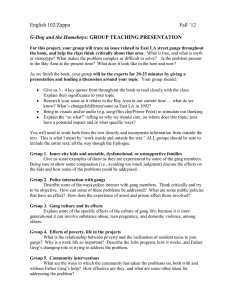

Evaluation of the Los Angeles Gang Reduction and Youth Development Program:

advertisement