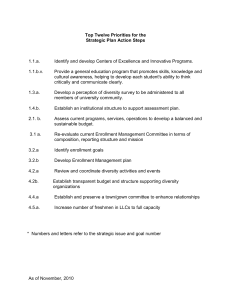

3. S C A : A P

advertisement