“A Nightmare on the Minds of the Living:” the

advertisement

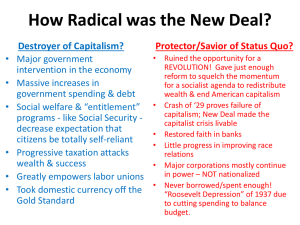

Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 “A Nightmare on the Minds of the Living:” Capitalism is Still the Keyword in Cultural Studies By Billy Williams Abstract: In this article, I survey the uses of the keyword “capitalism” in a selection of critical readings from topics within Cultural Studies. Even though Marx’s social theory has been complicated by structuralist and post-structuralist questions, the formative problematic of Cultural Studies emerged in early twentieth-century Marxian critiques of bourgeois ideology. The term, therefore, remains integral to the various threads of inquiry: Critical Race Theory, Postcolonial Studies, Nation-based Critiques, and Transnational and Ethnic Studies. Despite attacks on the very subjectivity and nomological laws that Marx assumed, positioning of identity within contemporary normative structures still requires an account of the subject’s relation to the modes of material production. Cultural production, like material production, is more fluid now than ever in human history. The critics - from Fanon to Anzaldúa - through which I chase the keyword “capitalism” represent the canon [at least the comps reading list] of Cultural Studies, and they use the evolving meaning of the term—from technical to critical—to excavate the reciprocal processes of culture, ideology, and identity formations, to pull the curtain away from what Marx called “this process of worldhistorical necromancy.” Billy Williams is in his second year of coursework toward a PhD in Cultural Studies, where he divides his energies between early modern consciousness and ideology and contemporary formation of private/public. He has a Masters of Arts in English from the University of Arkansas, teaches literature at a prep school in Pasadena, and lives near Griffith Park in Los Angeles. He loves Leoncavallo, Steve Earle, and Prince. culture critique, the online journal of the cultural studies program at CGU, situates culture as a terrain of political and economic struggle. The journal emphasizes the ideological dimension of cultural practices and politics, as well as their radical potential in subverting the mechanisms of power and money that colonize the life-world. http://ccjournal.cgu.edu © 2011 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 INTRODUCTION--From technical to critical term Though the term has come to dominate political and cultural discussion in the last century and a half, the first uses of the word “capital” in the English language were mundane and technical, referring to the “original funds of a trader, company, or corporation.” i The etymology of the word, coming from “caput,” meaning “head,” suggests that these original funds were disposed by a sovereign to an individual “capitalist,” or “one who has capital available for employment in financial or industrial enterprises;” ii in other words, the propriety over excess surplus-value was granted by the king. Raymond Williams explains that the words “capital” and “capitalist” were general terms in “any economic system;” however, by the nineteenth century, the “uses…moved towards specific functions in a particular stage of historical development; it is this use that crystallized in capitalism.” iii Of course, “capitalism” is not commonly used by economists today, who “take as their object a system that is variously referred to as the ‘market economy’…a ‘mixed economy’…or just ‘the economy’.” iv Instead, since the mid-nineteenth century, capitalism has become a critical term for the historical rise of the bourgeois economic class as demonstrated by social theorists, particularly Marx and Engels. Historically, capitalism is a mode of material production "based on private ownership of the major means of production and subsistence (implements, land, food) by capitalists" who "use part of their capital to buy labor power of another social class, the proletariat.” v Marxian criticism of capitalism includes a critique of the ideological "superstructure" by arguing "that all social and political forms, and all major historical change, are ultimately determined by conflicts within material production.” vi Therefore, as its technical meaning has declined from mainstream economics, its critical use has expanded its meaning: "The 1 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 keyword 'capitalism' thus designates not just an economic structure, but also the conflicts and contradictions inherent in that structure.” vii The term capitalism comes laden with syncretic critical values that reach into everything from rheology (or the science of the deformation and flow of matter), ideology, politics, epistemology, and ontology. THE DANGER OF TELEOLOGICAL DETERMINISM--Hermeneutic and Nomological Application Drawn from Hegelian dialectical idealism, Marx's theory of history seems to suggest an a priori ideal toward which all human development strives. Fredric Jameson points out the danger of this view, which "still raises some embarrassing questions...with the result that, even if before there were histories--many of them, and unrelated--now there is tendentially only one, on an ever more homogeneous horizon, as far as the eye can see.” viii A belief that Marxian criticism is another nomological science (a science which establishes "natural" laws) of the European Enlightenment program suggests that postcolonial nationalist and economic development must naturally follow European metropolitan models, a determinist view of history too conservative of the "myth of Western exceptionalism.” ix Instead, Jameson offers "a careful reading of the Manifesto" that describes capitalism as an "extraordinarily complex and temporally distended and developed laboratory...seen as a process rather than a stage in its own right.” x Marx himself, in fact, denied determinist historiography. Terry Eagleton quotes Marx from The Holy Family: "History does nothing...'history' is not a person apart, using man as a means for its own particular ends; history is nothing but the activity of man pursuing his aim.” xi Therefore, recent theorists have emphasized Marxism's hermeneutic qualities to avoid "certain concepts from the left...in particular, a teleological conception of economic 2 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 history in terms of a linear progression of modes of production.” xii Using the longue duree of Braudelian historiography, Immanuel Wallerstein, for example, explains how since the sixteenth century the "world system...is and has always been a world-economy" and that it "is and always has been a capitalist world economy.” xiii He provides, therefore, an interpretation of an historical period characterized by a "core-periphery axis of the division of labor" xiv without placing it in the context of a linear progression of development. Marxist criticism of capitalism as a hermeneutic tool will be particularly important in our discussion below of Benedict Anderson’s explanation of nationalization and Frantz Fanon’s goal of inventing “a new man in full, something which Europe has been incapable of achieving.” xv WHAT HAS ALL THIS TO DO WITH CULTURAL STUDIES? We are defining "culture" here as "the production and circulation of sense, meaning, and consciousness.” xvi Culture is both “material production” and “signifying or symbolic systems.” xvii In the sections below, we are tracing the authors' applications of the critical term capitalism to various approaches of understanding how culture relates to identity, empowerment, and political liberty. The production and distribution of surplus value and the maintenance of ideology, matters at the core of capitalism, are integral to these problems, as Rousseau points out in Discourse on the Origin of Inequality: "The cultivation of the earth necessarily brought about its distribution; and property, once recognised, gave rise to the first rules of justice; for to secure each man his own, it had to be possible for each to have something." xviii 3 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 Rousseau goes on to claim that "the right of property...is different from the right deducible from the law of nature.” xix Therefore, property is a human creation, historical and contingent, that lead human beings to "come to love authority more than independence, and submit to slavery, that they may in turn enslave others.” xx Historical objectification and dispossession seem to run through the epistemic and concrete forms of violence investigated by Critical Race Theory, Postcolonial Studies, Nation-Based Approaches, and Transnational and Ethnic Studies. Because of the ubiquity of the capitalist mode of production, these critics must engage capitalism as a critical tool to understand forms of culture. CRITICAL RACE THEORY In determining the extent to which race influences identity formation and access to culture, we must consider whether African slavery was originally a race-based system or labor-based system. Which comes first, in other words, race or economic class in a capitalist system? Eric Williams suggests that the African slave-trade was "only a solution, in certain historical circumstances, of the Caribbean labor problem.” xxi Capitalism required slavery as a system of labor supply more efficient than white indentured servitude. Capitalism, as a system, has no values greater than the production of increasing capital; “Capital thirsts for surplus value because surplus value is the only ultimate source of profits and therefore of additional capital.” xxii Williams explains that mercantilist capitalism made slavery possible, which in turn made industrial capitalism and the growth of cities such as Liverpool and Manchester possible. The growth of industrial capitalism, though, “turned round and destroyed the power of commercial capitalism, slavery, and all its works.” xxiii Rather than the benevolence of the 4 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 abolitionists - many of whom, Williams points out, had already profited from slavery “Commerce was the great emancipator.” xxiv The concomitant racism, then, is an attempt to naturalize the economic inequality, a product of slavery rather than one of its causes. Though Frantz Fanon's Black Skin, White Masks lacks the explicit critique of capitalism in his Wretched of the Earth, he does point out the European epistemology that imagines the world as object: "The white man wants the world; he wants it for himself...He enslaves it. His relationship with the world is one of appropriation.” xxv Black slavery, then, is another manifestation of "the right of property, which is different from the right deducible from the law of nature.” xxvi This epistemology results in psychological violence. “Inferiorization,” he writes, ‘is the native correlative to the European’s feeling of superiority.” xxvii Racial inferiorization, he goes on to suggest, is correlative to economic inferiorization, as he quotes the poet Jacques Roumain: “I want to be of your race alone/Workers peasants of every land…/…white worker in Detroit black peon in Alabama/Countless people in capitalist slavery/Destiny ranges us shoulder to shoulder.” xxviii In The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon explains that, originally, capitalism required colonies to expand supplies of raw resources, including labor; then, post-colonial capitalism converted the colonized to expanding commercial markets. Regardless of the stage of expansion, though, capitalism uses racial inferiority to rationalize economic inferiority. “Destiny ranges” the proletariat of every race “shoulder to shoulder.” Likewise, Omi and Winant place capitalism high among the factors involved in "The Evolution of Modern Racial Awareness:" "The European explorers were the advanced guard of merchant capitalism, which sought new openings for trade.” xxix They start their 5 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 article, though, criticizing the failure of the "towering figures" of 19th-century social theorists who, in their analysis of "the transition from feudalism to capitalism," predicted that "social distinctions such as race and ethnicity would decrease in importance" as "society split up into two great, antagonistic classes.” xxx W.E.B. Du Bois, writing much earlier than Fanon, Cesaire, Omi, and Winant, seems optimistic about early examples of this conversion of enslaved labor into free-market labor: "Such contributions [to educational institutions], together with the buying of land and various other enterprises, showed that the ex-slave was handling some free capital already.” xxxi However, Brantlinger offers an explanation of the lagging advancement of black bourgeois aspirations, explaining that in Victorian literature, the idea that "Africans were suited only for manual labor" was often repeated. He offers, for example, Henry Merriman's novel With Edged Tools which "implies that Africans are not suited for freedom.” xxxii Presumably, then, as constructed in the 1890s English imagination, Africans were the prototypical laboring class, their labor their only capital. The deleterious consequences of this rationalized prejudice plagues economic development of racial minorities nearly a century and a half after the end of slavery. POSTCOLONIAL STUDIES An important question in the critique of European colonialism is whether colonialism was simply a "phase" of global capitalism, a world-system that survived colonial administration of "native economies" to take the form of financial imperialism? Aime Cesaire, in Discourse on Colonialism, takes only eighty-seven words to invoke capitalism's involvement in colonialism, naming "the problem of the proletariat and the colonial problem" as the two major problems that "two centuries of bourgeois rule" has 6 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 created. xxxiii Native economies, he argues in words that echo Rousseau, were "natural economies," and "not only ante-capitalist...but also anti-capitalist." They were "cooperative societies, fraternal societies...destroyed by imperialism." Instead of "contact," colonialism established "relations of domination and submission which turned...the indigenous man into an instrument of production.” xxxiv Cesaire, therefore, emphasizes the material violence of colonialism. Likewise, though Edward Said does not focus on capitalism specifically, he does claim, in the “Introduction” to Orientalism, that Westerners "dominate" Orientals, "which usually means having their land occupied, their internal affairs rigidly controlled, their blood and treasure put at the disposal of one or another Western power.” xxxv Cesaire includes a long list of these dominating enemies, "all of them tools," he writes, "of capitalism" and thus "all henceforth answerable for the violence of the revolutionary action.” xxxvi He also warns of a continued imperialism in the form of "the modern barbarian," American high finance, which, he claims, "considers that the time has come to raid every colony in the world.” xxxvii Capitalism, born in the womb of British slave trading, and reared on the blood of European colonial labor, has grown into "American domination--the only domination from which one never recovers...unscarred.” xxxviii Like Cesaire, Frantz Fanon sees European colonialism as a phase of capitalist expansion, writing in The Wretched of the Earth, "Capitalism, in its expansionist phase, regarded the colonies as a source of raw materials which once processed could be unloaded on the European market. After a phase of capital accumulation, capitalism has now modified its notion of profitability. The colonies have become a market. The colonial population is a consumer market.” xxxix Unlike Cesaire, though, Fanon is hopeful 7 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 that the post-colonial consciousness will lead to internationalism. African nationalism, he writes, "if it expresses the manifest will of the people...will necessarily lead to the discovery and advancement of universalizing values." Liberated from mere production and consumption, "international consciousness establishes itself and thrives...at the heart of national consciousness.” xl Because they thought they were "part of the prodigious adventure of the European Spirit," the European proletariat never responded to "the call [to join together as an international class].” xli Post-colonial nations "must be pioneers...for ourselves and for humanity" and "develop a new way of thinking, and endeavor to create a new man" that does not see the world merely as objective commodity, property for exploitation. xlii By emphasizing the material violence of colonialism, Fanon rejects the idea that former colonies must follow the development models of European metropoles. Not all of our critics focus on the material violence of colonialism. In "Can the Subaltern Speak," Gayatri Spivak questions the Western critique of capitalism, particularly Marx's distinction between representation in the political context, Vertretung, and representation in the economic context, Darstellung, to argue that "Western intellectual production is, in many ways, complicit with Western international economic interests.” xliii Ironically using a Derridean re-reading of Marx against European Marxists, Spivak shows how Western intellectuals have ignored the "epistemic violence" colonialism visited upon colonial subjectivity; however, Benita Parry, in "Problems in Current Theories of Colonial Discourse," complains that because Spivak rejects Western historiography without producing her "own account of change, discontinuity, differential periods and particular social conflicts," she reduces all "imperialism," which includes 8 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 post-colonial "international finance capitalism," to "colonialism.” xliv Parry prefers the dialectical criticism of Cesaire and Fanon who seem to remember that “the need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the whole surface of the globe.” xlv In other words, active colonialism was a specific form of a more general and insidious imperialism that preceded and survives the metropolitan administration of the colonies, an imperialism intent on continued material violence. NATION-BASED APPROACHES Closely related to the concerns of post-colonial questions are those asked by critics of the modern nation-state. Benedict Anderson tries to answer the question of why nations have not dissolved into internationalist economic classes in a classical Marxist description of historical progress. In Imagined Communities, he claims that among the factors leading to the popularity of the nation as a "horizontal-secular, transverse-time" community, "a strong case can be made for the primacy of capitalism.” xlvi In the first wave of nationalism, print-capitalism created monoglot mass reading publics/markets and established state-administrative languages in metropolitan centers in Europe. Creole homines novi developed colonial nations following metropolitan models, and finally, in the "last wave of nationalism," former Asian and African colonies became nations "in response to the new-style global imperialism made possible by the achievements of industrial capitalism.” xlvii Psychologically, the "imagined community" of the nation answers the question, "why are we all here together?" Materially, it provides an administration of resource distribution, an "aggregation of bodies" with pooled economic interests. Instead of a “natural” system of organization, “the executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.” xlviii 9 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 In Keywords for American Studies, Weinbaum cites Wallerstein in support of this view of nations, claiming that they "can be regarded as racialized economic and political units that compete within a world marketplace comprised of similar units. As the globe divided into core and periphery...nations at the core often rationalized their economic exploitation of those of the periphery by racializing it.” xlix The strength of the state in the capitalist world-system determines the levels of wealth that can be accumulated; “the weaker the state, the less wealth can be accumulated through economically productive activities.” l Because the myth of the nation reinforces the authority of the state, “we should think of the ‘nation-state’ as the asymptote toward which all states aspire.” li Anderson seeks to place the foundation of the mythic structures of nations squarely in the development of bourgeois society. In seeking to explain the nation myth as narration, Homi Bhabha invokes Fanon's "internationalism," claiming, "It is this international dimension both within the margins of the nation-space and in the boundaries in-between nations and peoples that the authors of [Nation and Narration] have sought to represent in their essays.” lii Perhaps what Bhabha is seeing in the “margins of the nation-space” is what has not occurred within the nation-space, particularly Marx’s assertion in the Manifesto that “the struggle of the proletariat with the bourgeoisie is at first a national struggle.” liii As Fanon pointed out above, the proletariat of the metropolitan nations has not answered the call, perhaps because, as Anderson points out, the nation does not dissolve easily, precisely because it is not real. In "The National Longing for Form," Brennan explains how the nation-state becomes a kind of secular myth, taking over "religion's social role.” liv Like Anderson, Brennan places the novel and the newspaper, both products of bourgeois society, as the 10 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 myth-building forms for the modern nation. Despite Renan’s confidence that “we have driven metaphysical and theological abstractions out of politics,” lv the modern nation state remains the “illusory sun which revolves around man so long as he does not revolve around himself.” lvi Global capitalism maintains the myth of nation state to undermine internationalist economic solidarities. TRANSNATIONAL AND ETHNIC STUDIES Homi Bhabha’s invocation of the liminal spaces, the aporia between states, introduces the transnational question of whether political boundaries are the telos of historical development or merely abstract attempts to administrate flows of concrete material resources. James Clifford claims anthropologists "are in a much better position, now, to contribute to a genuinely comparative, and non-teleological, cultural studies, a field no longer limited to 'advanced,' 'late capitalist' societies.” lvii Two examples he offers of this position are: first, "a comprehensive theory of migration and capitalist labor regimes" proposed by Robin Cohen's The New Helots: Migrants in the International Division of Labor; and second, Orlando Patterson's "The Emerging West Atlantic System," which illustrates "the growing transnational character of capitalism, its need to organize markets at a regional level.” lviii An anthropology based on the fixed field model has little value in a world system in which populations, reduced to the commodity of labor power, flows as freely as every other form of capital. Paul Gilroy claims his project in The Black Atlantic converges with Marxism, especially in their shared optimism in the possibility of "Reason [being] thus reunited with the happiness and freedom of individuals and the reign of justice within the collectivity;” lix however, where Marxism focuses on "systemic crisis," he focuses on the 11 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 "lived crisis" of the memory of slavery, which "whether it encapsulates the inner essence of capitalism or was a vestigial, essentially precapitalist element in a dependent relationship to capitalism proper, it provided the foundations for a distinctive network of economic, social, and political relations" and "has retained a central place in the historical memories of the black Atlantic.” lx On the other hand, transnational capitalism is much more important to the analysis of Aihwa Ong, who claims, "An understanding of political economy remains central as capitalism - in the sense of production systems, capital accumulation, financial markets, the extraction of surplus value, and economic booms and crises - has become even more deeply embroiled in the ways different cultural logics give meaning to our dreams, actions, goals, and sense of how we are to conduct ourselves in the world.” lxi Ong reverses the method of Gilroy; instead of moving from lived cultural experience to a theory of consciousness, she investigates the "cultural specificities of how capitalism operates among 'Chinese' fraternal networks and publics across the Asia Pacific region.” lxii Both Gilroy and Ong, though, recognize the dilating perforations in national boundaries, apertures through which cultural production necessarily follows capital. Nowhere is the impact of the border more eloquently interrogated than in Gloria Anzaldúa's Borderlands/La Frontera, though she does not concentrate on the term capitalism, she does describe the impact of global capitalism on the land and the people who live there. "In the 1950s,” she writes, “I saw the land, cut up into thousands of neat rectangles and squares.” lxiii The dispossession of the Indian lands had begun in the nineteenth century, with the collusion of "powerful landowners in Mexico" and "U.S. colonizing companies," and continues today: "Currently, Mexico and her eighty million 12 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 citizens are almost completely dependent on the U.S. market.” lxiv Her description of the maquiladoras and her imagery of a laborer in "A Sea of Cabbages" – “Man in a green sea./His inheritance: thick stained hand/rooting in the earth" lxv – recall Rousseau's warning: "from the moment one man began to stand in need of the help of another; from the moment it appeared advantageous to any one man to have enough provisions for two, equality disappeared, property was introduced, work became indispensible, and vast forests became smiling fields, which man had to water with the sweat of his brow, and where slavery and misery were soon seen to germinate and grow up with the crops." lxvi Though the field in which he works is thousands of miles and years distant from the world of Franz Fanon, this cabbage picker stands “shoulder to shoulder” with the peasants of the world, and reminds us that “if working conditions are not modified it will take centuries to humanize this world which the imperialist forces have reduced to the animal level.” lxvii Anzaldúa’s poetry humanizes this worker, and the alternative that Fanon believed in but never fully explained might be found in Anzaldúa's hyphenated term nos-otras, in which self and other, owner and owned, become one. CONCLUSIONS In King Lear, Shakespeare’s titular sovereign, exiled within his own realm, realizes: “O, I have ta’en/Too little care of this! Take physic, pomp,/Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,/That thou mayst shake the superflux to them,/and show the heavens more just.” lxviii Here, the term superflux, like capital, implies a historically contingent proprietary agent. The subjects of a sovereign, or “caput,” received surplus-value in 13 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 return for loyalty. Such dependence on a sovereign, Rousseau would claim, emerges as a requirement of property, the primeval inequality: “People have set up chiefs to protect their liberty and not to enslave them.” lxix The critics of the topics above reveal how difficult the identification of the master has become. Ironically, as subjects have become citizens and more empowered politically, the term capital has become naturalized. The conversion of material subsistence into commodity makes private property seem natural. Cheryl Harris refers to this recent tradition of establishing property rights, “the ‘natural’ character of property derivative of custom, contrary to the notion that property is the product of a delegation of sovereign power.” lxx The prodigious applications of the term “capitalism” in these critical texts indicate how deeply the mode of material production affects “the production and circulation of sense, meaning, and consciousness.” Differences among alienated and contentious groups, whether based on racial, ethnic, or national identity, are manifestations of the violence Marx describes in The German Ideology: “as long as a cleavage exists between the particular and the common interest, as long therefore, as activity is not voluntary, but naturally, divided, man’s own deed becomes alien power opposed to him, which enslaves him instead of being controlled by him.” lxxi That “cleavage” leaves spaces for potential or violence. It is the space between subject and object, black and white, the material lacuna in which epistemic violence infests. The gift that Gloria Anzaldúa leaves us, though, she calls a “tolerance of ambiguity” lxxii and describes in the last stanza of her poem, “To live in the Borderlands means you:” To survive the Borderlands you must live sin fronteras be a crossroads. lxxiii 14 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 i Oxford English Dictionary, 1986. Ibid. iii Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society, Rev. ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 51. iv David F. Ruccio, “Capitalism.” Keywords for American Studies, Ed. Bruce Burgett (New York: New York University Press, 2007), 33. v Ernest Mandel, The Place of Marxism in History (Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press, 1994), 1. vi Terry Eagleton, Marx and Freedom (London: Phoenix, 1997), 13. vii Ruccio, 34. viii Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997), 380. ix Ibid., 379. x Ibid., 380. xi Eagleton, 47. xii Manuel De Landa, A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History (New York: Swerve Edition, 2000), 47. xiii Immanuel Wallerstein, World‐Systems Analysis: An Introduction (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004), 23. xiv Ibid., 20. xv Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, Trans. Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 1963), 236. xvi John Hartley, Communication, Cultural, and Media Studies: The Key Concepts, 3rd ed. (London: Routledge, 2002), 51. xvii Raymond Williams, 91. xviii Jean Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on the Origin of Inequality (New York: Classic Books America, 2009), 50. xix Ibid. xx Ibid., 65. xxi Eric Williams, Capitalism and Slavery (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 29. xxii Mandel, 33. xxiii Eric Williams, 210. xxiv Ibid., 172. xxv Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, Trans. Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 1952), 107. xxvi Rousseau, 50. xxvii Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, 73. xxviii Ibid., 114. xxix Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States: from the 1960s to the 1990s (New York: Routledge, 1994), 61. xxx Ibid., 9. xxxi W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folks (New York: Dover, 1994), 20. xxxii Patrick Brantlinger, “Victorians and Africans: The Genealogy of the Myth of the Dark Continent,” Critical Inquiry, no. 12 (1985): 181. xxxiii Aime Cesaire, Discourse on Colonialism, Trans. Joan Pinkham (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000), 31. xxxiv Ibid., 42‐44. xxxv Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), 36. xxxvi Cesaire, 54 ‐55. xxxvii Ibid., 76. xxxviii Ibid., 77. xxxix Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 26. ii 15 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 xl Ibid., 180. Ibid., 237. xlii Ibid., 239. xliii Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak,” The Post‐Colonial Studies Reader, Eds. Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, Helen Tifflin (London: Routledge, 1995), 271. xliv Benita Parry, “Problems in Current Theories of Colonial Discourse,” Oxford Literary Review, no. 9 (1987): 33‐34. xlv Karl Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party, The Portable Marx, Trans. and ed. Eugene Kamenka (New York: Penguin, 1983), 207. xlvi Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Rev. ed. (London: Verso, 2006), 37. xlvii Ibid., 139. xlviii Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party, 206. xlix Alys Eve Weinbaum, “Nation,” Keywords for American Studies, Ed. Bruce Burgett (New York: New York University Press, 2007), 166. l Wallerstein, 53. li Ibid., 54. lii Homi K. Bhabha, “Introduction: narrating the nation,” Nation and Narration, Ed. Homi K. Bhabha (London: Routledge, 1990), 4. liii Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party, 216. liv Timothy Brennan, “The National Longing for Form,” Nation and Narration, Ed. Homi K. Bhabha (London: Routledge, 1990), 59. lv Ernest Renan, “What is a Nation?” Nation and Narration, Ed. Homi K. Bhabha (London: Routledge, 1990), 20. lvi Karl Marx, “Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right,” Early Writings, Trans. and ed. T.B. Bottomore (New York: McGraw‐Hill, 1963), 44. lvii James Clifford, “Traveling Cultures,” Cultural Studies (New York: Routledge, 1992), 104. lviii Ibid., 109. lix Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), 39. lx Ibid., 55. lxi Aihwa Ong, Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logic of Transnationality (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999), 16. lxii Ibid., 17. lxiii Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, 3rd ed. (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1987), 31. lxiv Ibid., 32. lxv Ibid., 154. lxvi Rousseau, 48. lxvii Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 57. lxviii III.iv.32‐36. lxix Rousseau, 58. lxx Cheryl I. Harris, “Whiteness as Property,” Critical Race Theory and Legal Doctrine, 280. lxxi Quoted in Eagleton, 24. lxxii Anzaldúa, 52. lxxiii Ibid., 73. xli 16 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 Bibliography Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Rev. ed. London: Verso, 2006. Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, 3rd ed. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1987. Bhabha, Homi K. “Introduction: narrating the nation,” in Nation and Narration, edited by Homi K. Bhabha, 1-7. London: Routledge, 1990. Brennan, Timothy. “The national longing for form,” in Nation and Narration, edited by Homi K. Bhabha, 44-70. London: Routledge, 1990. Brantlinger, Patrick. “Victorians and Africans: The Genealogy of the Myth of the Dark Continent.” Critical Inquiry 12 (1985): 166-203. Cesaire, Aime. Discourse on Colonialism, translated by Joan Pinkham. New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000. Clifford, James. “Traveling Cultures,” in Cultural Studies, 96-116. New York: Routledge, 1992. De Landa, Manuel. A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History. New York: Swerve Edition, 2000. Du Bois, W.E.B. The Souls of Black Folk. New York: Dover, 1994. Eagleton, Terry. Marx and Freedom. London: Phoenix, 1997. Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks, translated by Richard Philcox. New York: Grove Press, 1952. -----. The Wretched of the Earth, translated by Richard Philcox. New York: Grove Press, 1963. 17 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993. Harris, Cheryl I. “Whiteness as Property,” in Critical Race Theory and Legal Doctrine. 77-92. Hartley, John. Communication, Cultural and Media Studies: The Key Concepts, 3rd ed. London: Routledge, 2002. Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997. Mandel, Ernest. The Place of Marxism in History. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press, 1994. Marx, Karl. “Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right,” in Early Writings, translated and edited by T.B. Bottomore, 41-59. New York: McGrawHill, 1963. -----. Manifesto of the Communist Party, in The Portable Marx, translated and edited by Eugene Kamenka, 203-241. New York: Penguin, 1983. Omi, Michael and Howard Winant. Racial Formation in the United States: from the 1960s to the 1990s. New York: Routledge, 1994. Ong, Aihwa. Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logic of Transnationality. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999. Parry, Benita. “Problems in Current Theories of Colonial Discourse,” Oxford Literary Review 9 (1987): 27-57. Renan, Ernest. “What is a Nation?” in Nation and Narration, edited by Homi K. Bhabha, 8-22. London: Routledge, 1990. 18 Culture Critique March 2011 v 2 No 1 Rousseau, Jean Jacques. Discourse on the Origin of Inequality. New York: Classic Books America, 2009. Ruccio, David F. “Capitalism,” in Keywords for American Studies, edited by Bruce Burgett, 32-36. New York: New York University Press, 2007. Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books, 1979. Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in The Post-Colonial Studies Reader, edited by Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, Helen Tifflin, 271-313. London: Routledge, 1995. Wallerstein, Immanuel. World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004. Weinbaum, Alys Eve. “Nation,” in Keywords for American Studies, edited by Bruce Burgett, 164-170. New York: New York University Press, 2007. Williams, Eric. Capitalism and Slavery. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1994. Williams, Raymond. Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society Rev. ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983. 19