Evaluation of the 100,000 Homes Campaign

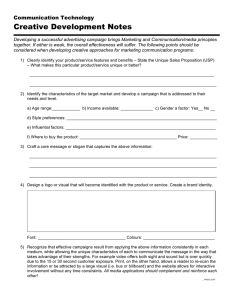

advertisement