AJS Review AJS Review: The Zionist Paradox: Hebrew Literature and Israeli

advertisement

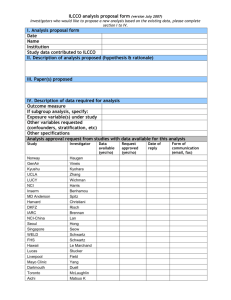

AJS Review http://journals.cambridge.org/AJS Additional services for AJS Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Yigal Schwartz. The Zionist Paradox: Hebrew Literature and Israeli Identity. Translated by Michal Sapir. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2014. 352 pp. Naomi Sokoloff AJS Review / Volume 39 / Issue 02 / November 2015, pp 480 - 482 DOI: 10.1017/S0364009415000306, Published online: 13 November 2015 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0364009415000306 How to cite this article: Naomi Sokoloff (2015). AJS Review, 39, pp 480-482 doi:10.1017/ S0364009415000306 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/AJS, IP address: 129.64.99.141 on 02 Dec 2015 Book Reviews Yigal Schwartz. The Zionist Paradox: Hebrew Literature and Israeli Identity. Translated by Michal Sapir. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2014. 352 pp. doi:10.1017/S0364009415000306 The Zionist Paradox is an English edition, somewhat abridged, of Yigal Schwartz’s 2007 book, Ha-yada‘ata ’et ha-’arez. sham ha-limon poreah. (Do you know the land where the lemon blooms?).1 Together, the English and the Hebrew titles indicate the major parameters of his study. With the word “paradox” Schwartz refers to the ferocious self-criticism that prevails alongside fierce patriotism in Israeli society. He reflects on the “gnawing self-doubts” of Israelis (1) and their pervasive sense that the Zionist endeavor, despite its extraordinary successes, has yielded an enduring sense of disappointment and missed opportunity. The Hebrew title, deliberately drawing on allusion, likewise points to a disconnect between the Zionist dream and Zionist realities. The words come from the poem “Mignon” by Goethe. In that poem, the land in question is Italy, but a character in Theodor Herzl’s novel Old New Land adopts the phrase “Do you know the land where the lemon blooms” to refer to ’Erez. Yisra’el. That is to say, Herzl’s character imagines Zion more than he has lived it; his connection to the land is highly mediated by idealized visions, hence tenuous. Even in so foundational a text as this, Schwartz identifies doubts about the possibility of actualizing the Zionist project. Note, too, that the Hebrew title quotes a literary text embedded within another literary text. This move reflects the importance Schwartz attributes to the ways that texts, and tropes handed down from one author to another, build up a cultural narrative—an overarching frame of references and values by which people live their lives. He relies on literature to bring into focus big ideas about the trajectory of Zionism, because, he observes, it has played such a central role in the construction of modern Hebrew culture. According to Schwartz, the unease Israelis feel about their identity and the place they call home is neither a new phenomenon nor the invention of a postZionist era. Modern Hebrew literature, since its beginnings, has expressed hesitation about the Zionist dream along with anxiety about its prospects and values. To sketch out this big picture, The Zionist Paradox focuses on five paradigmatic pieces of prose fiction: Abraham Mapu’s Love of Zion (1853), Herzl’s Old New Land (1902), “Yoash” by Yosef Luidor, Moshe Shamir’s He Walked in the Fields (1948), and Amos Oz’s “Nomads and Viper” (1963). (Herzl, of course, composed his novel in German, but the Hebrew translation by Nahum Sokolov appeared promptly and holds a special place of honor in Hebrew literature.) In order to assess how each of these works approaches their common concern (the renaissance of the people of Israel in the Land of Israel), Schwartz considers the treatment of two core issues: human engineering and landscape conceptualization. The first term includes romance and marriage plots. Discussion of it poses the 1. Ha-yada‘ata ’et ha-’arez. sham ha-limon poreah.: Handasat ha-’adam u-mah.shevet ha-merh.av ba-sifrut ha-‘ivrit (’Or Yehuda: Kinneret-Zmora Bitan-Dvir, 2007). 480 Book Reviews question: Who will match up with whom in order to procreate and produce the next generation as the Jewish people returns to its ancestral homeland? The second term refers to the treatment of space, and discussion on this topic includes such questions as: Where do the characters go? What ground do they cover geographically? Do they gravitate to open spaces or claustrophobic ones? What appears in the foreground, and what is relegated to background? What does all this information tell us about the values attached to exile and homecoming, urban spaces and rural settings, utopias and facts on the ground? Schwartz highlights “vectors of desire” (4) as a topic that connects love stories to space; he asks, Who longs for Zion, who for lands of their birth, who for Jews, who for non-Jews? In each of the canonical texts he explores, Schwartz uncovers surprising doubts and dreads about Zionism. Take, for example, Shamir’s He Walked in the Fields. Both as a novel and as a stage production, this work was hugely popular in its day and Shamir was long touted for creating the quintessential sabra character: Uri, the kibbutznik. The Zionist Paradox, though, argues that Uri is not a success, but an emotional failure, a “dud,” even (283). His death in battle, long celebrated by many readers as a noble sacrifice, should instead be understood as a deliberate suicide, the act of a man who cannot live up to the ideals he is expected to represent. Furthermore, Uri never feels at home, never establishes a strong or natural connection to the earth he tills, and, in effect, he provides evidence that the sabra itself is but a fabricated, literary figure, more of an idealized concept than an actualized experience. Uri’s death then makes way for a new chapter in the development of Israeli culture. The demise of the sabra makes room for Holocaust survivors—such as the mother of Uri’s unborn child—to shape the future. The kibbutz is renewed not through the native born, but through newcomers to the scene. These arguments tie in with larger claims that Schwartz makes. In his view, not only does a gap persist between Zion as imagined or ideologically defined, and Zion as Israelis have lived it—perhaps most significantly—Israelis cling to that gap. Following Zali Gurevitch and Gideon Aran, Schwartz frames this argument as a contrast between “Place” and “place.” He adds, then, that right-wing Israelis need to maintain disparities between the two, in order to feel reassured that the Zionist dream is still in progress. By striving to settle new territory or to bring in new recruits via the Law of Return, they constantly renew the pool of national tasks to be accomplished and so infuse themselves with a sense of purpose. Leftwing Israelis, for their part, are dogged by the feeling that their state is not the state they dreamt about, and they consequently long for elsewhere. They never feel normalized, never say “we are at home, we are here,” and in novels they yearn romantically for Others outside their borders (often Europeans and often Arabs). Writers frequently feel that their bodies are in the East but their hearts are in the West. Beyond these core ideas, which provide the chief armature for Schwartz’s study, The Zionist Paradox delves into close readings of the texts. In the process, it draws on a range of theoretical models. Especially engaging is the analysis of space. In recent years space has become a hot topic in Hebrew literary and cultural studies—thanks, in no small part, to Schwartz. He took a leading role in 481 Book Reviews this subfield through his brilliant discussions of landscapes and topography in the writing of Aharon Appelfeld.2 Now, in this volume, he provides sensitive new perceptions of familiar texts through cartographic readings that follow characters as they move around their storyworlds.3 However, analysis of space does not stand alone as a critical approach here. In addition, Schwartz draws on postcolonial criticism; explores ideas about mythology developed by Mircea Eliade and Joseph Campbell; integrates discussion of animal imagery; and places Mikhail Bakhtin in conversation with all the above perspectives. This book’s central argument—that modern Hebrew literature is riddled with ambivalence about the Zionist project—will resonate with anyone who has tried to teach this literary corpus in translation to an audience outside Israel. It can be colossally difficult to illustrate the main tenets of Zionism through literary texts. Even the most canonical ones, the pieces most often anthologized and included on university syllabi (think, for example, of H.ayim Hazzaz’s “The Sermon,” S. Yizhar’s “The Captive,” and A. B. Yehoshua’s “Facing the Forests”) present abundant self-critique, inner contradictions, and stances opposed to mainstream consensus. Popular culture, such as Hebrew songs and TV shows, may display simpler, more straightforward, or at least less contorted views and so more clearly reflect majority opinions and centrist assumptions. The Zionist Paradox, though, focuses intentionally on preeminent writers and their complexities. Schwartz aims to challenge well-established readings and offer new insights into classic texts, not to take a comprehensive look at the whole of Israeli culture. This study, then, can help readers appreciate the special role of Hebrew literature in Israeli society and the ways it has tussled mightily with multifaceted issues of identity and purpose. Indeed, this literature has been a central address for such intellectual heavy lifting. As Schwartz notes emphatically, “a considerable part of the characteristics of modern Hebrew culture was thought up and shaped in the feverish minds of Hebrew writers. …” Moreover, he observes, from the end of the eighteenth century on, those writers “gained among large publics a status enjoyed in the distant and recent past by the nation’s great intellectuals and spiritual figures: prophets, priests, rabbis, and tzadikim” (3). Schwartz’s book presents richly detailed and at times demanding close readings of texts that have had tremendous impact and continue to reward careful scrutiny. It’s well worth it to foray into the intricacies of his analysis. Naomi Sokoloff University of Washington Seattle, Washington • • • 2. See, especially, Aharon Appelfeld: From Individual Lament to Tribal Eternity (Hanover, NH: Brandeis University Press, published by University Press of New England, 2001). 3. Delightful maps of those storyworlds, prepared by Yifaʿat Hecht, illustrate the original Hebrew version of the book. Unfortunately, they do not appear in the English edition. 482