in guatemala ADOPTIONS Protection or business?

advertisement

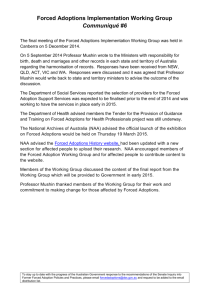

ADOPTIONS in guatemala Protection or business? This study entitled Adoptions in Guatemala: Protection or business? was prepared with contributions and assistance from several persons, institutions and organizations, which shared their time, opinions, vision or contributions with us. We extend our sincere thanks to all of them. Adoptions In Guatemala - protection or business? Casa Alianza Foundation Myrna Mack Foundation Survivors Foundation Social Movement for the Rights of Children and Adolescents Human Rights Office of the Archbishop of Guatemala (ODHAG) Social Welfare Secretariat (SBS) Produced in Guatemala Design by Tritón imagen & comunicaciones Printed by Tipografía Nacional First edition: November 2007 2 Table of Contents Introduction 5 Chapter 1 9 Legal Framework Chapter 2 17 Adoptions in Guatemala 1. International adoptions 1.1 Characteristics of boys and girls in the process of being adopted 24 29 1.2 Geographic design contemplated for boys and girls in the process of being adopted 33 1.3 Adoption network in Guatemala 35 2. Trafficking in girls and boys 45 2.1 Theft and disappearances of girls and boys 46 2.1.1 Victims 46 2.1.2 Who is guilty of children’s theft, kidnapping, disappearance 49 2.1.3 Modus operandi 50 2.1.4. Areas where the crime is committed 2.1.5 52 Response by public authorities, civil society organizations and communities 53 2.2 Purchase and sale of children 56 2.2.1 Victims 56 Who is responsible for the purchase of children 58 2.2.3 Modus operandi 58 2.2.4 Places where the crime is committed 60 2.2.5 Response by public authorities, civil society organizations and communities 61 Chapter 3 63 Conclusions 3.1 Adoption 63 3.2 From adoption to adoption networks 64 3.3 From trafficking in children to adoptions 68 3.4 From trafficking in children to adoptions to the murder of women 72 Chapter 4 73 Suggestions Bibliography 76 4 Introduction Introduction Adoption as such contributes to the welfare of girls and boys who lack the protection and support of a family. In this regard, adoption must continue and be strengthened, because it is something that helps give an orphan, an unwanted, indigent or abandoned girl or boy a home. All boys, girls and adolescents are entitled to be raised and educated by their families and, exceptionally, by foster families. Whenever that is the case, the State is under the obligation to guarantee that adoptions are in the child’s best interest, and to this end it must base its actions on national laws and international instruments ratified by the Guatemalan State in the area of children’s protection. However, the Guatemalan State has been unable to ensure the legality of adoption procedures, thus turning this noble institution into a profitable business. In this business, the children who are given up for adoption are not those who need it most, but those conceived for that purpose. Babies, both boys and girls, are traded. Infants are demanded for adoption by foreign families, in whose consumer-minded societies their future sons and daughters have a price and can be bought. In Guatemala there are networks of “child traffickers” who offer and negotiate babies, and not only those given up voluntarily for adoption, but also as a consequence of coercion and deceit, theft and kidnapping. These two extremes have resulted in a market where Guatemalan girls and boys are bought and sold as if they were simple merchandise. doptions in Guatemala - protection or business? The legal and legitimate adoption procedure includes the provisions of the Law for Integral Protection of Children and Adolescents (LPINA) and those of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. In both instruments, children’s best interests prevail. To this date, the Guatemalan State does not comply with the provisions of the national and international legal framework, because adoptions are processed according to the Law on Notarial Proceedings Governing Voluntary Jurisdiction Matters, in the implementation of which economic interest and not the child’s best interests have prevailed, and because this law should have been tacitly repealed from the time the LPINA Law entered into effect. That is the reason for this investigation, which reviews the issue of adoptions in Guatemala, based on files and statistics taken directly from public institutions to ensure objectivity in the analysis and statement of the facts. The investigation gives an overview of the adoption procedure and how it does not confer protection and assurances to girls and boys given up for adoption, but rather violates their human rights and their right to a safe adoption under State surveillance. The outcome reveals the illegality of adoption procedures, irregularities in adoptions, the existence of a criminal economy surrounding adoptions, the operations of n child-trafficking networks and a baby market. These situations point to the assumption that adoptions in the country are linked to organized crime and that they are often carried 6 out with the consent of Guatemalan Government and justice officials. In order to prevent and eradicate baby trafficking for adoption purposes, the Guatemalan State must fulfill its obligation to attack the root causes of the problem and guarantee the legality of adoptions. Currently there are State institutions that are making efforts to regularize and legalize adoptions, particularly international ones, such as the First Lady’s Social Welfare Secretariat (SOSEP), the Social Welfare Secretariat (SBS) and the National Civil Police (PNC), which are working in coordination with the Multisectoral Working Group on Adoptions to document current adoption practices to learn about the operational system and to develop strategies that promote good institutional practices. On its part, the Multisectoral Working Group on Adoptions, which includes the social movement, the religious sector, international cooperation and State agencies responsible for the protection of children’s rights have been instrumental in the participative drafting of Bill 3217, based on the principles of the Convention on the rights of the Child, the Convention on the Protection of Children and Cooperation on the issue of International Adoption and the Law on Integral Protection of Children and Adolescents. The social movement, in turn, works for the rights of children and adolescents and is made up of fifty civil-society organizations. These efforts are complemented by the work done by civil-society organizations such as Casa Alianza and Survivors’ Foundation, which carry out important research and legal follow-up work of cases that have led to fact finding, in some cases obtaining judicial decisions in favor of women victims and the recovery of babies that had been stolen and bought to be given up for adoption. Performance of State institutions’ functions should also concentrate on criminal prosecution and punishment of the crime of trafficking in children as such. This requires decisive work on the part of the Judiciary, the Ministry of Justice and the police. The office of the Prosecutor General of the Nation must also perform its function of protecting children and ensuring the legality and legitimacy of adoption procedures. The results of this study indicate that Guatemala should conscientiously determine what it means to respond to the demand for international adoptions. Based on the results, the Guatemalan Government and society should find mechanisms to attack the causes of illegalities in adoptions and make it clear that Guatemalan girls and boys are not merchandise. Chapter 1 Legal Framework Legal Framework Legal Framework International treaties, conventions and conventions, as well as domestic law, constitute a regulatory framework on the protection of girls and boys that are given up for adoption. In 1986, the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted the “Declaration on the Social and Legal Principles Regarding the Protection and Welfare of Children, with Special Reference to Adoption and Placement in Foster Homes, at the national and international levels”. This Declaration establishes that when the child’s parents are unable to take care of him or when their care is unsuitable, the possibility of placing the boy or girl under the care of other family members or an adoptive family or an appropriate institution must be considered (article 4) and that international adoption will only be considered when these conditions cannot be offered in the country of origin as an alternative way of providing him or her with a family (article 17). It also establishes four fundamental questions: one, that the child’s birth parents and the future adoptive parents must have enough time and suitable counseling to reach a decision on the child’s future (article 15); two: the prohibition of kidnapping or any other act for the illicit placement of girls and boys (article 19); three: the importance of preventing adoptions from producing financial benefits for those who take part in processing them; and four, protection of children’s legal and social interests (article 21). This international declaration provides the Guatemalan State with principles that allow it to interpret the law. Jurisprudence is also created as more and more countries implement it. adoptions in guatemala - protection or business? Three years later, in 1989, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which establishes that “in all the measures concerning children taken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, a main consideration will be the child’s best interest” (article 3). Since this Convention recognizes that girls and boys must grow up in a family, surrounded by an atmosphere of happiness, love and understanding to achieve their full and harmonious development, it has considered special rights to protection and assistance for children deprived of this family environment. When considering alternative homes for these girls and boys, the Convention establishes that special attention must be given to continuity in a child’s education and to aspects having to do with his or her ethnic, religious, cultural and linguistic origins. On adoption, it establishes: one, that adoptions shall be authorized by competent authorities and respecting legal and legitimate procedures; two: that they will be carried out with the full knowledge and consent of the birth mothers and fathers, family members or guardians or the girls and boys, for which they will have received the necessary counseling; three: international adoptions will be considered advisable when girls and boys cannot be properly cared for in their country of origin; four, that girls and boys given up for adoption in foreign countries must enjoy the same rights as other nationals of that country; five, that international adoptions must not produce undue financial benefits for those who participate in them; and six, that care must be taken to ensure that the placement of the boy or girl in another country is carried out through competent authorities or bodies, under bilateral or multilateral agreements (articles 20 and 21). The Convention also stipulates that States parties should “take all the national, bilateral and multilateral steps that are necessary to prevent the kidnapping, sale or trafficking of children for any purpose or in any form (article 35). The Convention on the Rights of the Child was adopted by the Congress of the Republic of Guatemala on May 10, 1990, through Legislative Decree 27-90. It was likewise adopted by other countries such as El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, Peru, the Dominican Republic and Paraguay. By 2007, the Convention had been ratified by 192 and only the United States of America and Somalia had failed to do so.1 Said Convention paves the way for regulation of international adoptions, which coincides with the increase in the demand for Latin American girls and boys to be adopted by families in developed countries. This situation degenerates into a disaster. State control of adoption proceedings becomes inoperative and even becomes an accomplice of the child trafficking networks. Because of these irregularities in international adoptions, the issue of protection for girls and boys who are given up for adoption was taken up again in The Hague in 1993. 1 www.unicef.org (30/10/2007) 10 Thus, the Convention on Protection of Children and Cooperation in the Question of International Adoption was approved on May 29 of that year. Its objectives are: one, to ensure that international adoptions are carried out considering the best interests of girls and boys and respect of their fundamental rights; two, to establish a cooperation system among the States parties to ensure this protection and prevent the kidnapping, sale or trafficking of girls and boys; and three, to ensure that adoptions are carried out based on the rules established in the Convention (article 1). This Convention establishes that international adoptions may only take place when (article 4): (a) it has been established that the girl or boy is adoptable; (b) it has been determined that the girl or boy cannot be placed in his or her country of origin and, then, international adoption is in the child’s best interests; (c) it has been ascertained that the persons, institutions and authorities whose consent is required for the adoption have been appropriately counseled and informed on the consequences of their consent to the girl’s or boy’s adoption; this consent must be given freely, legally and in writing and not be obtained in exchange for payment or compensation. In the mother’s case, consent is only accepted when given after the birth of the baby and not before; and (d) Steps have been taken to ensure that girls and boys with a certain degree of maturity have been counseled and informed on the consequences of the adoption, their opinions and wishes have been taken into account, they have given their consent freely, legally and in writing. Also in this case, consent cannot be given as a result of payment or compensation. On the other hand, the Convention considers that adoptions may only carried out when the competent authorities of the receiving State have made sure that the future adoptive parents are suitable and capable of adopting; that they have received adequate counseling; and that the girl or boy has proper authorization to enter and permanently reside in the receiving country (article 5). It also establishes that all contracting States to the Convention must designate a Central Authority responsible for fulfilling the obligations established by the Convention for protection of the rights of children with regard to international adoption (article 6). The Central Authority is administrative, not jurisdictional, and is located in the State; one of its functions, however, is to cooperate and coordinate with the judicial and other competent authorities to ensure the welfare and safety of an adoptable boy or girl. However, protection of children with regard to international adoptions will depend on the number of countries that ratify this Convention and of the quality of its implementation. Several comments are in order in this respect. The first one is that in Guatemala, the Convention will enter into effect as of December 31, 2007, but the United States, for instance, which is the country that has the highest demand for Guatemalan girls and boys for adoption, continues to delay its ratification. To this we must add the pressures exerted on Guatemala to conclude the international adoption procedures begun in 2007 before the entry into effect of the Convention. The second one is that the Guatemalan State must delegate the Central Authority of the Convention to an instuitution whose transparency and incorruptibility cannot be placed in doubt, and the country faces an enormous challenge in that regard, if one considers that most of its institutions are linked to irregular adoption procedures. 11 adoptions in guatemala - protection or business? The third one is that the Convention, like the 1986 Declaration and the Convention on the Rights of the Child of 1989, prohibit undue financial benefits for those who participate in adoptions, but it also imposes more specific restrictions when it stipulates that “only costs and expenses may be charged, including reasonable fees for the persons who have played a role in the adoption. Directors, managers and employees of interested organizations who take part in the adoption procedure may not receive disproportionate compensation for the services rendered” (article 32). This means that proper implementation of the Convention could leave a considerable number of persons who are involved in the child trafficking networks without benefits. In other words, these networks are on the alert and will do everything in their power to weaken implementation of the Convention and will likely do so from the very Central Authority designated by the Government of Guatemala. Thus it is essential for a Council or Group made up of civil society organizations to audit the actions of the Central Authority with the assistance of international cooperation. Regarding this last point, it must be remembered that the State of Guatemala also ratified the Protocol for the Prevention, Repression and Punishment of Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, that complements the United Nations Convention on Transnational Organized Crime.in August 2003 (Decree Number 36-2003). The Guatemalan State is therefore under the obligation to “prevent and combat trafficking in persons, giving special attention to women and children; protect and assist the victims of trafficking , respecting their human rights, and promote cooperation among States to achieve these purposes” (article 2). It specifically establishes that “collecting, transporting, transfering, harboring or receiving a child for exploitation purposes is considered to constitute trafficking in persons, although none of the means enumerated is used”; these include sexual abuse, forced labor, servitude, slavery and organ harvesting (article 3). Thus, one of those means that are not listed is the trafficking of children for adoption purposes, since in Guatemala traffickers resort to threats, the use of force, coercion, kidnapping, fraud, deceit, abuse of power, abuse of a situation of vulnerability and receiving or making payments or other benefits to obtain the consent of the person who has the guardianship of the boy or girl in their collection, transportation, transfer, lodging or receipt. In the national legal framework, adoption is contemplated in article 54 of the Constitution of the Republic of Guatemala, which stipulates that 12 the protection of orphan or abandoned girls and boys is a matter of national interest and that an adopted child becomes the son or daughter of the adopter. This article recognizes that adoption is a measure to protect and give a family to girls and boys who do not have one. The adoption process itself is governed by the Civil Code of September 14, 1963, which defines adoption as “the legal act of social welfare whereby the adopting parent takes a child that is the offspring of another person as his own child” (article 228). According to this Code, adoption only affects the adopter and the adoptee (article 229). The process can begin with the application for adoption filed in the Court of First Instance of the place of residence of the adopter. The child’s birth certificate and the testimony of two honorable persons who attest that the financial and moral status of the adopter qualify him or her as capable of meeting the obligations an adoption entails (article 240) should be submitted. In view of the implementation of the provisions of this article, most girls and boys are registered in the Municipality of Guatemala, even if they were born in other parts of the country. On the other hand, the process stipulated in the Civil Code lends itself to other anomalies such as documents lacking authenticity or failure to counsel the birth mothers and fathers so they can give informed consent to the adoption or to preclude the possibility of consent being given as a result of deceit, coercion or purchase. The rights and guarantees the State must ensure for all boys or girls in the adoption process are also not ensured. Other aspects the Civil Code addresses are cessation, reversal and rehabilitation of parental custody. Aspects that have to do with the rights of the child and his or her mother and father are not dealt with. In 1977 , the Congress of the Republic of Guatemala enacted the Law Regulating Notarial Processing of Matters falling under Voluntary Jurisdiction (Decree number 54-77). Under this law, adoptions regulated by the Civil Code may be formalized by a notary public without prior judicial approval of the proceedings (article 28). This means that a judicial decision is not required for adoption, but only approval by the competent authority, which is currently the office of the Prosecutor General of the Nation by means of a public instrument executed by a notary public. This Law has given rise to multiple violations of the rights and guarantees of girls and boys given up for adoption, since there is no control of adoption procedures by the competent authorities and the children given up for adoption in other countries are not followed up. Thus, this provision has resulted in a drop in judicial adoptions, which only represent 2% of the total, the remaining 98% being processed extrajudicially or by notaries public. The notarial procedure requires the birth certificate of the child, the testimony of two honorable persons who attest to the financial and moral status of the adopters, a report by a social worker of the Family Court and protection of the assets of the adoptee, if any. Then the office of the Prosecutor General of the Nation formalizes the adoption through a public instrument and if there are any objections they should be expressed in a timely manner. The Law on Integral Protection of Children and Adolescents (LPINA), in force since July 18, 2003, stipulates that “the parents’ or the family’s lack of material resources does not constitute sufficient grounds for the loss or suspension of parental custody”. Therefore, children must remain with their birth families. The State is under the obligation to create institutions, facilities and services to promote family unity and provide appropriate assistance to parents, relatives or custodians for the upbringing and care of girls and boys (article 21). This Law recognizes the institution of adoption, provided that priority is given to the best interests of girls and boys and adolescents and that it is carried out in accordance with the treaties, conventions, conventions and other instruments on this matter adopted and ratified by Guatemala (article 22). 13 adoptions in guatemala - protection or business? With regard to international adoptions, it stipulates that it is the duty of the State to ensure that girls, boys and adolescents enjoy the same rights and standards that exist in their country of origin and and are subject to the procedures established by the law on adoptions (article 24). It should be stressed that when the LPINA law entered into effect, everything stipulated on adoptions in the Civil Code and the Law Regulating Notarial Proceedings in Matters falling under Voluntary Jurisdiction should have been repealed since, under the principle of supremacy, the most recent provision repeals the earlier one, whether expressly or tacitly. In this case, LPINA went into effect in 2003, whereas the Civil Code dates back to 1963 and the Law to 1977. One can conclude, therefore, that adoptions processed through notarial proceedings are illegal. In addition to this, the special protection provisions contemplated by LPINA to preserve the family unit are being violated by the State of Guatemala and, therefore, notarial proceedings authorized by the office of the Prosecutor General of the Nation does not result in loss of parental custody of a girl or boy given up for adoption. As pointed out by the Inter American Commission on Human Rights of the Organization of American States2,, due to the lack of State control and the high prices paid by adopters, instead of providing an appropriate solution for orphan or abandoned children, adoption gives rise to child trafficking networks. Given the weakness and shortcomings of Guatemalan administration of justice (…), these networks currently operate with total impunity in the country and, according to reports received (…), the State participates and/or condones their activities”. In this regard, the study carried out by the Latin American Institute for Education and Communication (ILPEC) at the request of UNICEF concludes that the adoption process follows the “laws of supply anhd demand”, the outcome being child 3 trafficking. 2 (2003) Chapter VI, The Situation of Children. 3 Latin American Institute for Education and Communication, ILPEC (2000). Adoption and children’s rights in Guatemala. UNICEF. Guatemala. 14 Principles of supremacy Principle of hierarchy. Article 46 of the Constitution of the Republic of Guatemala, which deals with the preeminence of international law, stipulates that “in the area of human rights, treaties and conventions adopted and ratified by Guatemala have precedence over domestic law”. The State of Guatemala is violating the Convention on the Rights of the Child since it does not safeguard the best interest of children given up for adoption through the Law Regulating Notarial Processing of Matters falling under Voluntary Jurisdiction. Although it could be argued that the Constitutional Court concluded that the Constitution has precedence over the international legal framework, the latter has precedence over any other law of the country. In this regard, the Constitution establishes that social interest prevails over private interest and that laws and government or other decisions that curtail, restrict or distort the rights guaranteed by the Constitution (article 44) are void ipso jure. Thus, the Law Regulating Notarial Processing of Matters falling under Voluntary Jurisdiction is not applicable to adoptions because the child is being treated as the object of a transaction and not as a human being with rights inherent to human beings, whose protection is constitutionally assured. The principle of superiority. This principle states that the latest law that goes into effect expressly or tacitly repeals preceding ones. Thus, the provisions of the Civil Code of 1963 and the Law Regulating Notarial Processing of Matters falling under Voluntary Jurisdiction of 1977 are tacitly repealed by the provisions of the Constitution of the Republic of Guatemala of 1985, the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Law on Integral Protection of Children and Adolescents of 2003, especially with regard to the best interests of the child. Constitution of the Republic of Guatemala, 1985 Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989 Principle of superiority Law on Integral Protection of Children And Adolescents, 2003 Law Regulating Notarial Processing of Matters falling under Voluntary Jurisdiction, 1977 Civil Code, 1963 Principle of specialization. This principle means that if there is a special law on the subject, it should prevail. In this sense there is the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Law on Integral Protection of Children and Adolescents, both specializing in the protection of children’s human rights. The Law Regulating Notarial Processing of Matters falling under Voluntary Jurisdiction does the opposite. 15 Chapter 2 adoptions in guatemala – protection or business Adoptions in Guatemala in Guatemala The previous chapter established that there is an international and national legal framework on adoptions. However, although Guatemala has the Law on Integral Protection of Children and Adolescents and has ratified all the international agreements on the subject in the international framework and more recently adopted the Convention on Protection and Cooperation in the Area of International Adoptions, there is still illegality in the fact that any notary may personally process an adoption. This illegality is possible because the State does not fulfill its obligation to guarantee legal adoptoin based on the prevalence of the child’s best interests. Added to this is the 2003 decision of the Constitutional Court of Guatemala in 2003, which stated that the decree adopting the Convention on Protection and Cooperation in the Area of International Adoptions was unconstitutional. This made it possible for notarial adoptions to continue with very little State participation and presence4. The recent ratification of this Convention in 2007 shows the interest the State of Guatemala has in regulating adoptions. It is worth mentioning that the State does have the necessary legal instruments to repeal the Law Regulating Notarial Processing of Matters falling under Voluntary Jurisdiction and to protect the human rights of girls and boys given up for adoption. Guatemala is one of the few countries in the world, if not the only one, where an adoption can be processed by a notary public. 17 adoptions in guatemala - protection or business? Accession by Guatemala to the Hague Convention on Protection and Cooperation in the Matter of International Adoption In 2002, the Congress of the Republic of Guatemala adopted the Convention on Protection of Children and International Cooperation in the Matter of International Adoption (hereinafter called the Hague Convention) through decree 50-2002, which should have entered into force on March 2003. However, its validity was challenged by a group of notaries interested in preserving the existing adoption system and the Constitutional Court stated that the process of accession to the Convention was unconstitutional. On February 28, 2007, the President of Guatemala issued Government Resolution number 64-2007, which withdraws all the reservations made by the Republic of Guatemala in 1969 to articles 11 and 12 of the Vienna Convention on Treaty Law, which was confirmed again in 1997. After this reservation was removed, on May 22, 2007, the Congress of Guatemala ratified the Hague Convention through Decree 31-2007. The entry into force of this convention was to take place on December 31, 2007. On July 13, 2007, the Social Welfare Secretariat of the Presidency was designated as the Authority of the Hague Convention through Government Resolution No. 260-2007. Its mandate to enforce this Convention begins on December 31, 2007 and its activities will be coordinated with the competent agencies, namely the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Solicitor General, the Judiciary, the Ministry of the Interior and the Prosecution. This situation has made Guatemala the fourth country in the world in number of boys and girls supplied for international adoptions after Russia, China and South Korea. It ranks number one with respect to the total population, i.e. the ratio between the number of citizens and the number of boys and girls given up for adoption4. For example, 37 children were adopted for every 100,000 inhabitants in 2006. In that same year, one of every 100 children born in the country was given up for adoption. In 2003, six countries decided to impose a moratorium on Guatemalan adoptions due to irregularities in the process. Some of the reasons that led to this decision were: UNICEF reports, reports by Casa Alianza and by the Human Rights Office of the Archbishopric on the trafficking of Guatemalan children for international adoption; the late accession of Guatemala to the Hague Convention in 2002, that is, nine years after it was adopted in 1993; and the 1993 Court of Constitutionality decision that accession to that instrument was unconstituional. Those countries were Spain, France, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Germany and Canada, all of them parties to The Hague Convention. 4 Latin American Institute for Education and Communications, ILPEC (2000). Adoption and the Rights of Children. UNICEF. Guatemala. 18 However, other countries, particularly those that have not acceded to The Hague Convention, continue to process adoptions in Guatemala. Such is the case of the United States, where more Guatemalan children are adopted than from any other country in the world after China. The situation is sensitive, if you bear in mind that China has 1,300,000,000 inhabitants while Guatemala has 13,000,000 and that 97% of the Guatemalan children given up for adoption in 2006 went to U.S. families. Adoptions increased significantly in the early part of the eighties, during the internal armed conflict, when many orphaned, lost or abandoned boys and girls were given up for adoption. According to the National Commission for the Search for Missing Children, close to 5,000 girls and boys disappeared, were separated from or given in adoption during this period. By 2003 this Commission had documented 1,084 cases of missing children, of which 46%, or 500, were babies under one year of age who had been kidnapped and adopted. “Some of the factors that make it difficult to solve these cases are the inability to obtain information in military centers, orphanages, shelters and others, or to see the information in adoption files” 5. 5 According to information provided by CNBND representatives at the hearing organized by the Inter American Commission on Human Rights of the Organization of American States during its 118 th session on October 16, 2003. 6 Human Rights Office of the Archbishopric (ODHA). The REMHI Report: Guatemala, nunca más (Guatemala never again). Interdiocesan report on Recovery of Historic Memory, Vol. 1: Informe Interdiocesano Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica. Tomo 1: Impactos de la violencia (Impacts of Violence). Chapter II: La destrucción de la semilla (Destruction of the Seed). Title: De la adopción al secuestro” (From adoption to kidnapping). Guatemala. 7 Op. cit. Most of the time, families that took in children or adopted them in the community were part of the cohesion and solidarity mechanisms that gave family and community support to orphaned children. But taking children in was not always a solidary mechanism because there is evidence of children who were kidnapped and then used as servants by families who were not affected by violence, or children who were separated by force from their families and “reeducated” in special homes. There are also cases of children who were separated from their families or communities, kidnapped and fraudulently adopted by some of the murderers of their families.6 "Many families of Army officers have adopted children who were the victims of violence. It became a fad among Army ranks to take care of three or four year-old children who were lost in the mountains."7 Some children were “saved” from massacres to be adopted by Army officers or taken to their homes as servants. For example, a survivor of the “Dos Erres” massacre in Petén who was six at the time was taken away by one of the soldiers who participated in the murder of the village inhabitants and the members of the child´s family. One girl who was three monts old when her family was murdered in Las dos Erres was taken away and adopted by one of the soldiers. Another girl, three years of age when her family was murdered in San Gaspar, Chaju, Quiché in 1982, was taken by soldiers to Guatemala city. There she was abandoned and an Evangelical 19 adoptions in guatemala - protection or business? organization made arrangements to have her adopted outside Guatemala8. During that period, according to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and the use of children in pornography, adoption began as a possibility of finding adequate solutions for these boys and girls. However, in time, it became a profitable commercial operation, when it became evident that there was an important “market” for baby adoptions. Baby and young children trafficking was thus established as a large scale operation in Guatemala9. The uncontrolled growth of international adoptions in recent years is due to other causes as well: the economic conditions of the country, where 51 or the population lives in poverty and 15.5% in extreme poverty10, but particularly the condition of women´s economic rights. The women who are most at risk belong to the poor economic classes in rural and marginalized peri-urban areas. 56% of these women’s families are affected by poverty and have little access to health and education and, therefore, experience difficulties in preserving and/or defending their rights. Their social and cultural rights are also violated in this manner. Some of the social rights in question are the right to a family, education, security and social welfare and food. Cultural rights include the right to an individual identity and access to services in their own language. There are households headed by single mothers due to the problem of irresponsible fatherhood; 50 cases are considered each week, 70% of them to order the payment of alimony and 30% because the children's fathers have failed to pay. Paternity (and maternity) are not exclusively an economic matter: other factors provide a pleasant family atmosphere and one that allows daughters and sons to develop fully. It has been determined that single mothers are unprotected. Some of the adoption cases we have studied show that one of the most frequent reasons used to convince mothers to give their child up for adoption is a single mother’s financial need: the need for food and medicine and medical care are the most frequent ones. On the other and, women are vulnerable in the area of education and access to services in their own language. Even if they know how to read and write, they are often unable to understand and convey the meaning of information. They sign papers without really knowing what they are getting into. At hospitals and clinics they receive instructions they are unable to process and they accept thyem without understanding the consequences of their actions. There is a case of a notary public who offered a mother monetary assistance to treat a sick child. She then made the mother sign papers, allegedly from the hospital where the child was being treated. When the young mother tried to see her sick child, the notary told her that by signing those papers she had given up her child for adoption. 8 Inter American Human Rights Commission (CIDH) (06/04/2001). Chapter XII. The Rights of the Child. The effect of armed conflict on children. 9 10 Op. cit. United Nations Development Program (UNDP) (2005). National Human Development Report, Guatemala. 20 Adoptions are also directly linked to women’s sexual and reproductive rights, and especially those of young women. Statistics on maternity among young women are dramatic: of every 1,000 women between the ages of 15 and 19, 114 give birth every year; the fertility rate among rural young women is 113 per thousand and 85 per thousand among young women in urban areas. 44% of women between the ages of 20 and 24 had a child before the age of 20, and the highest proportion, 68%, is among uneducated women. It reaches 54% among indigenous women and only one-half of the mothers aged 15-24 had professional medical assistance the last time they gave birth11. The lack of access to timely information and sexual education are also major factors. “The total number of pregnancies among girl children, adolescents and young women aged 11-19 was 52,009 in 2005. Of these, 37% are reported among girls aged 15-17 and 60% among adolescents aged 18-19. These figures show the seriousness of not preventing pregnancy and how early it occurs. Only this year, there were 1,275 pregnancies among girls and adolescent aged 1114”12. This study showed that the women who are most susceptible to coercion and deceit in giving up their babies for adoption are under 25, single mothers, uneducated and without the financial resources needed to receive prenatal care and assistance during childbirth, as well as to support the child after it is born13. Violence against women is another factor that must be taken into consideration, since babies born to women who have been raped are being given up for adoption. The study identified three rape cases, in which the mothers were coerced or deceived into giving up the newborn baby for adooption. In one of the three cases, the rapist forced the woman to leave her community, took her to Cobán to work as a maid in a private house and from that house she was sent to Guatemala City to give birth and her baby girl was taken away and given up for adoption14. The Survivor Foundation identified five cases of 10 and 11-year-old girls who were raped and became pregnant. In all five cases, the girls’ families refused to give up the babies for adoption for religious reasons, since they believe that doing so is a sin. This shows, contrary to the common belief, that babies born out of rape are not rejected by their families. This situation supports the belief that deception and coercion are used to make these women give up their children for adoption. A risk factor is the “1.8% of women aged 15-24 who stated that their first sexual experience was rape, which increases to 18% among 13-year-old girls”15. In a survey conducted by the Human Rights Institute of San Carlos University of Guatemala (IDHUSAC) in 2006, 8% of the young women surveyed stated that their first sexual experience had been rape16. The vulnerable situation of women with respect to their economic, social and cultural and sexual and reproductive rights is being used by child trafficking networks that are involved in adoptions. These have encouraged the sale of babies by their own mothers and, in certain cases, by their fathers. 11 Guttmacher Institute (2006). Early Maternity in Guatemala: an Ongoing Challenge (Maternidad temprana en Guatemala: un desafío constante). Cited by Campos, X. (2007). Derechos humanos de la juventud guatemalteca. (Human Rights of Young Guatemalans). IDHUSAC, Guatemala. 12 Ibid. 13 See paragraph 2.2, Purchase and Sale of Children. 14 Case from Alta Verapaz, 2006. Defender of Indigenous Womenn (DEMI). 15 Pan American Health Office (2005). Cited by Campos, X. (2007). Op, cit. 16 Campos, X. (2007). Op. cit. 21 adoptions in guatemala - protection or business? This has also given rise to the business of surrogate motherhood, or wombs for hire, as in a case in Alta Verapaz, where a man was arrested and stated that there were several pregnant women in his house17. These individuals have also promoted the kidnapping, theft and disappearance of girls and boys. That is the case of the baby kidnapped from a tortilla store in Guatemala. When it was recovered by the police, it already had a birth certificate with another name and a notarial certificate giving custody of the child to a crèche that would give it up for adoption. The situation of kidnapped babies has resulted in a double victimization of women, who are accused by court officials of having sold their children. These women’s lives are governed by economic interests based on violence against women. This reduces a child to merchandise, which should be condemned. “Thus, the argument that in most cases adopted children end up living in much better conditions does not justify the trafficking of newborns and children in any way"19. In this regard, the State in general, and the Office of the Prosecutor General of the Nation in particular are committing an illegal act by approving adoptions when the reason for giving up the child is the “parents’ lack or absence of material resources”, since the Law on Integral Protection of Children and Adolescents stipulates that “if there is no other reason that by itself justifies this measure, girls and boys or adolescents will be kept in their birth families (article 21). One more reason for the increase in adoptions in Guatemala is international demand, especially on the part of United States families, who pay between $13,000 and $40,000 for a Guatemalan baby. “UNICEF estimates that there are 50 applicants for each healthy newborn. For a growing number of couples, international adoption has become the only viable solution. The increasing desire to adopt a child living in difficult circumstances with its birth family or in its birth community has also contributed to this increase in demand”18. However, this should not be a reason to support and accept the sale of a human being. 17 Resumen Centroamericano de Noticias (Central American News Summary), as recorded by the National Commission for the Prevention of Lynching (07/2007). 18 Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography, Ms. Ofelia Calcetas Santos (E/CN.4/1999/71). 19 22 Ibid. Ilegality in Adoption Proceedings The notary public receives the girl or boy because the mother, father or family does not have the necessary material resources to support it [This constitutes a violation of article 21 of the LPINA Law]. During the adoption proceedings, the girl or boy is placed in a creche or a private home and not in a State institution that is equipped to protect the child. 98% of the places where children are “deposited” are private houses without State authorization to operate. The same situation exists in some creches. The fact that the State fails to perform its function of supervising adoptions indicates that the State is corrupt and is acting as an accomplice. Institutions that are competent in adoption matters (approval and protection of children), safety and criminal indictment and prosecution do not fulfill their duty to protect children and guarantee their right to an adoption tht considers their best interests above all and in accordance with nationa and international legal instruments in this matter. The Prosecutor General of the Nation approves the adoption based on the Law Regulating Notarial Processing of Matters Falling Under Voluntary Jurisdiction, without considering the best interests of the child [This constitutes a violation of LPINA and the Convention on the Rights of the Child]. This fact, together with the international demand for children, has given rise to networks that engage in the supply of girls and boys for adoption for commercial purposes. Adoptions are a source of funds for countless people from all walks of life, different professions and every part of the country, including outside the national borders. For those who take part in this criminal organization, adoptions are a source of profits. These networks buy babies from fathers, mothers and birth families, manipulating their needs and their poverty, and also engineer the kidnapping and disappearance of girls and boys for the purpose of giving them up for adoption. If one looks for cases and statistics that corroborate the existence of a market for Guatemalan girls and boys for international adoption, the answers are fourfold: the illegality of adoption procedures, the demand for babies among foreign families, the operations of adoption networks and child trafficking. 23 adoptions in guatemala - protection or business? 1. International Adoptions Girls and boys given up for adoption during different periods and years (1980 – 2007) Stated in absolute values and non-continuous periods GRÁFICA 1 6,000 5,577 4,918 5,000 3,833 4,000 4,048 3,289 3,000 2,320 2,000 1,265 1,370 2,322 3,494 2,139 2,271 1,636 731 1,000 Proy agosto Enero a 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 los 80 Década de 0 2007 2007 500 Source: based on statistics of the National Commission for the Search for Disappeared Children, 2003; and the Prosecutor General of the Nation, 2007. Guatemala. Although there were adoption procedures prior to 1996, precise records started to be kept regarding their increase after that year. The National Commission for the Search for Disappeared Children had a total of 500 cases of girls and boys given up for adoption illegally during the internal armed conflict and 584 disappeared children have not been located. This is not the total figure on the number of girls and boys in an irregular situation during that period, since it is estimated that there were more than 5,000 children who disappeared and were unprotected. 24 According to statistics of the Office of the Prosecutor General of the Nation, adoptions increased 6.7 times during the eleven-year period 1996-2006. In other words, from 731 adoptions in 1996 the number rose to 4,918 in 2006, or a difference in absolute values of 4,187. From 1996 to 2002 there was a consistent increase, but in 2003 there was a 35% reduction. This reduction is due to two factors: one, the international situation concerning the implementation of the Hague Convention by the Guatemalan State and that six countries decided to refuse to adopt Guatemalan girls and boys because they felt that adoption procedures were irregular and connected to child trafficking; and two, that the Prosecutor General did not approve adoptions from May to September 2003, because the Court of Constitutionality had not made a ruling on the “amparo” appeal based on the unconstitutionality of the Convention. Countries where Guatemalan girls and boys have been adopted Years1997 a 2007 Stated in absolute values for non-consecutive periods CUADRO 1 COUNTRY 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 TOTAL 2007 SUBTOTAL TOTAL 1,265 1,370 1,636 2,320 2,322 3,289 2,139 3,833 4,048 4,918 27,140 3,494 30,634 UNITED STATES 831 854 1,060 1,612 1,829 2,843 1,823 3,572 3,864 4,757 23,045 3,238 26,283 FRANCE 163 166 192 238 189 233 199 50 5 0 1,435 0 1,435 0 23 75 105 76 62 51 108 76 81 657 185 842 SPAIN 51 71 75 94 34 27 10 1 4 6 373 5 378 CANADA 67 73 70 67 19 13 0 0 5 0 314 1 315 ITALY 43 32 17 28 15 20 8 14 17 9 203 3 206 5 19 40 53 49 1 1 5 2 2 177 0 177 IRELAND 21 17 15 22 16 15 10 13 10 6 145 11 156 ISRAEL 24 31 5 4 11 6 0 4 20 17 122 17 139 GERMANY 3 13 27 14 24 10 1 9 2 1 104 0 104 UNITED KINGDOM 20 23 19 9 3 6 1 0 3 24 108 23 131 BELGIUM 8 8 8 7 6 5 1 14 8 4 69 0 69 SWITZERLAND 6 8 10 15 13 8 1 4 0 0 65 3 68 ENGLAND 0 4 4 7 8 4 10 12 7 0 56 0 56 LUXEMBOURG 8 3 3 14 12 6 1 0 0 0 47 0 47 GREAT BRITAIN 0 0 0 0 0 15 0 15 7 0 37 0 37 NORWAY 4 6 8 6 2 5 1 1 0 0 33 0 33 AUSTRIA 1 1 1 5 4 2 5 4 4 3 30 0 30 DENMARK 3 5 2 2 4 1 2 1 4 0 24 0 24 AUSTRALIA 2 5 0 9 0 2 0 3 1 1 23 0 23 SWEDEN 3 7 2 2 7 0 0 0 0 0 21 0 21 BAHAMAS 0 1 0 2 0 1 9 0 0 0 13 0 13 MEXICO 1 0 1 2 0 2 0 1 0 2 9 0 9 AFRICA 0 0 1 0 1 0 2 1 0 0 5 2 7 FINLAND 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 4 0 4 COLOMBIA 0 0 0 2 0 0 1 0 0 0 3 0 3 PUERTO RICO 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 3 0 3 EGYPT 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 HONDURAS 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 2 3 CHILE 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 2 COSTA RICA 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 ECUADOR 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 HUNGARY 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 GIBRALTAR 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 PERU 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 ARGENTINA 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 ARAB EMIRATES 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 ESTONIA 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 BERMUDAS 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 CHINA 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 CYPRUS 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 PORTUGAL 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 GUATEMALA HOLLAND Source: Based on statistics of the Office of the Prosecutor General of the Nation. Guatemala, 2007. By 2004 they had increased 1.8 times, due to the decision by the Court of Constitutionality to declare that the accession process by Guatemala to the Hague Convention is unconstitutional, thus allowing lawyers and notaries public to carry out adoption proceedings directly without a judicial decision on the matter. The authorities of the Office of the Prosecutor General of the Nation changed that year, which might have had an influence if there had been a willingness to authorize adoptions without a systematic investigation of each case. 25