U.S. Response to HIV/AIDS in Africa: Bush as a Human... By Alex Hindman and Jean Reith Schroedel

advertisement

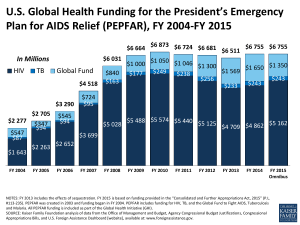

U.S. Response to HIV/AIDS in Africa: Bush as a Human Rights Leader? By Alex Hindman and Jean Reith Schroedel Claremont Graduate University Sub-Saharan Africa continues to face a pandemic of catastrophic proportions. Over 22 million people are infected in the region, almost two-thirds of all infected people globally.1 The United Nations has continued to wrestle with the issue for many years with the establishment of a global fund to address what it calls “a global emergency and one of the most formidable challenges to human life and dignity, as well as to the effective enjoyment of human rights”2 While abatement of HIV/AIDs has been on the policy agenda of many international organizations and governments for years, in the last decade the United States has stepped up its efforts immensely, largely through its international aid program called the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). According the United Nations’ figures, the American contribution to fighting the HIV/AIDS is far larger than any other country.3 Despite the disease continuing to ravage the African continent, PEPFAR’s early successes are showing positive results and are demonstrative of the effect of U.S. leadership in the fight. From a human rights perspective, PEPFAR stands in stark contrast to other less flattering initiatives of President George W. Bush. Rhetorical and actual excesses of the Bush Administration in the prosecution of the “War on Terror” find no shortage of critics in academic 1 “HIV and AIDS in Africa” AVERT.org Accessed at http://www.avert.org/hiv‐aids‐africa.htm on 5 December 2009. United Nations: Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 2 August 2001. Accessed at www.un.org/ga/aids/docs/aress262.pdf on 2 December 2009 . 3 In 2008 the United States government contribution of $4 billion to fighting HIV/AIDS globally constituted more than half of all the funds provided to this effort. The following sources were access on 14 December 2009: www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/Resources/FeatureStories/archive/2009/20090708 kaiser and data.unaids.org/pub/Presentation/2009/20090704 UNAIDS KFF G8 CHARTPACK 2009 en.pdf. 2 2 and journalistic circles. As it relates to human rights, George W. Bush’s record on torture, rendition and indefinite detention at Guantanamo Bay create a picture placing the United States in dubious company on that subject.4 President Bush and a Republican-controlled Congress, which may be accused of transgressing international standards of human rights in Guantanamo, was arguably also largely responsible for saving 1.1 million lives from the scourge of HIV/AIDS in Africa.5 PEPFAR paints a picture of American global leadership that sharply contradicts the popular caricatures of the United States during the Bush years. Explaining this apparent contradiction in the Bush administration’s human rights stance is the focus of this research. We will examine the chronology and policy impetuses for the United States sudden unilateral interest in HIV/AIDS on the African continent. The personal tenacity with which President Bush pursued this global policy issue shows a depth and complexity to his character which scholars have not previously recognized. We seek to find circumstantial conclusions about the moral, religious and human rights motives central to what has been heralded as a 4 For details on the actual practices transgressing human rights during the Bush administration, the best place to start is the U.S. Justice Department memos, available through the New York Times at www.nytimes.com/2009/04/19/opinion/19sun1.html?_r=1&pagewanted=print In its introductory material to these memos, the New York Times has characterized the documents as framed in “the precise bureaucratese favored by dungeon masters throughout history” designed to “provide legal immunity for acts that are clearly illegal, immoral and a violation of this country’s most basic values.” Volumes could be written describing positions of various critics on the human rights record of the Bush Administration. However some additional representative pieces include: Editorial. “Legalizing Torture” The Washington Post 9 June 2004, http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp‐dyn/A26602‐2004Jun8?language=printer. Editorial. “The Price of Our Good Name” New York Times 23 November 2008 http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/23/opinion/23sun1‐ 1.html?pagewanted=print. Editorial. “A Defining Moment for America: The President Goes to Capitol Hill to Lobby for Torture” The Washington Post 15 Sept. 2005. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp‐ dyn/content/article/2006/09/14/AR2006091401587.html. Andrew Sullivan, “Dear President Bush” The Atlantic. October 2009, http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/print/200910/bush‐torture. Amnesty International “United States of America Human rights not hollow words: An appeal to President George W. Bush on his re‐inauguration.” 19 January 2005. http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/AMR51/012/2005. Additionally, see Edward Cody, “China, Others Criticize U.S. Report on Rights” The Washington Post. 4 March 2005. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp‐ dyn/articles/A3840‐2005Mar3.html; Edward M. Gomez “World Views: U.S. Losing Friends Over Torture; Africa’s First Elected Female President” SF Gate 15 Nov. 2005. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi‐ bin/article.cgi?f=/g/a/2005/11/15/worldviews.DTL. 5 Bendavid, Eran, and Jayanta Bhattacharya. 2009. "The President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief in Africa: An Evaluation of Outcomes." Annals of Internal Medicine 150, no. 10: 688‐W:122. 3 policy success.6 Ultimately this particular case is instructive of a more general point, namely that a U.S. President’s can focus attention on an issue, build bipartisan coalitions and ultimately pass a legislative initiative that is unlikely to provide electoral benefits to either himself or members of Congress. Chronology of the Legislation The United States Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria Act of 2003 (P.L. 108-25) established the legislative basis for PEPFAR.7 Specifically, the Congress authorized appropriations totaling $15 billion over 5 years to help stem the spread of the disease in 14 Focus Countries, 12 of which are in Sub-Saharan Africa.8 PEPFAR utilizes the ABC model9 and attempted to tailor nation specific plans using a variety of prevention and treatment methods. One central method of treatment involved the United States providing antiretroviral drugs to impoverished HIV/AIDS victims in the Focus Countries. What made the entire process possible was the U.S. willingness to purchase generic antiretroviral drugs at a cost-feasible level. Structurally, within the U.S. Government the legislation established the Office of the Global Aids Coordinator (OGAC), within the U.S. State Department, occupied by an ambassador 6 Kellie Moss, “PEPFAR Reauthorization: Key Policy Debates and Changes to U.S. International HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Programs and Funding.” Congressional Research Service: CRS Report for Congress. 29 January 2009. Accessed at http://assets.opencrs.com/rpts/RL34569_20090129.pdf/ on 5 December 2009. 7 President’s Plan for Emergency AIDS Relief, “About PEPFAR” Accessed at http://www.pepfar.gov/about/index.htm/ on 5 December 2009. For the text of the legislation, refer to “The United States Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria Act of 2003 (P.L. 108‐25)” at the GPO website. Accessed at http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi‐ bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=108_cong_public_laws&docid=f:publ025.108.pdf on 5 December 2009. 8 Focus Countries included Botswana, Cote d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Guyana, Haiti, Kenya, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. Vietnam was added on June 23, 2004, bringing the total to 15 Focus Countries. See “The U.S. President’s Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)” Accessed at http://www.avert.org/pepfar.htm on 5 December 2009. 9 The ABC model for HIV/AIDS prevention is based on a successful program developed in Uganda. The ABC of the model stands for abstinence, being faithful and condom use. 4 ranked official to administer the program. The Leadership Act also authorized the United States to spend $1 billion to fulfill the U.S. commitment to the UN Global AIDS fund.10 Jay Lefkowitz, a former Bush staffer with an intimate view of the early policy development within the Executive Branch, provides an early description of the policy debates which occurred behind close-doors from the earliest days of Bush’s tenure. Lefkowitz outlines a careful progression starting, from his vantage point, in March of 2001 when the Bush administration established a cabinet-level task force for the specific purpose of addressing AIDS globally. Secretary of State Colin Powell and Secretary of Health and Human Services Tommy Thompson provided the titular leadership on the issue despite the fact that much of the deliberations over the direction of the initiative remained within the White House. 11 For roughly the next year, the Bush White House internally developed a structured plan to address the HIV/AIDS crisis abroad. The President’s staff, and the President remained committed to addressing the disease while many in his administration remained consumed with addressing the 9/11 attacks. With the President’s likely insistence, realigning America’s efforts to address the global HIV/AIDS epidemic remained actively on the agenda of Lefkowitz and his small working group.12 First unveiled in President Bush’s 2003 State of the Union Address, 10 See “The United States Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria Act of 2003 (P.L. 108‐25)” supra., at Sec. 202. 11 Jay Lefkowitz. “AIDS and the President—An Inside Account” Commentary January 2009. Accessed at http://www.commentarymagazine.com/viewarticle.cfm/aids‐and‐the‐president‐‐an‐inside‐account‐14057/ on 5 December 2009. Hereafter referred to as “Lefkowitz, supra.” 12 Lefkowitz, supra. One important note to consider is the diverse group of individuals which Bush brought together to work on this project internally. While Lefkowitz was Deputy Domestic Policy Advisor, he was joined as his article indicates by Dr. Anthony Fauci, a leading AIDS researcher with the National Institutes of Health (NIH); Gary Edson, Deputy National Security Advisor; Kristen Silverberg, at the time Special Assistant to the President and later Ambassador to the European Union. As discussions advanced this internal White House task force was expanded to include more government officials and consulted with a variety of outside groups and experts. While Lefkowitz does not provide a complete list, he notes that this was far from a “Republicans‐only” group. Dr. Joseph O’Neill, a Clinton‐era holdover and AIDS physician, in the Department of Health and Human Services was brought on in late July 2002. The future Global AIDS coordinator Ambassador Mark Dybul was brought on about the same 5 PEPFAR was immediately picked up by several members of Congress. Both Republican and Democratic legislators provided critical leadership in pushing forward the legislation. Representative Henry Hyde (R-IL) and Representative Tom Lantos (D-CA)13 jointly brought the legislation first to the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives. On the Senate side, the legislation was shepherded by Senator Richard Lugar (R-IN) and the Majority Leader, Senator Bill Frist (R-TN). Strategically, the White House had decided to have their allies introduce the bill in the House first rather than have the bill mangled in the U.S. Senate by traditional prerogatives and procedures of formidable Senators.14 Representatives Hyde and Lantos, from their positions as Chair and Ranking Member respectively on the House Foreign Relations committee were both actively interested in human rights issues. These men, a Republican and a Democrat respectively pushed the bill through their committee reporting it out to the full body on April 2, 2003. When the bill was reported from the House International Relations Committee by a strong favorable vote of 37-8, the prospect of its passage became more apparent to all involved.15 Some liberal Democrats wanted to see the money increased and given as a larger contribution to time to assist in the development of the program. Ambassador Dybul was then serving as a staffer to Dr. Fauci at NIH. Robin Cleveland from the Office of Management and Budget was also added late in 2002 to determine the financial feasibility of the program. As is the norm with these types of government task forces membership changes from time to time as different portions of plans are addressed while a core group remains focused on the overall plan and resulting legislative process. 13 Throughout his political career, Representative Tom Lantos, who died in 2008, was a leading human rights advocate within Congress. Much of his activism on these issues was rooted in his experiences as a Holocaust survivor in his native Hungary. 14 Traditions and rules of the United States Senate allow individual Senators to place holds on legislation, prolong debate and slow down the policy process. For more on Senate procedure, refer to Walter Oleszek Congressional Procedure and the Policy Process. 7th ed. (Washington: CQ Press, 2007). It was, in part, to avoid these difficulties that the Bush White House chose to bring their initiative to the House first. 15 See House Report 108‐060. Available through the GPO at http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi‐ bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=108_cong_reports&docid=f:hr060.108.pdf. Accessed on 5 December 2009. 6 the UN Global Fund, but that would have undercut support among conservative Republicans.16 Opposition to the committee bill came from the political right on moral grounds that U.S. taxpayers should not be funding contraceptives with which many Americans have religious/ideological objections. Also, skepticism over the role of the United Nations and lack of accountability both influenced conservatives for support for the U.S. centeredness of the PEPFAR’s initiative.17 Clearly, while agreeing in the abstract that the United States should do more to abate HIV/AIDS in Africa, the means to achieve this outcome was proving controversial and firm leadership from the White House saw the process through. After it was voted out of committee, the President actively pushed his initiative devoting time to persuade them both publically and privately.18 On April 29, 2003, the President 16 Liberals were opposed to efforts to strip condom funding from the bill, as well as efforts to remove authorization for funding the UN Global Fund. They were “prepared to fight for an earmark of $200 million,” but with support of some conservatives were able to ensure authorization of $1 billion in the final bill. While the bill authorized $1 billion, the administration signaled to Democrats that it only intended to fund $200 million. This signal may have been a cue to Congressional Democrats to realistically limit their expectations. (see Niels C. Sorrells, “House Passes Bush Anti‐AIDS Plan; Democrats Challenge GOP Changes” CQ Weekly. 3 May 2003. pg. 1056.) 17 One illustrative amendment attempted to redress issues many conservatives had with condom usage as a viable method of prevention. The Pitts Amendment, sponsored by Representative Joseph Pitts (R‐PA), was offered to favor abstinence‐only programs for funding over those that favor condom use as a viable prevention method. The amendment was defeated in Committee 20 ayes‐24 opposed, and accepted when reoffered on the floor of the full House by a vote of 220‐197. On this refer to the House Report 108‐060, supra. and “The United States Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria Act of 2003 (P.L. 108‐25)” supra. Despite these political fights, the legislative wording in the final bill encouraged support for abstinence‐only programs, requiring one‐third of the funds appropriated to be used for that purpose. Democrats were heartened that it maintained flexibility for country specific plans of the OGAC and permitted condoms as possible provisions of those plans. (see Niels C. Sorrells. “House Passes Bush Anti‐AIDS Plan; Democrats Challenge GOP Changes” CQ Weekly. 3 May 2003. pg. 1056). One of Representative Pitts’ staffers is quoted as saying “Congressman Pitts wants to see the Uganda model followed, in that they emphasize abstinence and faithfulness to one’s partner, with condoms in that context.” Similarly Senator Orrin Hatch (R‐UT) a staunch conservative also favors abstinence but notes that condom use “probably has to be part of the plan”. (Both quoted in Jonathan Riehl “Bush Cites Uganda’s Anti‐AIDS Program as Template for Action” CQ Weekly. 8 March 2003. pg 571.) It appears clear that despite conservatives’ objections to condoms they recognized the need for flexibility in responding to the issue. For more on the political divisions among conservatives, see Niels C. Sorrells, “Bright Hopes for AIDS Bill Dim in New Round of Debate” CQ Weekly. 8 March 2003. pg 570. 18 See Lefkowitz, supra. He writes, “After a couple weeks of negotiating and redrafting, we had a bill that we thought could pass [from committee]. It was not the bill the President wanted to sign into law, but it was the only one with a chance of getting to the floor of the House, where it could always be improved with amendments.” 7 delivered a speech urging Congress to act and giving political cover to fence-sitting legislators.19 As the strong bipartisan majorities continued to agree on the ends of the legislation, the controversy over the means threatened to derail its passage. Presidential leadership on policy proposals at critical moments is often the difference between success and failure. The PEPFAR initiative was no different. Lefkowitz claims this was strategically expected by the White House, and the bill that had emerged from the House International Relations Committee was a sufficient to get out of committee but deliberately incomplete for that purpose. The President’s allies on the Rules Committee in the House crafted the structure of the floor debate to modify the bill as the White House desired. Despite some religious conservatives’ misgivings with the endorsement of contraceptives, many Republicans came to support the bill despite their individual doubts about the bill.20 Without clear and consistent support from President Bush, many of these members would not have supported the initiative Strong amendment challenges still remained on the House floor when they took up the bill on May 1, 2003. The House considered several amendments to the bill which sought to address a variety of concerns and answer specific issue-based objections some members---and by extension interest groups---had with the legislation. In the end however, the overarching goal of Social liberals (including Republicans) were in abundance on the committee. The President wanted to retain some flexibility for State Department officials, provisions for faith‐based organizations and U.S. control over the programs funds. Had the bill been stopped up in committees or hamstrung by members of both sides of the political spectrum, Lefkowitz writes, that a bill the President cared about very deeply may not have even been considered by the full House. Presidential shepherding of the bill and pressure exerted both publically and privately achieved the result Pres. Bush desired. 19 President George W. Bush “Remarks on the Global HIV/AIDS Initiative” 29 April 2003. Public Papers of the Presidents. 2003. Also available at: John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters, The American Presidency Project [online]. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=431 on 5 December 2009. 20 Representative Henry Hyde (R‐IL) is famously remembered for a 1976 amendment that bears his name. The “Hyde Amendment,” as it is commonly called, prohibits U.S. federal funds from funding abortion. Given conservatives reluctance to fund condoms with tax dollars, Hyde’s support of the bill made passage much more palatable to those who may have misgivings. Perhaps this was part of the White House strategy, namely if a leading social conservative such as Hyde was in front of this bill, other social conservatives would find it acceptable to join him. 8 meeting the President’s charge to do more carried the day. Some House amendments, which would have hamstrung the flexibility of the Office of Global AIDS Coordinator to develop nation-specific plans to treat and prevent the disease, were defeated. The White House also utilized this process as well carefully deciding which adjustments it wanted to make to the bill before final passage. The House passed the bill the first time by a recorded vote of 375-41.21 Sending the bill to the Senate, it received another challenge from Senators who attempted to insert amendments which reflected many of the issues of concern to members of the House. Senator Richard Durbin introduced an amendment which would have authorized an appropriation of $500 million dollars to be contributed to the UN Global Fund without conditions.22 Additionally, Senator Diane Feinstein (D-CA) attempted to eliminate the abstinence funding requirements within the bill. 23 However, the Senate under the direction of Senator Frist and the Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Senator Richard Lugar (R-IN), they moved the bill through the body unchanged from the version passed by the House. Pushed by a desire to complete the legislation prior to the President’s international summit at the end of May, Senator Frist was able to convince his colleagues that the bill should move through as the House had passed it. The Senate reduced further delay on the bill recognizing as the White House stated on April 29, 2003 that “Time is not on our side” in light of the continuing death in Africa.24 While these life and death considerations were outwardly 21 Sorrells, Niels C. “House Passes Bush Anti‐AIDS Plan; Democrats Challenge GOP Changes” CQ Weekly 3 May 2003. Pg 1056. 22 The purpose of this amendment appears as an attempt to influence the Bush Administration’s commitment to the UN Global Fund and pressure them to increase the signaled amount of $200 million appropriated under the $1 billion authorization. Also it reflects Democrats general favorability for multilateral organizations. 23 Niels C. Sorrells, “Political Expediency Takes Over As Senate Passes AIDS Relief Bill” CQ Weekly 17 May 2003. Pg 1210. The Senate in many ways reflected the debates in the House. Senator Feinstein attempted to remove the Pitts Amendment from the bill and its one‐third funding requirement for the favorability of abstinence‐only programs. (See note 14 above) 24 See Bush, “Remarks on the Global HIV/AIDS Initiative” supra. 9 stated as the reason for the amendment-free passage in the Senate, the promise of Democratic opposition to certain hard-fought provisions in earlier amendment processes may have influenced this strong-armed leadership. The Senate rejected six amendments and passed the bill by voice vote in the early morning hours of May 16, 2003. Partially through a desire to speed the legislation to the President and also to keep Senators focused on the legislation, Senator Frist held the Senate in session until 2am when they finally passed the bill.25 Procedurally then the bill had to return to the House for final passage. Since the bill was unchanged from their initial amendments, the House of Representatives passed the bill by voice vote on May 21, 2003 and sent it to the President for his signature into law. The decision to pass the bill by voice vote is indicative of yet another effort of the White House and Congressional leadership to give cover to members. Without a record of the vote, Members of Congress can avoid accountability on both sides of the issue. The Administration was granted a freer hand perhaps, through a broader legislative mandate to determine the direction of the bill than if recorded votes were required. On May 27, 2003 the President signed the bill which authorized $15 billion funding and establishment of the PEPFAR initiative. 26 25 Democrats promised to push their interests in conference, such as more funding assurances for the UN Global Fund, and less, as then‐Senator Joseph Biden (D‐DE) stated, “moral majority stuff.” see Niels C. Sorrells, “House Passes Bush Anti‐AIDS Plan; Democrats Challenge GOP Changes” CQ Weekly. 3 May 2003. pg 1056.) “Conference Committee” meetings consist of members of both houses of Congress who meet when legislative language on a bill passed by both bodies does not match. Following the conference, the bill is returned to both houses to be passed in total. The White House may have feared that such process and granting Democrats assurances in conference may have jeopardized the entire enterprise as many Republicans could not politically support the provisions Democrats wanted and might have voted against final passage. Avoiding Senate amendments and a necessary conference could have been a deliberate strategic decision on the part of the White House and Senate leadership. 26 See Niels C. Sorrells, “International AIDS Programs Authorized for $15 Billion As Lawmakers Search for Funding” CQ Weekly. 24 May 2003. pg. 1280. Additionally, President George W. Bush “Remarks on Signing the United States Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria Act of 2003.” 27 May 2003. Public Papers of the President, 2003. Also available at: John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters, The American Presidency Project [online]. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=361 on 5 December 2009. 10 The success of the program in its first 4 years led the U.S. Congress to reauthorize the PEPFAR program for an increased amount of $48 billion dollars over the next 4 years through 2013.27 As of September 2008, PEPFAR had supported antiretroviral treatments for 2.1 million people and supportive care for another 10 million people with the disease, 4 million of those “orphaned or vulnerable” children.28 Additionally, the PEPFAR program has increased capacity of Focus Countries to address health care needs. By government estimates, 3.7 million “training and retraining encounters” with in-country health care workers occurred.29 Similarly approximately $734 million was spent between 2004-2008 to develop public/private infrastructure in prevention care and treatment of the disease.30 Nothing sells like success and the reauthorization fight was much less controversial. President Bush signed the PEPFAR reauthorization bill on July 30, 2008.31 The Streams of Influence for this Policy Several convergences occurred early in 2002 that made the passage of significant African HIV/AIDs initiatives possible. Religious and moral appeals were made by President Bush at very key junctures publically and privately which show the deep human rights commitment of the administration in the area of HIV/AIDS abroad. Some commentators have suggested, as this article will address, that there were political motivations for the actions of the administration and 27 Global AIDS Alliance “Fact Sheet: President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)” January 2009. Accessed at http://www.globalaidsalliance.org/info/fact_sheets/ on 5 December 2005. 28 See PEPFAR Report. “Celebrating Life: The U.S. President’s Plan for Emergency AIDS Relief; Fifth Annual Report to Congress” Highlights p. 5‐6. Accessed at http://www.pepfar.gov/press/fifth_annual_report/index.htm on 5 December 2009. 29 Ibid., 7. 30 Ibid., 7. 31 The reauthorization bill was named for the two bipartisan House managers of the bill, Representative Tom Lantos and Representative Henry Hyde both of whom had died in the year preceding the reauthorization for their work on passing the bill. 11 its Congressional allies. However they appear to remain secondary to deeper religious, moral and humanitarian basis for motivating policymakers. While political motives may have played a part, the case remains pretty weak. The White House very easily may have calculated that helping HIV/AIDS victims in Africa softened the President as war leader image. Similarly it is possible that Senator Trent Lott’s (R-AL) racial gaffe in December of 2002 may have impacted the White House’s decision to show a special interest in suffering Africans.32 Such insinuations however appear to be revisionist history. Lefkowitz convincingly writes that the policy was already being developed at a very high level, prior to the September 11th attacks and long before Senator Trent Lott’s comments.33 While it remains impossible to know with certainty the specific motivations of individual actors in this storyline, rhetorical statements indicate significant religious influences, in President Bush’s appeals and some leading Congressional voices. In addition to the President, the careerlong commitments made by various players in key positions over their prior legislative careers influenced the outcome. Senator Bill Frist (R-TN) and Majority Leader of the Senate was a practicing physician prior to his legislative career with an interest in the issue throughout his career.34 Both Senator John Kerry (D-MA), President Bush’s 2004 challenger and Senator 32 John Mercurio “Lott apologizes for Thurmond Comment” 10 Dec 2002. Accessed at http://archives.cnn.com/2002/ALLPOLITICS/12/09/lott.comment/ on 5 December 2009. Senator Lott stated at a birthday party for another Southern Senator, Strom Thurmond, who had previously run as a Segregationist candidate that “I want to say this about my state: When Strom Thurmond ran for president, we voted for him. We're proud of it. And if the rest of the country had followed our lead, we wouldn't have had all these problems over all these years, either.” Critics assailed then Majority Leader Lott for admitting deeply held racist beliefs which remain quite sensitive. Senator Lott was forced to resign his leadership post paving the way for Senator Bill Frist’s rise to the position. 33 Lefkowitz supra. 34 Senator Bill Frist (R‐TN) was well‐known for having gone to Africa to work with HIV/AIDS victims in Africa. He had offered a bill in 2002 on the issue with 2004 Presidential candidate and Senator John Kerry (D‐MA) which passed the Senate but failed to garner support in the House of Representatives. Senator Frist’s commitment to the AIDS issue was well‐established. (See Jonathan Riehl “Bush Proposal to Fight AIDS Assured of Quick Hill Action, Debate Over Funding Level” 1 Feb 2003. pg. 266.) 12 Richard Lugar (R-IN), Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee had an interest in the HIV/AIDS issue. They were drafting related bills at the time the President’s plan was proposed.35 Similarly the two House managers of the bill, Representative Tom Lantos (D-CA) and Representative Henry Hyde (R-IL), were individuals known for their staunch commitment to human rights. The fact that these very important members of Congress played leading roles within their institution is indicative of a deeper commitment among the country’s political elite to combating the global scourge of HIV/AIDS. While some legislators provided support to the initiative from the beginning, others experienced a late-term change of heart. International rock-star turned AIDS activist, Bono, has had a significant influence on the success of the PEPFAR program and anecdotal reports provide insight into the influence he had on the policy in 2003. Lefkowitz mentions that he was shuttled in and out of the White House to consult with the working group, introduce new members and connect the Administration with larger the HIV/AIDS lobby.36 Perhaps most notably in the development of this policy in which Bono had a hand was the conversion of Senator Jesse Helms (R-NC). A social and fiscal conservative, Helms was a frequent target of the American domestic homosexual lobby. He once referred to homosexuals as “weak, morally sick wretches” who were largely responsible for the AIDS epidemic stating, “there is not one single case of AIDS in this country that cannot be traced in origin to sodomy.”37 However accounts claim that Jesse Helms had several meetings with Bono which changed his mind, at least with regard to the 35 Mentioned in Lefkowitz, supra., as the White House tried not to upstage or disrespect the powerful and senior Senator from Indiana who could easily scuttle their HIV/AIDS bill. Senator John Kerry (D‐MA) is mentioned as well as causing some pause among the Bush White House as a formidable foreign policy opinion leader on the issue. 36 Lefkowitz, supra. 37 Quoted in Jake Tapper. “Elizabeth Dole Tries to Rename the AIDS Bill After Jesse Helms” ABC News Political Punch. 16 July 2008. Accessed at http://blogs.abcnews.com/politicalpunch/2008/07/elizabeth‐dole.html. 13 problem of HIV/AIDS in Africa.38 In a speech on March 24, 2002, just one year before PEPFAR passed and while the White House was examining the question, Helms stated: We also have a higher calling, and in the end our conscience is answerable to God. Perhaps, in my eighty-first year, I am too mindful of soon meeting Him, but I know that, like the Samaritan traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho, we cannot turn away when we see our fellow man in need.39 Senator Helms also used the speech to announce his intention to legislatively increase the appropriation U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to fight the HIV/AIDS pandemic by preventing the transmission from pregnant women to their children.40 In 2002, Helms occupied the chair of the Senate Foreign Relations committee prior to his retirement at the end of that year. From this powerful perch, Helms had the ear of the White House as well as significant influence over his colleagues. One such colleague on the committee, Senator Richard Lugar (R-IN) took over the chairmanship after Helms, and presided over Senate deliberations on the Leadership Act. Senator Lugar private cajoling of other Senators was instrumental with Senator Frist in discharging the legislation from the Senate. The venue at which Senator Helms gave his address was the annual convention of Samaritan’s Purse in Washington D.C. Samaritan’s Purse, founded by Franklin Graham, is a 38 Sundaa Bridgett Jones “A Culture Warrior’s Impact on AIDS in Africa” The Root 19 February 2008. Accessed at http://www.theroot.com/views/culture‐warriors‐impact‐aids‐africa 39 Jesse Helms. “We Cannot Turn Away.” Speech. 24 March 2002. Accessed at http://www.jessehelmscenter.org/jessehelms/documents/We_CannotTurn_Away.pdf on 5 December 2009. Ultimately, PEPFAR picked up this Helms program and continued the effort of the mother‐to‐child prevention to great success. 40 “GAA Encouraged by New Proposal for Emergency Funding of Global AIDS” Global AIDS Alliance 25 March 2002 Accessed at http://www.globalaidsalliance.org/newsroom/press_releases/press032502/ on 5 December 2009. The U.S. Agency for International Development is the bureaucratic arm of the U.S. Government responsible for administering foreign aid. 14 philanthropic organization supported by evangelical Christians “providing spiritual and physical aid to hurting people around the world.” Additionally, the charitable, religiously-motivated action is significant as the reason this group is motivated to act starts from an evangelical mission. The group claims: Samaritan's Purse has done our utmost to follow Christ's command by going to the aid of the world's poor, sick, and suffering. We are an effective means of reaching hurting people in countries around the world with food, medicine, and other assistance in the Name of Jesus Christ. This, in turn, earns us a hearing for the Gospel, the Good News of eternal life through Jesus Christ.41 Taking Senator Helms’ deeply held religious beliefs and a policy speech on HIV/AIDS before evangelical Christian philanthropists coupled with President Bush’s own well-documented religious beliefs; one quickly sees a circumstantial, albeit likely connection. Senator Helms’ and President Bush’s shared religious beliefs, their close political alliances with evangelical interest groups and the focus in 2001-2003 on HIV/AIDS make the religious motivations for PEPFAR very likely. Additionally, as recently as 2008 Samaritan’s Purse continued to support PEPFAR projects and lobby for their continued funding.42 Catholic Relief Services and many other faith based organizations also play a major role in implementation of the plan abroad. CQ Weekly has 41 Samaritan’s Purse “About Us.” Accessed at http://www.samaritanspurse.org/index.php/Who_We_Are/About_Us/ on 5 December 2009. Franklin Graham is the son of noted American Christian preacher Rev. Billy Graham. The Graham family continues to be actively involved in the evangelical Christian movement. 42 See also, Franklin Graham “Protecting PEPFAR” National Review Online 21 April 2008. Accessed at http://article.nationalreview.com/?q=YWNiZGZkMmNiODE2ZDQ2MWU1NTE1MDI3OTgwNjhiYTU=/ on 5 December 2009. 15 reported that religious organizations played a role in influencing foreign policy in the Bush White House at the time and on this issue one should expect similar alliances.43 By far the most indicative statements of President Bush’s religious motivations can be seen in his April 29, 2003 statement to push the initiative. Similar to, if not paraphrasing Senator Helms, President Bush noted: I appreciate those who are members of the faith-based world who have answered the call, the universal call, to help a brother and sister in need….When we see the wounded traveler on the road to Jericho, we will not—America will not, pass to the other side of the road.44 He continues to reference deep, moral and universal duties for the United States to meet. Lefkowitz recounts a private conversation he had with the President about the duties the United States has to meet following a meeting with survivors of the Nazi Holocaust and how deeply that affected the President’s commitment to end suffering where it was possible. Bush stated to Lefkowitz, “We are too wealthy a nation, and too compassionate a nation, not to take this step. It’s a chance to save millions of lives. We have to do this.”45 Stemming directly from the United States capacity to act, Bush was motivated to meet needs that American capacities could realistically and positively affect. One stream of influence 43 PEPFAR Report. “Celebrating Life: The U.S. President’s Plan for Emergency AIDS Relief; Fifth Annual Report to Congress” Accessed at http://www.pepfar.gov/press/fifth_annual_report/index.htm on 5 December 2009. Conservative interest in foreign policy was significant among religious organizations. The Pitts Amendment mentioned in note 15 above was likely speaking for conservative grassroots organizations who took an interest in the coupling of moral and foreign policy provisions of the PEPFAR legislation. CQ Weekly has provided a list with short descriptions of each of these religious groups which wielded some foreign policy influence in the Bush Administration and with their conservative allies. (see “Religious Organizations Wield Influence” CQ Weekly. 13 July 2002 p. 1894). 44 See Bush, “Remarks on the Global HIV/AIDS Initiative” supra. 45 Quoted in Lefkowitz, supra. 16 in motivating this policy clearly appears to be the evangelical beliefs of the President and some of his allies in the Congress. However, again breaking with the prevailing caricatures of his Presidency, George W. Bush recognized the historical place of U.S. leadership on human rights. He traces America’s belief in the dignity of life and human rights to the Declaration of Independence, noting on signing the bill one month later: America makes this commitment for a clear reason directly rooted in our founding. We believe in the value and dignity of every human life. In the face of preventable death and suffering, we have a moral duty to act and we are acting.46 Bush claims that American capacity to do good for others as a prosperous, capable nation places obligations upon it for global leadership to alleviate suffering. The affordability of generic antiretroviral drugs put the massive goals of preventing 7 million new HIV/AIDS infections within the feasible reach of the United States. In the summer of 2001 an Indian company was able to offer the AIDS medication “cocktail” treatment generically for about $295 a head when it had previously cost over $10,000 a person. Political will was all that stood in the way of, as Bush put it, “helping a neighbor in need.”47 Conclusion While many legislators had significant interests in the HIV/AIDS issue, the factional differences between their various positions as to the means of addressing the crisis were not possible to overcome without some centripetal force. The U.S. Presidency has always been a 46 See Bush, “Remarks on Signing the United States Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria Act of 2003” supra. 47 Ibid. 17 centralizing force in American politics and on the HIV/AIDS issue President Bush’s deeply held commitment to addressing the epidemic in Africa was critical to overcome the more narrow differences of parochial members of Congress. The power of the U.S. Presidency to focus attention on an issue, and his control over the U.S. budgetary process makes it possible to back up philosophic commitments with hard dollars. What remains striking, however, is how deeply President Bush actually believed he had a stated moral imperative to alleviate suffering of people globally, as a God-given commandment to “love thy neighbor.” Suffering people the former President would never see, much less have as constituents, stood to benefit from his profound commitment to the cause. Regardless of his failure in other human rights issues, this one remains an area where President Bush was crucial in building a bipartisan coalition to support funding for HIV/AIDS relief in Africa and reminds us to look beyond popular caricatures when evaluating a political leader’s legacy.