Document 14639419

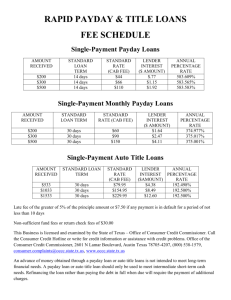

advertisement