Congressionally Mandated Evaluation of the Children's Health Insurance

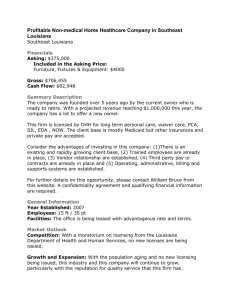

advertisement