It’s not Easy Being Green: Minor Party Labels as Heuristic Aids

advertisement

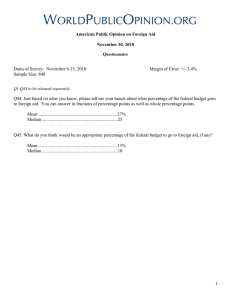

It’s not Easy Being Green: Minor Party Labels as Heuristic Aids Travis G. Coan Jennifer L. Merolla (contact author) Claremont Graduate University, Department of Politics & Policy 160 East Tenth Street Claremont, CA 91711-6168 United Status travis.coan@cgu.edu jennifer.merolla@cgu.edu Laura B. Stephenson University of Western Ontario lstephe8@uwo.ca Elizabeth J. Zechmeister University of California, Davis ejzech@ucdavis.edu ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank the IGA Junior Faculty Research Program at UC Davis for providing funding for the project, Robert Huckfeldt for the use of the experimental lab at UC Davis, faculty members who gave their class extra credit for participating in the study, and research assistants Ryan Claassen, David Greenwald, Steve Shelby, Breana Smith, and Brandon Storment. ABSTRACT This paper focuses on whether, and to what extent, minor party labels influence how individuals express opinions on a wide range of political issues. Based on data from an experimental study conducted in the U.S., we reach three conclusions: 1) partisan identification conditions the influence of party cues on political opinions; 2) individuals often ignore, and sometimes resist, minor party labels as cues; and, 3) the complexity of the political issue matters for the effectiveness of party cues. Our findings are important given recent trends in public opinion data, which indicate that the U.S. public is becoming more accepting of minor parties as permanent features of the political system. Key Word: Heuristics, Information Shortcuts, Party Cues, Minor Parties, 1 A large body of political science research focuses on the utility of cognitive heuristic devices for rational decision-making by otherwise under-informed individuals. Party labels are considered one of the most useful of such aids due to their accessibility and relevance to a variety of political decisions (Huckfeldt, Levine, Morgan, & Sprague, 1999). This rosy picture of the utility of party cues, however, has recently been questioned by several scholars of U.S. politics (e.g., Lau & Redlawsk, 2001; Lupia & McCubbins, 1998). Using experimental data, we extend work in this area by exploring whether, and to what extent, minor party labels in the U.S. influence individual opinions on a range of political issues. Focusing on minor parties is of particular importance given that their influence appears to be increasing in recent years. Among the public, there has been an increase in general dissatisfaction with the two major parties and in the percentage who think there should be “a third major party” (Collet, 1996). Furthermore, minor parties are beginning to compete in more elections, especially at the state and local levels (Lacy & Monson, 2002), and have cost major party candidates the election in some contests (Burden, 2005). Given the increasing presence of minor parties, it is fitting to ask whether they act as information shortcuts for citizens in the same way as major parties. With the exception of one study (see Lupia & McCubbins, 1998), however, the literature is theoretically and empirically silent on the effects of minor party cues. OVERVIEW OF EXTANT LITERATURE A long line of literature has argued that citizens can make reasonable choices through the use of information short-cuts, even if they possess minimal levels of information about the political world (e.g., Downs, 1957; Sniderman, Brody &, Tetlock, 1991). One common heuristic aid is the party label. Downs (1957) argued that one of the main purposes of political parties is to provide an information short-cut for voters, to help them understand the issue positions and/or 2 ideology of political actors. Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes (1960) extended this idea, arguing that the psychological attachments underlying party identifications shape political attitudes and evaluations and help individuals to establish coherent sets of political opinions (see pp. 128-136). A great deal of contemporary scholarship has investigated the use of party labels as heuristic devices in various domains. Scholars have found that people rely on partisan cues in the voting booth (e.g., Lau & Redlawsk, 2001; Rahn, 1993); in predicting the issue and ideological positions of candidates (e.g., Conover & Feldman, 1981; Huckfeldt et al., 1999; Koch, 2001); and, in forming preferences on novel issues (Kam, 2005). Given this literature, major party labels should be influential cues in the realm of opinion expression. Specifically, knowing where a party stands on an issue should influence an individual’s own stand on that issue. However, some recent work has questioned whether party cues are always useful. With respect to voting, if the positions of candidates are inconsistent with those of the party, voters are less likely to select the “correct” candidate (Lau & Redlawsk, 2001; Rahn, 1993). More generally, Lupia and McCubbins’ (1998) theoretical results suggest that party cues are only useful to the extent that they convey “information about knowledge and trust” (p. 207). From this viewpoint, the influence of party cues depends on whether the individual perceives the party as knowledgeable, and believes that the parties are being truthful. Studies of persuasion and priming also find that individuals are more likely to incorporate messages when they trust the sender of the message, especially in low information and motivation environments (e.g., Chaiken, 1980; Miller & Krosnick, 2000; Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Following this line of reasoning, some parties in the U.S. play such minor, low profile roles that the usefulness of their labels to citizens is clearly questionable. For example, while individuals may have heard of a 3 particular minor party, they may be unfamiliar with the party’s stances on many issues. Moreover, even among minor parties that are better known, the candidates running under their label often represent inconsistent positions. In either case, it is unlikely that individuals will perceive the minor party as knowledgeable and trustworthy; thus, even knowing where the party stands on an issue might not help an individual figure out his or her own stand on that issue. RESEARCH DESIGN In order to test the travelling capacity of arguments about party cues from major to minor parties, we conducted an experiment. The core of the experiment consisted of asking subjects to fill out a questionnaire about political opinions, in which we embedded issue questions with party cues. With respect to the treatments, we chose three parties to use as cues: one dominant party (Republican) and two minor parties (Green and Reform). We expected that the Green party would have a slightly better reputation than the Reform party, given Nader’s run for office in 2000 and 2004; the fact that the party takes more consistent positions; and, the geographic location of our study (see below). To create a fair test for the effect of party labels on opinion expression, we included two additional variables in the study. First, we included measures of partisanship, since one’s partisanship may moderate the effect of party labels, acting as a type of “perceptual screen” (Campbell et al., 1960, p. 133). If an individual is a strong partisan of a particular party, he/she should be more likely to accept that party’s cue while opposition partisans may reject it. Second, we included issues of various complexities, since the effectiveness of party labels may vary across types of issues (Carmines & Stimson, 1980). With easy issues, individuals are more likely to have the capacity and the time to develop opinions. As issues 4 increase in complexity, citizens might rely more on cues in the expression of their political preferences (Kam, 2005). In sum, we expect that the major party cue will influence an individual’s political opinions. Second, individuals will either ignore or resist cues from minor parties. If they do the former, the minor party cue will have little—if any—effect on political opinions; if the latter, individuals will express a policy preference that is opposite the minor party’s position. Finally, the effects of party cues will be moderated by partisanship and issue complexity. Participants and Design The participants in our study were 250 undergraduate students enrolled in political science classes at a large public university. The students volunteered to participate in the research study about political opinions and attitudes in exchange for class credit. The study took place in the Spring of 2005 in a computer lab. Subjects were randomly assigned to a treatment (Republican N=54, Green N=50 and Reform N=66) or control group (N=78 for the control group). The study consisted of a computer-based survey in which participants were asked about basic demographics, political predispositions, and their opinions on a number of political issues. The experimental condition was embedded in a series of four issue opinion questions, which varied with respect to complexity. The content of the issue questions is identified in Table I (along with the direction of the party prompt for each issue). [Insert Table I about here] Each issue question was preceded by a statement that one of the parties supported or opposed the issue. The control group received a neutral cue: “Some politicians…”. After the prompt, each subject was asked for their own opinion on the issue. For example, the abortion question read as follows in the Republican treatment: "The Republican Party supports prohibiting abortion in all 5 cases. Do you support or oppose prohibiting abortion in all cases?” If the cues work as heuristic aids in a positive sense, we should find that individuals adopt preferences in line with the given party cue (see Table I). RESULTS Before testing the treatment effects, we first assess whether perceptions of minor and major parties differ in terms of awareness and trust, as Lupia and McCubbins (1998) lead us to expect. To measure the former, we asked subjects for their familiarity with all parties and the certainty of their placement of each party on an ideological spectrum (see Table II). As expected, subjects are more familiar with and more certain of their ideological placement of the Republican Party compared to the two minor parties, and these differences are statistically significant at p<.001. With respect to trust, our measures indicate that subjects are significantly more trusting of the Republican Party compared to the Reform party (p=.055), though they record highest trust values for the Green party (p<.001). This result is due to the fact that Democrats outnumbered Republicans in our sample by a fairly significant degree (52% of the subjects identified as Democrats and 24% as Republican). Not surprisingly, strong Republicans are significantly more trusting (mean=5.14) of their party than the Greens. [Insert Table II about here] With support for our characterization of the major and minor parties, we now turn to multivariate analyses for each issue, testing the effect of different party cues on policy preferences compared to the control group. The dependent variables in the analyses consist of the respondent’s opinions on the political issues. These five-point, Likert scales are coded such that higher values indicate a more liberal response. Since the dependent variables are measured on an ordinal scale, we run ordered probit analyses. 6 In addition to dummy variables for each treatment group (the control group serves as our baseline), we include the following control variables: female (one indicates that the respondent is female), religion (a five-point scale, where higher values mean more church attendance), ideology (a seven-point scale, where higher values mean more conservative), partisanship (a seven-point scale, where higher values indicate stronger Republican identification), and the interaction between partisanship and each treatment dummy variable. The latter set of interaction terms is included to test for the moderating effects of partisanship. Ideology is a control variable because it may have a strong influence on political opinions. Female and religion are included because, in difference of means tests designed to check whether our random assignment resulted in even cross-group distributions, we found significant differences across groups with respect to these measures. The results for each issue are presented in Table III. We report one-tailed tests for individuals in the Republican treatment group as we expect these individuals to move in the direction of the Republican Party cue, subject to partisanship. We report two-tailed tests for subjects in the minor party treatment groups, as we expect individuals to ignore or resist the minor party cues. Given the presence of interaction terms in the model, the results are supplemented by Table IV, in which we calculate the slope of each treatment at each level of the moderating variable of partisan identification. Since the coefficients from the ordered probit estimations are not directly interpretable, Table IV also includes the first differences generated using Clarify (King, Tomz, & Wittenberg, 2000; Tomz, Wittenberg & King, 2001). We report the change in the probability of falling into the most liberal category, when one moves from the control group to one of the treatments, at each category of partisanship. 7 Turning first to the Republican treatment, the cue is insignificant for the abortion and services issues. With respect to imports, the cue is just outside of traditional significance levels for strong Republicans (p =.11). For the class action issue, the treatment is significant for Independents (p<.10) and Republican identifiers (p<.05). Individuals accept the Republican information cue in both cases—i.e., they take a more conservative position relative to their counterparts in the control group. These findings are somewhat supportive of the moderating effects of issue complexity and partisanship, as significant results are only obtained among Independents and Republicans and only for the two more complex issues. However, the substantive effects are not substantial. For example, receiving the Republican treatment reduces the probability of falling into the most liberal category by only 3 percentage points for the imports issue and 2 percentage points for the class action issue among strong Republicans. Turning next to the Green party, the results indicate that the treatment is insignificant for the abortion and class action issues. The treatment is significant for almost all partisan groups (with the exception of strong partisans) for the services issue. The direction of the coefficient suggests that, in this case, individuals resist the party cue. For the imports issue, we find that weak and strong Republicans reject the cue, becoming more entrenched in the conservative position, relative to their counterparts in the control group. The substantive effects are a bit higher than they were for the Republican cue. For example, weak Republicans in the Green treatment are 7 percentage points less likely to fall into the most liberal category for the services issue, while the comparable effect for the imports issue is only 2.7 percentage points. Lastly, the Reform party treatment fails to reach statistical significance for the abortion, services, and class action issues. For the imports issue, the Reform treatment is significant for all those with Democratic sympathies. As with the Green party treatment, for this issue, Democrats 8 and Independents reject the Reform party cue. The substantive effects, however, are minimal at best—individuals receiving the treatment are not even 1 percentage point less likely to fall into the most liberal category. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION Our findings for the major party cue are generally consistent with the extant literature. We did not expect this party cue to be influential for the easier issues. As the policy issues became more complex, however, the Republican treatment became more important in predicting policy opinions, which is consistent with the literature (e.g., Kam, 2005). Furthermore, we found support for the moderating effect of party identification in that Democrats were not persuaded by the cue. Interestingly, while we find that the minor party cues are significant more often than the major party cue, we also find that in all cases where the minor party cues are significant, subjects act against the cues. For instance, individuals reject the Green cue for the services issue, and reject the Green and Reform cues for the imports issue. These results support Lupia and McCubbins’ (1998) argument that obscure parties are not perceived to be reliable cues, and suggest an even stronger assertion: minor party cues work as negative heuristics or indicate to individuals what policy position not to take. More generally, the results indicate that familiarity with a cue giver, as well as trust, are both important conditions for persuasion via heuristic based processing. 9 References Burden, B. C. (2005). Minor Parties and Strategic Voting in Recent U.S. Presidential Elections. Electoral Studies, 24, 603-618. Campbell, A., Converse, P.E., Miller, W.E., & Stokes, D.E. (1960). The American Voter. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Carmines, E.G. & Stimson, J.A. (1980). The Two Faces of Issue Voting. The American Political Science Review, 74, 78-91. Chaiken, S. (1980). Heuristic versus Systematic Information Processing and the Use of Source verses Message Cues in Persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 752-766. Collet, C. (1996). Trends: Third Parties and the Two-Party System. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 60, 431-449. Conover, P.J. & Feldman, S. (1981). The Origins and Meaning of Liberal/Conservative SelfIdentifications. American Journal of Political Science, 25, 617-645. Downs, A. (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper and Row. Huckfeldt, R., Levine, J., Morgan, W., & Sprague, J. (1999). Accessibility and the Political Utility of Partisan and Ideological Orientations. American Journal of Political Science, 43, 888-911. Kam, C.D. (2005). Who Toes the Party Line? Cues, Values, and Individual Differences. Political Behaviour, 27, 163-182. King, G., Tomz M., & Wittenberg, J. (2000). Making the most of statistical analyses: Improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 347-61. 10 Koch, J.W. (2001). When Parties and Candidates Collide: Citizen Perception of House Candidates’ Positions on Abortion. Public Opinion Quarterly, 65, 1-21. Lacy, D. & Monson Q. (2002). The Origins and Impact of Voter Support for Third-Party Candidates: A Case Study of the 1998 Minnesota Gubernatorial Election. Political Research Quarterly, 55, 409-37. Lau, R.R. & Redlawsk, D.P. (2001). Advantages and Disadvantages of Cognitive Heuristics in Political Decision Making. American Journal of Political Science, 45, 951-971. Lupia, A. & McCubbins, M.D. (1998). The Democratic Dilemma: Can Citizens Learn What They Really Need to Know? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Miller, J.M. & Krosnick, J.A. (2000). News Media Impact on the Ingredients of Presidential Evaluations: Politically Knowledgeable Citizens are Guided by a Trusted Source. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 301-315. Petty, R.E. & J.T. Cacioppo (1986). Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change. New York: Springer-Verlag New York, Inc. Rahn, W.M. (1993). The Role of Partisan Stereotypes in Information Processing about Political Candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37, 472-496. Sniderman, P.M., Brody, R.A., & Tetlock P.E. (1991). Reasoning and Choice: Explorations in Political Psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Tomz, M., Wittenberg J., & King, G. (2001). CLARIFY: Software for interpreting and presenting statistical results. Version 2.0. Cambridge: Harvard University [software online; available from http://gking.harvard.edu.] 11 Table I: Issues Questions and Direction of Prompts (with expected sign in parentheses) Type of Issue U.S. Prohibit abortion in all cases Easy Republican: Support (-) Green: Oppose (+) Reform: Oppose (+) Decrease services and spending Easy Intermediate Republican: Support (-) Green: Oppose (+) Reform: Support (-) Place more limits on imports Hard Intermediate Hard Republican: Oppose (-) Green: Support (+) Reform: Support (+) Limit class action law suits and move many from state to federal courts Republican: Support (-) Green: Oppose (+) Reform: Oppose (+) *The sign in parentheses reflects the anticipated effect after the variables were recoded such that higher values indicate more liberal responses, and reflect only the situation in which those receiving the cue are persuaded to adopt stances in accord with that party’s stance (as compared to those in the control group). 12 Table II: Summary Statistics for Familiarity and Trust N Mean Familiarity Republican Party 250 4.168 Democratic Party 250 4.408 Green Party 250 3.060 Reform Party 250 2.320 Ideological Certainty Republican Party 250 4.772 Democratic Party 250 4.796 Green Party 250 3.892 Reform Party 250 2.364 Trust Republican Party 249 3.434 Democratic Party 249 3.831 Green Party 247 3.065 Reform Party 181 3.420 Republican Party 110 2.845 Trust by Party ID Republican Party Strong Democrat 49 2.163 Weak Democrat 78 2.718 Lean Democrat 34 2.441 Independent 13 2.769 Lean Republican 13 3.615 Weak Republican 38 4.211 Strong Republican 22 5.136 Green Party Strong Democrat 39 3.872 Weak Democrat 56 3.482 Lean Democrat 25 4.120 Independent 8 3.000 Lean Republican 11 2.727 Weak Republican 23 3.043 Strong Republican 19 2.421 Reform Party Strong Democrat 15 2.600 Weak Democrat 36 3.083 Lean Democrat 13 2.923 Independent 7 2.143 Lean Republican 7 2.286 Weak Republican 16 3.125 Strong Republican 16 2.750 Std. Dev. 0.975 0.837 1.189 0.949 Min 1 1 1 1 Max 6 6 6 5 1.018 0.937 1.804 1.643 1 1 1 1 6 6 6 6 0.901 1.090 1.404 1.160 0.930 1 1 1 1 1 6 6 6 6 5 0.986 1.216 1.211 1.301 0.768 0.811 0.774 1 1 1 1 2 2 4 4 6 4 4 5 6 6 0.978 0.786 1.333 1.773 1.104 0.976 1.170 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 6 5 6 5 4 4 4 0.828 0.806 1.188 1.069 0.756 0.619 1.125 1 2 1 1 1 2 1 4 5 4 3 3 4 4 13 Table III. Effectiveness of Party Cues in Opinion Expression, Ordered Probit Results Republican Treatment (T) Green T Reform T PID Republican T * PID Green T* PID Reform T*PID Ideology Religion Female _cut1 _cut2 _cut3 _cut4 N Pseudo R2 LR chi2 (10, 11) Prob > chi2 Easy Issue: Abortion 0.378 (0.335) -0.502 (0.310) -0.091 (0.310) 0.075 (0.080) See Table 4 See Table 4 See Table 4 -0.170 *** (0.084) -0.239 *** (0.061) 0.311 ** (0.152) -3.605 (0.360) -3.002 (0.337) -2.678 (0.330) -1.709 (0.312) 233 .128 79.87 .000 Easy Intermediate Issue: Services -0.112 (0.316) -0.449 (0.273) 0.040 (0.290) -0.184 ** (0.078) See Table 4 See Table 4 See Table 4 -0.073 *** (.077) 0.105 * (0.060) 0.180 (0.148) -3.213 (0.338) -2.066 (0.298) -1.525 (0.289) -0.034 (0.304) 230 .130 83.67 .000 Hard Intermediate Issue: Imports 0.313 (0.318) 0.439 (0.319) -0.572 * (0.307) 0.118 (0.082) See Table 4 See Table 4 See Table 4 -0.150 * (0.082) 0.119 * (0.065) 0.230 (0.156) -1.686 (3.17) -0.231 (0.293) 0.718 (0.330) 2.480 (0.396) 204 .038 20.01 .019 Hard Issue: Class Action 0.095 (0.346) 0.158 (0.339) -0.147 (0.333) -0.018 (0..085) See Table 4 See Table 4 See Table 4 0.081 (0.082) -0.115 * (0.069) 0.200 (0.166) -2.612 (0.386) -0.798 (0.316) 0.570 (0.312) 2.217 (0.385) 187 .024 10.25 .419 ***p≤0.01, **p≤0.05, *p≤0.10 Note: See Table IV for the slope of each treatment at each level of partisan identification. 14 Table IV: Effectiveness of Party Cues in Opinion Expression, Ordered Probit Results (Effect of Treatment at Different Levels of Party Identification) Party ID Strong Democrat Weak Democrat Lean Democrat Independent Lean Republican Weak Republican Strong Republican Party ID Strong Democrat Weak Democrat Lean Democrat Independent Lean Republican Weak Republican Strong Republican Party ID Strong Democrat Weak Democrat Lean Democrat Independent Lean Republican Republican Cue 0.378 (0.335) 0.270 (0.263) 0.162 (0.219) 0.054 (0.221) -0.054 (0.268) -0.162 (0.342) -0.270 (0.429) Republican Cue -0.112 (0.313) -0.079 (0.302) -0.046 (0.326) -0.013 (0.378) 0.020 (0.449) 0.053 (0.532) 0.085 (0.621) Republican Cue 0.313 (0.318) 0.169 (0.249) 0.025 (0.212) -0.119 (0.224) -0.263 (0.277) Easy Issue: Abortion First Green First Difference+ Cue Difference+ 0.145 -0.502 -0.178 (0.310) 0.104 -0.357 -0.136 (0.241) 0.063 -0.212 -0.084 (0.210) 0.021 -0.067 -0.028 (0.232) -0.021 0.078 0.027 (0.297) -0.062 0.223 0.077 (0.382) -0.100 0.368 0.118 (0.477) Easy Intermediate Issue: Services First Green First Difference+ Cue Difference+ -0.040 -0.449 -0.144 (0.297) -0.024 -0.505** -0.135 (0.232) -0.012 -0.561*** -0.123 (0.210) -0.002 -0.617** -0.105 (0.241) 0.006 -0.673** -0.087 (0.310) 0.011 -0.729* -0.070 (0.397) 0.015 -0.785 -0.054 (0.494) Hard Intermediate Issue: Imports First Green First Difference+ Cue Difference+ 0.010 0.440 0.016 (0.318) 0.006 0.220 0.007 (0.249) 0.001 0.000 0.000 (0.221) -0.004 -0.220 -0.008 (0.249) -0.011 -0.440 -0.016 (0.318) Reform Cue -0.192 (0.310) -0.116 (0.247) -0.002 (0.210) 0.165 (0.212) 0.375 (0.253) 0.605 (0.318) 0.845 (0.395) First Difference+ -0.034 Reform Cue 0.040 (0.290) 0.025 (0.228) 0.010 (0.190) -0.005 (0.190) -0.020 (0.228) -0.035 (0.290) -0.050 (0.363) First Difference+ 0.015 Reform Cue -0.572** (0.307) -0.486** (0.243) -0.400** (0.205) -0.314 (0.207) -0.228 (0.249) First Difference+ -0.007 -0.010 0.020 0.048 0.075 0.098 0.117 0.010 0.005 0.002 -0.001 -0.003 -0.004 -0.008 -0.009 -0.010 -0.011 15 Weak Republican Strong Republican Party ID Strong Democrat Weak Democrat Lean Democrat Independent Lean Republican Weak Republican Strong Republican -0.407 (0.355) -0.551 (0.444) Republican Cue 0.095 (0.346) -0.045 (0.272) -0.185 (0.228) -0.325* (0.232) -0.465** (0.283) -0.605** (0.361) -0.745** (0.452) -0.020 -0.660* -0.027 (0.407) -0.032 -0.880* -0.040 (0.507) Hard Issue: Class Action First Green First Difference+ Cue Difference+ 0.008 0.158 0.014 (0.339) -0.002 0.099 0.008 (0.438) -0.009 0.040 0.003 (0.734) -0.014 -0.019 0.001 (1.075) -0.017 -0.078 -0.004 (1.429) -0.020 -0.137 -0.006 (1.789) -0.023 -0.196 -0.008 (2.151) -0.142 (0.315) -0.056 (0.392) -0.010 Reform Cue -0.147 (0.333) -0.115 (0.265) -0.083 (0.226) -0.051 (0.232) -0.019 (0.281) -0.013 (0.355) 0.045 (0.442) First Difference+ -0.008 -0.006 -0.007) -0.005 -0.003 -0.002 -0.000 0.001 ***p≤0.01, **p≤0.05, *p≤0.10 (One-tailed tests for Republican treatment and two-tailed for the minor parties) Note: We used Clarify to calculate these first differences. Numbers in cells are based on the model presented in Table III. In all cases, female is held constant at its maximum value (1) and the ideology and religion variables are held constant at their mean values. 16