participates in research, there may be risks to an individual who can be associated with a group—both participating and non-participating individuals. In Native Hawaiian culture, blood is correlated with power. If blood samples are taken for a research study, participants may be at risk for being stigmatized by their cultural community. A study is underway exploring the high occurrence of Sexually Transmitted Infections in North St. Louis. The individual resident of North St. Louis might be associated with the STI-likelihood trait to his detriment, whether or not he participates. Box B-2: When the findings of research are reported and traits are ascribed to a group, there are risks to individuals who can be associated with the group whether or not they participate. Studies showed a prevalence of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, genes linked to breast cancer, in persons of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage. The increased risk is ascribed to any woman who self-describes as Ashekanazi Jewish, whether or not she participated in the research, and this may result in higher insurance premiums. Expatriate Native Americans maintain group association by their biological heritage. Any study of genetic factors that enrolls these individuals can produce findings that, once ascribed to the genetic group, are ascribed to all associated individuals of that group, both on- and off-reservation and in- and out-of-study. Box B-3: When a group chooses to engage or not to engage in research, there are risks of the associated individual’s moral agency being undermined. The leader of an established community has established ongoing relationships with a research institution. He hears about a project and thinks it would be great if his community participated. Members hear about the project and are not interested as they believe that there are more important health priorities. However, they feel pressured to participate given that the leader has promised the cooperation of the community. The leader of a disease group has a bad personal experience with a researcher. The researcher now proposes a research project that may be of significant benefit to the group. The leader claims it is too dangerous and refuses to provide access. The other members of the disease group are unaware of the opportunity. © Ross, 2010 A Taxonomy of Risks LEVEL OF RISK Individual [A] Individual by group association [B] Process Risks to Well-Being Outcomes Risks to Well-Being Risks to Agency Clinical and Clinical and psychosocial risks of psychosocial risks of the research interaction research findings Risk of undermining personal autonomy/ authority Clinical and psychosocial identity risks of the research interaction Risk of group decisions undermining personal autonomy/authority. Risk of individual decisions undermining group autonomy/authority Community Risks to group cohesion or structure [C] because of engagement in research © Ross, 2010 Clinical and psychosocial identity risks of research findings Risks to group Risk of undermining the cohesion or structure group’s moral and because of research sociopolitical authority findings Interpreting Risk & Agency in CBPR RISK Incommensurability of Risks (esp. between A-level and C-level) Benefit: Risk Ratio Non-Participant Third Parties (B-type harms) AGENCY The Complexity of Relationships and Agency in CBPR A-level process concerns are addressed by informed consent and respect privacy/confidentiality Agency tension between individual and group Structured versus Unstructured Groups Structure is a necessary but not sufficient condition for group agency Only structured groups can have C-level risks PARTNERSHIPS Memorandum of understanding © Ross, 2010 In CEnR, the 9 functions of Human Subjects Protections (HSP) must still be fulfilled, but a HSP program must take into account group and individual risks [process and outcome risks]; …and the additional risks that occur when the Community is both research partner and research subject (threats to individual and group agency). © Ross, 2010 Who provides the HSP? In traditional research, HSP emanated from the Academic Medical Center (AMC) In CEnR, 360 degrees of Human Subjects Protections emanates from both the AMC (IRB*, REC, COIC) and from the community (CAB) Other HSP may be joint efforts of AMC and community (role of individual investigators, the establishment of a DSMP, and possibly the RSA functions) Human subjects protection training must be developed that is culturally sensitive and linguistically appropriate for non-health care professionals. *community members are encouraged to serve on IRBs. © Ross, 2010 Concluding Remarks Community Engagement Research (CEnR) requires a broader conception of human subjects protections. We need to train those who provide HSP about how CEnR is different from traditional research. In CEnR, HSP, like the research itself, ought to use a collaborative methodology. © Ross, 2010