V P S

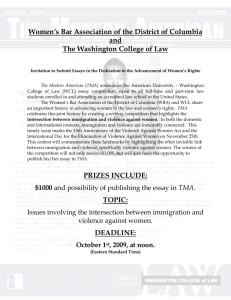

advertisement