Why Don’t They Use Just Words?

advertisement

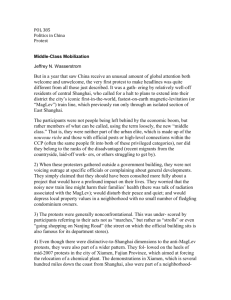

Why Don’t They Use Just Words? Accounting for Indian Political Protest on the Streets and in Parliament By Dean E. McHenry, Jr. Claremont Graduate University A paper prepared for delivery at the Association for Asian Studies Annual Meeting, Boston, March 22-25, 2007 Abstract India is faced with countless protests and agitations each day—both outside and inside its legislative bodies. The question we address is “Why is this occurring?” After reviewing examples of such protests/agitations, their scope and the threat they pose to Indian democracy, a variety of explanations is presented and assessed. All seem to capture part of the reality, but none seems to account for the phenomena generally. The continuing challenge is to decipher the unique meanings of the protests and agitations out of the individual contexts within which they occur. 2 Why Don’t They Use Just Words? Accounting for Indian Political Protest on the Streets and in Parliament By Dean E. McHenry, Jr. Claremont Graduate University “‘Over the years what has developed is the notion that an issue, demand or agitation is highly successful if it can lead to stoppages in the House, as if that were the pinnacle of protest. This is highly unfortunate,’ the Speaker of the Lok Sabha, Somnath Chatterjee, has said. ‘None, no particular party, is totally free from this concept. Once an adjournment is forced, members go out with the claim that the matter at hand is so important that even the House could not function. Unfortunately, the confrontationist attitude in politics outside the House finds a reflection inside it….’”1 I. Introduction There is no democracy in the world where political protest/agitation so extensively permeates the polity as it does in India.2 No day passes without significant ‘street’ protests/agitations over some type of issue in many parts of the country. No session of parliament or state assemblies passes without major disruption caused by protesting/agitating MPs or MLAs. Protests/agitations take a very wide range of forms outside parliament including bandhs, hartals, gheraos, yatras, rokos and fasts, while inside parliament they include shouting, invading the well, symbolic dress and walk-outs. As protests/agitations moved from outside parliament to inside parliament, scholars expressed their concerns that the violation of India’s laws and rules of decorum inherent in many protests/agitations are threats to Indian democracy. Although most commentators refer to India as the world’s largest democracy and a quantitative measure of democracy like Freedom House rates it as “Free” and like Polity IV as scoring a 9 out of 10, the concern is that the threat is becoming more serious. Protests/agitations seem to be displacing words as the medium of political struggle in India. The question asked in this paper is: “Why has politics taken this form?” We will approach an answer by first describing and assessing the significance of the problem of protest/agitation inside and outside parliament poses. Then we will describe and assess a variety of explanations. The major focus will be on protests/agitations taking place inside legislatures for they seem to be the ones with the greatest potential for adversely affecting Indian democracy. Our effort will be interpretive because of the complexity of the subject matter and the centrality of determining meanings of events and activities in the pursuit of an answer. 3 II. Significance Twenty years ago Marion Weiner pointed out “The Indian Paradox” where there was violent social conflict and democratic politics.3 He accounted for this in a variety of ways: the conflict-managing role of the Congress party, the bureaucrats who have a vested interest in democracy’s maintenance, the development of other political institutions, the balance of power between the states and the center, and the heterogeneity within states.4 Much of this has changed in the years since, though democracy has persisted. The Congress party no longer dominates the country the way it used to, liberalization and privatization has affected the bureaucracy to some extent, the parliament no longer functions as it did when he wrote, the balance of power is shifting toward the states. Our focus is on non-violent protest/agitation, rather than violent social conflict. Nevertheless, we would argue that essential elements of Weiner’s explanation should have applied to such protest/agitation. That these explanations seem to have been undermined by events over the last twenty years suggests the need for a continuing search. The search for an explanation for protest/agitation may provide an explanation of the paradoxical existence of the persistence of democracy in the face of what appears to be behavior that would undermine that democracy. If the causes are not contradictory to some form of democracy, then protest/agitation may not contradict democracy’s evolution. Non-violent protests/agitations were important tools in the struggle for Indian independence. Gandhi’s use of them is widely celebrated. Yet, they were not abandoned in the years following 1947. Writing in the 1960s, A.R. Desai observed, The movements of public protests not merely continue even after the establishment of a Parliamentary democracy in India, but as some observers like Bayley, Kothari, Harrison, Weiner and others have indicated, these movements have been increasing in number and have been gathering momentum, threatening even the very existence of the Parliamentary Government which has emerged in India after the British withdrawal.5 They continue to be an important feature of Indian life. Although they were widely used, they were not employed in Indian legislatures for many years after independence. Gradually, though, they became a dominant feature at both the center, in the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha, and in the state assemblies, the Vidhan Sabha. The shift of protest/agitation into legislative bodies over the last few decades has been attributed to a simple cost/benefit calculation by political leaders. The editors of The Hindu, referring to the disruption of the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha by the Opposition over a demand that a minister resign because of errors committed by his ministry, complained that “the parties had hardly done their mite outside Parliament to organize demonstrations and grass roots activity in favour of their position….” and that, “…stalling parliamentary proceedings— 4 all that it requires is for a few members to walk into the well of the House—is indeed an easy way out.”6 That is, the cost/benefit ratio to the disrupters is much greater than would be protest/agitation outside legislatures. Parliamentarians themselves may shift the protest/agitation outside parliament itself in order to increase the cost/benefit ratio further. For example, in the Kerala Legislative Assembly in August of 2002, the Speaker “in his wisdom, decided that the public need not see the Opposition using placards instead of debating skills in the House.”7 He did not want to give publicity to the position of the Opposition as its members disrupted the session. But, the Opposition learned from the experience. On the final day of the session when a Bill they opposed came up for its third reading, they boycotted the Assembly and gathered outside the building. There they publicly burned the Bill. As noted by a reporter, “The news bulletins of the visual media carried the event while the visuals of the historic occasion of passing of the Bill was confined to the closed circuit televisions of the House, watched mostly by the private staff of the Ministers.”8 A. Illustrations of protests/agitations Hundreds of protests/agitations affect Indian legislatures and thousands affect life outside such legislatures each year. To get a sense of what is involved, consider the three following cases selected randomly: 1. In Tamil Nadu’s Legislative Assembly A DMK member was suspended from the Assembly for the remainder of the budget session for tearing up a policy paper on the police department near the Speaker’s chair in April of 2003. A press report described what followed: [T]he DMK deputy leader in the Assembly, Durai Murugan, contended that it was an accepted form of democratic protest. Mr. Karunanidhi said there were many such instances in the past, both in Assemblies and in Parliament, but no one was suspended for an entire session just for that reason. 9 In addition, the DMK withdrew from participation in the Assembly for the rest of the session. Mr. Karunanidhi said that He did not consider the DMK decision an extreme step. As the party was prevented from performing its democratic duty inside the House, it was left with no choice.10 With the DMK boycotting the Assembly, the remaining opposition brought up an array of other issues and demanded that the Speaker “adjourn the question time and allow a debate on issues of ‘survival’ of the government employees and deprivation of the rights of MLAs.”11 The Opposition continued to argue “and all Congress MLAs rose to launch into full-throated slogan shouting.” 5 “Don’t file false cases against the Opposition, drop vindictive action, don’t deprive government staff of their pension benefits,” they screamed, plunging the House into bedlam. And, soon CPI and CPI(M) members also joined the sloganeering. The Speaker’s warning to the Opposition MLAs to behave with dignity and not to reduce the House to a roadside public meeting went unheeded. And, the Opposition MLAs only hit a higher decibel of slogan-shouting. The Speaker then directed the Leader of the House to move a resolution to evict them and Treasury benches said “yes.” In a few seconds, the watch and ward staff swooped on the Opposition MLAs, most of whom walked out without much resistance. But C. Gnanasekaran (Congress), who spread out on the seat, was bodily lifted out. But the expulsion …was quickly followed by a 10-minute, noisy sit-in protest in the lobby, a fiveminute lying-down stir by a few members in the corridor outside the House and a 10 minute-dharna on the middle of Rajaji Salai. The protests in the forenoon culminated in the arrest of the 43 MLAs from the outgate of the Secretariat and their detention in nearby North Beach police station, from where they were let off at 1 p.m.12 2. In the two houses of parliament in New Delhi During the visit by President Bush to India in March of 2006, disruptions occurred in the both the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha. A press report described it as follows: Agitated Left MPs as well as those from SP shouted slogans against Mr Bush’s visit in both Houses of Parliament from the moment proceedings began this morning, forcing adjournments in the first half of the day’s business. SP members, wearing red caps, trooped into the Well of Lok Sabha. They were joined by Left MPs in raising slogans like, “Bush go back.” Even before Parliament began its business for the day, MPs of the four Left parties and the SP staged a sit-in inside Parliament complex to express their opposition to Mr Bush’s trip. Holding placards with slogans such as “War criminal Bush go back”, “UPA government stop surrendering to US imperialism” and “Killer bush”, the MPs as well as senior leaders from their parties shouted slogans against the USA. Describing Mr Bush as “the biggest enemy of Humanity” and the “biggest killer of the 21st century,” CPI-M MP Mr Hannan Mollah said: “Bush should have no 6 place in India; he should not be allowed to come and spread his tentacles on our soil.”… The Left leaders later went to Ramlila Ground to participate in a massive demonstration against the Bush visit.13 3. In Andhra Pradesh’s Legislative Assembly At about the same time in the Andhra Pradesh Legislative Assembly, following the Government’s decision to countermand a byelection in Visakhapatnam-I constituency, a press report described the scene as follows: As soon as the proceedings began, the TDP and five other parties created noisy scenes by tabling separate adjournment motions. The BJP too alleged failure of the Government machinery in ensuring a free and fair election. All the six motions were disallowed by Speaker K.R. Suresh Reddy. This led to an uproar with TDP members shouting and the Congress countering them with slogans. This forced the Speaker to adjourn the House for early 90 minutes during which time he convened a meeting of the floor leaders to find a way out of the impasse. However, the TDP did not yield from its demand that the Chief Minister step down…. When the House reassembled, the TDP members rushed into the well holding aloft placards. In the din caused by acrimonious exchanges between TDP and Congress members, the Speaker asked Finance and Legislative Affairs Minister K. Rosaiah to reply to the discussion on the State budget. As the TDP members disrupted the Minister’s speech, the Speaker named them. Taking the cue, Mr. Rosaiah moved a motion for their suspension from the House for two days. After the motion was passed by voice vote amid thumping of desks by Congress members, marshals entered the House and forcibly removed TDP members. Some of them had to be bodily lifted.14 In all, 31 TDP members were suspended. These descriptions of a protest/agitation in the legislative bodies in Tamil Nadu, at the center, and in Andhra Pradesh are typical of what has become an almost constant feature of legislative life in India. B. Scope of protests/agitations Scholars who are familiar with India know that protests/agitations are daily occurrences. A.S. Desai, whose observations we have cited above, is not alone in his view that independence did not put an end to such activities—indeed, they seemed to have become more common. David Bayley observed many years ago: “The number of demonstrations, strikes, hartals, satyagrahas, and fasts held each year is almost beyond numbering.”15 It is very rare that any Indian newspaper on any day will not have reports 7 of non-violent protests/agitations in several parts of the countries. The University of Kerala scholar, J. Prabhash, wrote recently about MPs and MLAs: Today, the specializations of members, both at the Central and State levels, irrespective of flag and shade, is in the sub-disciplines of pandemonium and boycott. Both of these arts have been perfected into fine tools for disrupting legislative proceedings.16 Mohammad Yasin and Srinanda Dasgupta suggest that the increased use of such techniques, i.e., the “diversification in the nature and proliferation of protest movements in India,” is due to “(a) divergence in the targets of attack, that is, political authority, economic exploitation, cultural domination, and (b) varying perceptions about the immediate targets of attack.”17 Their spread into legislative bodies, though, became significant only in the last couple of decades. As a consequence of this change, the Lok Sabha began to keep track of the time lost by disruptions. Table I indicates the proportion of the time of the Lok Sabha, the most important legislative body in the country, taken up by disruptions over the last 15 years: Table I Summary of the Proportion of the Sitting Time of the Lok Sabha Lost to Disruptions, 10th through the 8th Session of the 14th Lok Sabha Lok Sabha Number and Duration Percent of Sitting Time Lost to Disruptions 10th (July, 1991-February, 1996) 9.95 11th (May, 1996-December, 1997) 5.26 12th (March, 1998-April, 1999) 10.66 13th (October, 1999-January 2004) 22.40 14th (First 8 Sessions, June., 2004-Aug., 2006) 38.00 Source: For the 10th Lok Sabha, Subhash C. Kashyap, History of the Parliament of India, Vol. VI (Delhi: Shipra Publications for the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi, 2000), p. 208. For the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th Lok Sabha, “Frayed tempers cost Parliament dear: Report,” Deccan Herald, January 20, 2006. URL: http://www.deccanherald.com/deccanherald/jan202006/update1027442006120.asp Accessed February 5, 2007. A recent cartoon depicted the frustration of members of the Rajya Sabha over the failure of the press to report the disruptions they had in that body. 8 Figure I We are equally staging walkouts, creating uproar, ruckus, stalling proceedings... why this discrimination? The media is not covering us like the Lok Sabha! Source: Deccan Chronicle on the Web, March 16, 2007. URL: http://www.deccan.com Accessed March 15, 2007 The growth of legislative disruptions due to protests/agitations has been described by Inder Malhotra, who has observed parliament from the first session of the “provisional Parliament” in February 1950 to the present. Writing in 2004, he asserts “the unimpeded decline in the standards of parliamentary behaviour that – combined with a relentless confrontation between the ruling party or combination and the Opposition – has inevitably taken a heavy toll.”18 He said it started in the mid-1960s, “But even in my worst nightmares I had never thought that things would descend to the lowest depths that they have.”19 He concludes: In Pakistan, Bangladesh, Myanmar and sundry other countries, Parliaments have been locked up by military dictators, often more than once. Must it be the ignominy of the world’s largest democracy that parliament here is being shut down by eminent parliamentarians themselves?20 The trend was the subject of an editorial in the Deccan Herald which contended that “…it is unfortunate that political parties always consider disruption of Parliament and state legislatures to be the best and most effective forms of expressing protest and over the years it has become the most preferred form of agitation against governments.”21 The editorial addressed, too, the reasons for the trend: “This may be partly because blockading is easy to do, does not require any special organizational efforts and is assured of good publicity. It may also be because the regard and respect for Parliament and other democratic institutions has diminished over the years and the nature of politics has changed.”22 9 In summary, the scope of Indian protests/agitations inside and outside legislative bodies is great—certainly greater than that in any other country in the world rated as a democracy. C. Threat posed by protests/agitations The threat to democracy posed by these protests/agitations has been the subject of many warnings by numerous observers. The concerns expressed were either because of the contemporary situation or the trajectory of what protests/agitations sought. • In early March of 2005, in both Houses of Parliament, the BJP protested against political events in Jharkhand and Goa and demanded the recall of the Governors. In the Lok Sabha, the Opposition “trooped into the well, shouting slogans.” “Through the din,” the Speaker adjourned the House, but before doing so he pleaded in anguish: Today is another very sad day for Indian Parliament. Our democracy is under challenge now. I appeal to all sections of the House not to liquidate democracy. We should not participate in the liquidation of democracy and denigrate Parliament any further.23 • Najma Heptulla, the Deputy Chairperson of the Rajya Sabha in 2001, noted that the lack of decorum and discipline in Parliament “is almost endangering our democratic institutions….”24 • According to G.M.C. Balayogi, Speaker of the 13th Lok Sabha, The orderly conduct of Legislatures is conducive to the growth of democracy. To serve and survive, Legislatures must function effectively so as to instill faith and confidence among the people. This is possible only if they function smoothly and meaningfully in the larger interest of the people. The growing incidents of indiscipline being witnessed in recent times in our Legislatures do not augur well for democracy.25 • Former Prime Minister, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, has argued similarly. He observed, “If the proceedings of the Parliament and the State Legislatures are not conducted in a disciplined and dignified manner, a bad example is set before the country. A sense of disregard is created for the parliamentary democracy.”26 • Krishan Kant, the Vice President of India and Chairman of the Rajya Sabha, observed in 2001 that “Each time the Parliament and the legislatures are plunged in anarchic chaos, the edifice of democracy is a little weakened.”27 10 • Leslie Calman, writing about the Maharashtra Shramik Sanghatana and Bhoomi Sena movements in the 1970s and early 1980s, contended that, at the time, the protests/agitations seemed unlikely to harm India’s democracy, but warned that The demands, eventually, could outstrip government’s capacity to respond. The government might then cease to be legitimate in the eyes of many of its citizens and would rest more heavily on force. While a government relying primarily on force to maintain itself in power is possible, it is a much shakier pedestal on which to rest.28 The list could go on and on for there is widespread concern that the protests/agitations, especially in the legislatures, threaten Indian democracy. III. Explanations We consider six general explanations, though these do not exhaust those that have been proposed. They concern the setting of the protest/agitation, the people affected, the legislators involved, the failure of alternative means, the goal of representation, and the goal of power. Most of the more complete explanations involve combinations of these. The six were selected because they encompass the most widely postulated reasons for protest/agitation. A. The setting: cultural explanations That the cultural tolerance for protest/agitation is higher in India than in many other countries is a widely accepted observation. As David Bayley observed nearly 40 years ago: Public protest is a habit….Demonstrators are as much a part of the scene around legislative buildings as cornices and arches….Politics feeds upon drama; since the requirements of drama are higher in India than in the West, it is more imperative for the Indian political party to get out into the streets than it would be for a Western party.29 Leslie Calman, commenting on two movements in the 1970s and 1980s in Maharashtra, observed that “Bhoomi Sena and Shramik Ssanghatana have utilized tactics that echo a legitimate Indian political tradition: nonviolent direct action against intransigent government.”30 What made protest a “habit” or a “legitimate Indian political tradition” normally is attributed to Gandhi’s use of satyagraha during the independence struggle. Suman Kwatra has noted that Gandhi believed that satyagraha could be used for resisting any injustice—large or small, for bringing about reform in an institution or society, fir the repeal of any unjust or bad laws for the removal of any grievances; for the prevention of communal riots or disturbances; for bringing 11 about change in the existing system of government; for resisting an invasion or for replacing one government or another.31 Yet, according to some observers, politicians have used the cultural acceptance of Gandhian techniques of protest/agitation for their own purposes. David Cortright observes that The goal of political struggle…is to reach agreement for the sake of social betterment. Political power is not an end in itself but a means of enabling people to better their condition…The notion of obtaining political power for personal gain was completely alien to him.32 Pawan Kumar Bansal writes in a similar vein: It is a common experience that today many protests are launched in the name of Satyagraha. That is a travesty of truth. In the real sense, such actions cannot be called “Satyagraha” because those who take to such protests are not fit or trained and disciplined to do so. Therein lies the danger of such make-belief or selfserving Satyagrahis degenerating into ‘Duragrahis’.33 Thus, part of the legitimacy of protest/agitations was the ends for which they were used, e.g., independence, ending exploitation, blocking government policy detrimental to large segments of the population, were beneficial to a significant group of people. The means became a part of the culture—they were viewed as a legitimate, and often effective, way of articulating a political position. Many of those concerned about their use inside and outside legislatures in India today contend that means legitimated because of their use for ends that widely benefited the people are now often being used for ends which benefit primarily the politicians that use them. In the long run, their popular legitimacy may be undermined for this reason. At present, though, one of the reasons for their frequent use appears to be their cultural legitimacy. B. The people: deprivation explanations According to Yasin and Dasgupta, the most common explanation for the use of protests/agitations is the discontent of the masses. Although they do not address parliamentary disruptions by protests/agitations, the justifications given by participants in parliament normally reference the demands of the public. They observe: In all these theories what is common is the prime emphasis on the participants of a movement. The assumption is that if the people feel deprived of, or are under strain due to malfunctioning of the system, or feel the necessity for cultural revitalization, the movement will emanate, as if other factors and conditions of the movement will automatically follow.34 Although they do not accept the primacy of such explanations, they seem to accept that popular frustration may be a contributing factor. 12 Implicit in these explanations is the idea that the normal procedures of voting and verbally urging representatives to act don’t work well in India—at least for those who resort to protests/agitations. Marxist observers tend to agree with the impetus for protest/agitation, i.e., a system which is not solving people’s problems, but contend that repairs of the liberal democratic system will not resolve the problems. Thus, popular frustration with their situation is compounded by frustration with the system of governance itself in producing protest/agitation. A.R. Desai articulates this point of view in his criticisms of Rajni Kothari’s work. He says, Kothari, while recognizing that parliamentary government has failed, and therefore compels people to takes to Direct Action, still glorifies freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and freedom of press, which he feels are its essential features. He does not point out the truth that these freedoms in the context of a capitalist framework are accessible only to a small group of capitalists, landlords, exploiters and profiteers.35 And, he criticizes Bayley because he does not see “the deeper social forces which are transforming parliamentary democratic form into a shell inadequate to preserve and protect concrete democratic rights.”36 Desai argues, Public protests will continue till people have ended the rule of capital in those countries where it still persists…. The movements and protests of people will continue till adequate political institutional forms for the realization and exercise of concrete democratic rights are found….37 Underlying both types of explanation for protests/agitation is the view that the people are unhappy with their situation, whatever its causes, and see redemption in governmental action. The liberal democratic scholars seem to see protest/agitation as a means for redress within the existing system of governance, while the Marxist scholars seem to see protest/agitation as a means for changing the system of governance into one which may bring them redress. Both seem to see the protests/agitations as a consequence of the inability of the political system to satisfy popular discontent through the existing liberal democratic procedures. C. The legislators: interests/characteristics explanations There are two types of explanations for the extensive use of protests/agitations that focus on the legislators, one having to do with their motivation and the other with their characteristics. 13 Although Yasin and Dasgupta acknowledge that the most widespread explanation is that of a discontented population, they argue that the best explanation is not popular depravation but “leadership depravation:” …the movements under the garb of peoples’ movement seek to redress the deprivation of the leadership – deprivation of his share in the power center….In all these movements even though the cause of people’s powerlessness, injustice and deprivation was highlighted, the real motive behind the movements have been the desire of the leaders to enjoy power who could not enjoy it through the accepted legitimate means.38 We will examine this issue of power as a separate explanation because of the breadth of its application, but its relevance to the specific case of the behavior of legislators seems to fit much of what happens both inside and outside legislatures. There is frequent discussion about the “criminalization” of political leadership. That is, a high proportion of candidates for legislative bodies have various criminal charges levied against them. In recent years, “sting” operations by private internet and television networks have proof of legislative bribe-taking. The argument made is that the character trait which led to the criminal behavior of legislators has led legislators to disregard appropriate political behavior inside and outside legislative bodies. According to the columnist, S. Viswam, “The criminalization of politics has impacted so adversely on parliamentary conduct that disorderly behaviour and the display of lung power inside Parliament has now come to be the accepted phenomenon.”39 Thus, the aspirations and/or character of legislators is a third form of explanation for the use of protests/agitations in Indian politics. D. The means: “failure” explanation Associated with other explanations for the extensive use of protest/agitation is the idea that existing liberal democratic mechanisms are not working properly. They don’t overcome the hardships of many people; they do not keep politicians from self-serving behaviors; they do not work as they “should” in a democratic society. And, other institutions are not performing appropriately. Protest/agitation arises as a result of the “failure” of some of the normal mechanisms of liberal democracy. 1. Of governmental institutions Illustrative of the “failures” of the polity are the conclusions of two scholars: First, Ghanshyam Shah, in his study of the cause of the 1974 Gujarat agitations, determined that the cause involved frustration with the existing democratic institutions: 14 With their faith in the electoral system shaken, many persons advocated the need for direct action. Of the respondents of Surat, 67 per cent considered strikes, gheraos, dharnas, etc. legitimate and necessary to secure their demands….The above evidence suggests that an overwhelming proportion of the people were frustrated, found themselves helpless, and were losing faith in the present political system. They opted for direct action to solve their problems.40 Shah argued that the urban and rural poor from the early 1970s became more hopeful of bettering their lives, but “big businessmen and rich peasants….organized themselves and pressurized the government to look after their interests. The party in power, dominated by the rich, succumbed to their pressures, both at the policy and implementation levels.”41 Frustrated, they turned to direct action. Second, Leslie Calman observed more than twenty years ago that “a local leadership loyal to the institutions of party politics and democratic government…failed to provide economic growth and political power for many of India’s poor. As a result, increasing numbers are finding their political voice through movements that operate outside the channels of government and parties, and that constitute a challenge to this institutional framework.”42 Illustrative of problems or “failures” of institutions that might support the mechanisms of liberal democracy and may foster the use of protests/agitations are the courts and media: 2. Of the courts The courts have before them 25-30 million cases that have not been resolved. Part of the problem stems from the failure of other parts of the government to make needed decisions. For a variety of reasons, cases against current politicians may date from decades ago. A recent case was that of Shibu Soren, the Union Minister for Coal. He was convicted at the end of November and sentenced in early December of 2006 for a murder that occurred 12 years before. One observer contended “in actual practice the hierarchy and judicial leadership are too fragile to induce a uniform code of ethical behaviour, especially when it comes to arbitrating disputes in the political sphere. It is part of a judge's occupational hazard that demands will be made on his or her objectivity and disinterestedness….and…some of the judges allow personal likes and dislikes to over-ride judicial equanimity.”43 3. Of the media There has been considerable criticism of the role of the media in the protests/agitations in legislative bodies, claiming that reporters encourage protests/agitations. When, in December of 2004, the Speaker of the Lok Sabha proposed to have parliamentary proceedings telecast, an editorial in the Hindu asked: “Will this have a salutary effect on all MPs? Will they be more decorous knowing they are being watched? Or will they be tempted to play to the gallery?”44 Subsequent events suggested the outcome was more the latter than the former. The reason seemed to be media economics and popular interests. 15 The normal conduct of legislative bodies draws the attention of few potential buyers, watchers or listeners, so they the media want disruptions. One observer said the media manufactured “controversy as an end in itself and as a market-approved device to grab eyeballs. Investigations, probes, exposes, bombshells, special reports, and other tools in a reporter's repertoire are used to draw attention to the herald — and not to his message.”45 Similarly, Mani Shankar Aiyar has suggested, with a mixture of humor and seriousness, that The only way to induce parliamentary reporters to stop their idle gossip in the corridors and actually enter the house is to tip them off about an impending disruption of proceedings. Then they swarm into the gallery, signaling with illdisguised gestures their friends on the floor, “Yoo-hoo, here I am, so get as outrageous as you can and I assure you a box on the front page tomorrow.” 46 These two observations characterize those of many others. E. The goal of representation: democratic explanations A variety of scholars suggest that much of the protest/agitation, especially that which takes place outside legislatures, is spurred by a desire for democracy. That is, the cause of protest/agitation is the desire for democracy. Although the explanation is not applied to all forms of protest/agitation, it resonates in many of them. Protests/agitations may perform the democratic function of aggregating interests. Ghanshyam Shah in his study of the 1974 Gujarat agitations found that Different socio-economic and political groups participated in the agitation for different purposes, raising issues like corruption, blackmarketing, price rise, denationalization, rationing, civil liberties, injustice to Gujaratis and Gujarat, etc. But finally all the purposes converged on two common demands, resignation of the Chief Minister and, later, dissolution of the State Assembly. The reasons for making these demands differed from group to group. For the majority of the agitators, it was to overthrow ‘corrupt’ politicians.47 Other scholars have found a more direct democratic representation in protest/agitation. David Bayley says that the protests/agitations “if they do not fall altogether outside the bounds of democratic permissibility, at least constitute the development—or continued development—of a supplementary system of representation and redress.”48 His survey indicated that “As a general rule, the public continues to believe that demonstrations are a useful way of compelling official attention.”49 His survey showed that “when they were asked whether demonstrations were useful in getting the authorities to do the right thing or correct some wrongs, approximately half of the urban samples said they were useful….In urban areas, about one out of six people have participated in a demonstration.”50 16 Similarly, Leslie Calman, writing about the Maharashtra Shramik Sanghatana and Bhoomi Sena movements in the 1970s and early 1980s, says that the movements through strikes, demonstrations, and other forms of agitational activities, first attempt to influence the passage of laws that are beneficial to the socio-economic well-being of the tribals who predominantly make up their constituency. Once those laws are in place, the movements agitate to obtain the implementation of those laws. None of this activity, viewed narrowly, is revolutionary or illegitimate…. Because the movements’ goals for the creation of better economic conditions through the passage and implementation of improved laws are within the legitimate boundaries of political demands, and because their methods, although extra-constitutional, are also within a legitimate tradition, the movements cannot be suppressed by government without considerable political cost.51 As we have noted, many critics deny the democratic impact, though generally they do not focus on the intent or what spurred those who protest/agitate to action. F. The goal of power: political explanations The explanation for the use of protest/agitation that is most widely articulated is that which asserts that the driving force is individual and group desire for power. According to Pavan Varma contends the pursuit of power is the key to understanding political behavior in India. While Gandhi gave precedence to means, Varma argues, the Indian “social consensus” gave precedence to the end. “The end was power, and the rewards it could yield in terms of personal benefit and access to the resources of the state. All the rest were instrumentalities, of importance only in reaching that end.”52 Ironically, Varma contends, this drive fosters the pursuit of democracy. The truth…is that democracy has survived in India not because Indians are democratic, but because democracy has proved to be the most effective instrument for the cherished pursuit of power. A people stifling in the pressure cooker of a hierarchically sealed society embraced the machinery of democratic politics for the promise it held of upward mobility within the inherited framework of an undemocratic society.53 Many scholars have contended that the impetus for protest/agitation lies in the drive for power. Yasin and Dasgupta have posited what they call the “Theory of the Relative Deprivation of Elites of the Deprived.”54 They argue, the movements under the garb of peoples’ movement seek to redress the deprivation of the leadership – deprivation of his share in the power center….In all these movements even though the cause of people’s powerlessness, injustice 17 and deprivation was highlighted, the real motive behind the movements have been the desire of the leaders to enjoy power who could not enjoy it through the accepted legitimate means.55 In other words, protests do not originate; they are made to originate and are imposed on the passive, ignorant masses….consciousness is created, mobilized and imposed by the few on their own narrow interest but garbed as universal interest for legitimacy. Political elites exploit situation of regional deprivation and unrest and convert them into movements to forge and strengthen their individual and factional support bases. In other words, political leaders excite regional or nativist sentiments for their political ends.56 That power is a key motivating factor in protests/disruptions is implicit in much that transpires in India’s legislatures. A few examples are illustrative. • In late 2006, in New Delhi: “The main Opposition BJP attacked Prime Minister Manmohan Singh on his remarks at the National Development Council that the minorities, particularly Muslims, must have first claim to the country’s resources, leading to pandemonium in both Houses of Parliament. The Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha were adjourned repeatedly without transacting any business. The BJP and Shiv Sena wanted the Prime Minister to apologise for his remarks, but the government turned it down.”57 The act of apologizing is viewed as an act of submission, a portrayal of the power of those who demanded it. Often legislative bodies are disrupted in support of demands for apologies. • At about the same time, in Andhra Pradesh: “The winter session of the Legislative Assembly began on stormy note on Monday, with members of the Telangana Rashtra Samiti, Telugu Desam and CPI (M) stalling the proceedings for an hour by staging a dharna at the podium, seeking a discussion on the Centre’s notification making it mandatory to print the skull and cross-bones sign on beedi bundles.”58 “Beedi bundles” refer to packets of cigarettes. Workers feared that they would lose their jobs if people realized that their product was deadly. The Opposition wanted to demonstrate their solidarity with the workers in an effort to solicit their support in future elections. • Demands for resignations of ministers function like demands for apologies, i.e., they are Opposition challenges to the power of the Government. An example is the “angry” Opposition’s call for the resignation of the Minister of Petroleum, Ram Naik, over the allotment of petrol pumps and LPG dealerships in August, 2002. The pandemonium resulted in the adjournment sine die of the Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha.59 • On August 25, 2002, in Karnataka, a former Minister of Social Welfare, H. Nagappa, was kidnapped by the brigand Veerappan and found dead on December 18 8 of that year. The issue was raised by the Opposition in the Legislative Assembly in a way that totally disrupted the body, leading to the suspension of MLAs, and, the security staff having to carry out recalcitrant members. An observer noted that the pandemonium was not so much an effort to find out what happened, rather, it was “the cold calculation of the ruling party’s opponents to draw political mileage out of this unmitigated human tragedy.”60 Gaining “political mileage” meant enhancing their power. • In the Uttaranchal Vidhan Sabha during March of 2005, dissidents within Congress forced repeated adjournments over the refusal of the government to discuss the forced resignation a couple of years ago of Revenue Minister Harak Singh Rawat on the grounds that it was sub judice. According to The Hindu, “Congress observers feel that the entire drama of forcing adjournments in the Assembly was being stage-managed by supporters of the State Congress president, Harish Rawat, who wanted to become Chief Minister by dislodging Narain Dutt Tiwari.”61 • The cessation of work caused by disruptions connoted a weakness on the part of Government. The Bharatiya Janata Party spokesman, V.K. Malhotra, started the debate saying that “apart from repeal of some legislation and a couple of Bills to replace ordinances, the Government has been unable to ready new legislation… Is this Government working, we wonder.” Two days ago, the BJP deputy leader in the Rajya Sabha, Sushma Swaraj, made a similar charge saying that on some days the Rajya Sabha was adjourned early for want of adequate business.62 • The battle for press coverage also is a battle for power: A “Mock Assembly” was organized by Telugu Desam Party MLAs who had been suspended from the LA. It was being televised and broadcast when the Chief Marshall Ashok Gajapathi Raju and his staff pulled out the cables and stopped the broadcasts. Members of the Media Advisory Committee and other journalists who met the Speaker pointed out that the ‘mock Assembly’ was being held at the ‘Media Point’, an area designated by the Speaker outside the main building for conducting television interviews and live telecasts since video cameras were barred inside. Mr. Suresh Reddy explained that he had neither ordered the ‘mock Assembly to stop nor prevented the live telecast initially in a spirit of democracy. But, members complained that some channels were showing only the mock and not the real Assembly. As this amounted to wrong use of the facility by the media, he had ordered the live telecast to be discontinued. He, however, assusred that the media would be allowed to work unhindered in the future.63 19 • Protests/agitations outside parliament tend to be used as surrogate measures of power. When a bandh is called, it is “graded” by observers as total or partial, indicating the relative power of the instigators. Similarly, when a disruption occurs in parliament, it is rated by the press according to whether it forces adjournment. If such disruptions can prevent the Government from acting then the disrupters have demonstrated their power. Political scientists tend to stress the centrality of the struggle for power over other possible causes. Often, the contention is made that alternative explanation are camouflage or rationalizations. Yet, as this brief review of six explanations for protest/agitation in India indicates, the interpretive task of determining the explanatory pre-eminence of one over the other is not as simple as simply accepting the perspective of one’s own discipline. IV. Assessment of the Explanations Each of the six explanations provided by observers has substantive merit. There is wide agreement among scholars that India is affected by a very high level of protest/agitation and this high level has become an accepted, and legitimate, part of India’s culture. Aspects of it are decried, but toleration is much greater than would be toleration in many other societies. Judging from the comments of many observers, there are limits to this toleration but they vary from place to place, individual to individual, situation to situation, and so on. Another way of saying the same thing might be to contend that there are sub-cultures in the country with varying levels of toleration for protest/agitation. It is apparent that many political leaders sense the limits, so that, for example, critical budget legislation will not be blocked by disruptions in legislatures. And, when protests/agitations become violent, most political leaders will decry their violence. A supporting culture does not provide an explanation for the spark which initiates protest/agitation or for the driving force that may be tapped by the protest/agitation—for that we must look elsewhere. A discontented population may be an essential requirement for protest/agitation, though the level of discontent and other circumstances that permit that discontent to be ignited are likely to vary greatly from situation to situation. Some years ago an associate was taking me around Hyderabad on his scooter and we were delayed by a protest that blocked all traffic. He posed a question: “Do you know why there are never protests by the same political party at the same time?” His answer was “because they have to hire the same people.” One would have to stretch the notion of “a discontented population” for it to be a requisite of such a protest. Yet, I doubt if “hiring” is a more significant engine for participation than discontent in most protests/agitations. The “Theory of Relative Deprivation of Elites of the Deprived,” proposed by Yasin and Dasgupta, directs attention to leaders who seem to be requisites of virtually all protests/agitations, but the narrowing of motivation of this group to power alone appears to simplify reality unreasonably. In legislatures, protests/agitations are undertaken by legislators. It is only reasonable that some are motivated by a desire for greater power within their parties or in other arenas. Outside legislatures, similar motivations may drive 20 some but to attribute to insincerity and selfishness the only motivations and/or the motivations of all is unreasonable. Likewise, the claim that the increase in the number of legislators who have criminal backgrounds can be said to be the cause of parliamentary disruptions is to confuse correlation and causation. The level of education of members of the Lok Sabha has risen with the din in that body. It would be a similar confusion between correlation and causation to attribute the disruptions to the “criminalization” of legislators and to attribute it to their increasing education. Like most of the other explanations, that which accounts for protest/agitation in terms of the failure of alternative means, including institutions like the courts and the media, may capture accurately some of the Indian reality. The presence of both a “Third World” and a “First World” in one country is bound to raise expectations among those living in the former beyond what the social and political institutions can deliver. The gap on a variety of measures between segments of the population in older democracies is less than that in newer democracies. The failure to deliver might reasonably result in the use of different tools than those that seem to perpetuate a status quo. Much of the protest/agitation comes from those who are not among those at the low end of the gap. Suicide and other mechanisms may be responses to the frustrations of a political system that does not improve livelihood sufficiently fast. And, since most protests/agitations lead to frustration, too, one might expect alienation from that means, too. Protest/agitation may be interpreted as symbolic or non-verbal communication, though it may be accompanied by loud noise. That is, the actions may be interpreted as equivalent to words. Indeed, most are justified by a political objective. Leaders interpret them as “saying” something, as a mode of expression. They tend to portray the actions as a more meaningful expression of the popular will than the simple words in a parliamentary debate. What is being “said” by protests/agitations requires interpretation. Actions may combine many messages. In the process of deciphering meaning, misrepresentation may occur. Nevertheless, participation in protest/agitation may be motivated by a sense that such action was, in the context of India, a means of expressing the wishes of the people. That the sole motivation of leaders, whether they be legislators, party leaders or leaders of other organizations, is power seems too simplistic an explanation to accurately reflect reality. That leaders might fool so many followers time and time again into thinking that the protests/agitations in which they were involved were for something that they were not seems unlikely. That power was the sole reason motivating leaders to carry out protests/agitations is similarly unreasonable. Mixed motives are common in driving people to action. That altruism is never one of these spurs to action is a criticism of Indian leaders that seems unfair. None of these explanations of protest/agitation leads by itself to a satisfactory accounting of the phenomena for which they claim to account. All seem to account for aspects of the reality, but a very complete explanation requires a much more complex accounting. 21 V. Conclusion The question we have sought to answer in this paper is “Why is not political discourse in India simply through words?” It is true that politics in no country is conducted simply through verbal exchanges. In India, though, active political protest and agitation, both outside and inside legislatures, constitute a much more significant proportion of political discourse than they do in any other democracy. To answer the question, we have examined a range of explanations for protest/agitation in India. Our conclusion is that none of the explanations adequately answers the question, though each seems to address an aspect of it. The challenge an observer of Indian politics faces is to determine the immensely complex mix of meanings conveyed by the myriad of protests and agitations which characterize the Indian legislatures and countryside. These protests/agitations speak in a language that is difficult to decipher. Each of the explanations we have reviewed provides hints about how they might be translated into words, but each is too general to provide a very accurate accounting of their meaning. That they are political expressions can not be denied. Interpreting their meaning will require a kind of contextual evaluation that is likely to defy generalization. Seeking to understand the language of protest and agitation will be an unending task—much like that of understanding the broad progression of politics in India. W.H. Morris-Jones wrote more than 35 years ago that the “modern language” of politics in India is the language of the Indian Constitution and the courts; of parliamentary debate; of the higher administration; of the upper levels of all the main political parties; of the entire English Press and much of the Indian language Press. It is a language which speaks of policies and interests, programmes and plans. It expresses itself in arguments and representations, discussions and demonstrations, deliberations and decisions.64 The challenge to understand politics is much like the challenge to understand the meaning of protest and agitation today. 22 Endnotes Note: The dates for some of the sources accessed on the internet precede the dates of the sources themselves. The reason is the time difference between California, where the sources were accessed, and India, where the sources were published. 1 Marcus Dam, “Confrontations Must Not Spill into House: Somnath,” The Hindu, November 28, 2004. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2004/11/28/stories/2004112802931000.htm Accessed November 28, 2004. 2 The term “protest/agitation” refers to a wide variety of actions taken by individuals and/or groups to dramatize a concern usually by disruption of the normal processes in society, such as by blocking traffic on a road or rail line, or in its institutions, such by interrupting the work of legislative bodies. Mohammad Yasin and Srinanda Dasgupta include in a list of protest techniques “…small public meetings, leaf letting, postering, submitting memorandum, press conference, press statements, mobile announcements, street corner meetings, long marches on foot, holding meeting at public places, mass rallies, processions, celebrating protest days, political drama, mass deputation, torch light procession, demonstrations, hartals, strikes, picketing, satyagraha, dharna, fasting including chair fast, fast unto death, sympathetic fast, selfimmolation, destruction of public property, holding up of transport, uprooting of railway tracks, damaging of control boxes, dislocating telephone and telegraph wires, burning of police stations and other government buildings, disturbing the public meetings of the opponents, go slow, mass casual leave, sit in demonstrations, looting pf public and private property, riot, localized attempts to throw off state authority and run parallel administration, declared or undeclared warfare in a region, etc.” And, they define protest “as those collective actions—legal and/or illegal, violent and/or non-violent—which seek to bring about a desired state of affairs either by bringing about change or resisting any change in the existing order.” See Mohammad Yasin and Srinanda Dasgupta, Indian Politics, Protests and Movements (New Delhi: Anmol Publications, 2003), pp. 8- 9. 3 Marion Weiner, “The Indian Paradox: Violent Social Conflict and Democratic Politics,” a paper presented at the International Colloquium on ‘Democracy and Modernity’ on the occasion of David Ben Gurion’s hundredth birthday, January 4-6, 1987, Jerusalem, published in Ashutosh Varshney, ed., The Indian Paradox, Essays in Indian Politics (New Delhi: Sage Publications, 1989), pp. 21-37. 4 Marion Weiner, “The Indian Paradox: Violent Social Conflict and Democratic Politics,” a paper presented at the International Colloquium on ‘Democracy and Modernity’ on the occasion of David Ben Gurion’s hundredth birthday, January 4-6, 1987, Jerusalem, published in Ashutosh Varshney, ed., The Indian Paradox, Essays in Indian Politics (New Delhi: Sage Publications, 1989), pp. 33-34. 5 A.R. Desai, “‘Public Protest’ and Parliamentary Democracy,” in S.P. Aiyar and R. Srinivasan, eds., Studies in Indian Democracy (Bombay: Allied Publishers, 1965), p. 299. 6 Editors, “A Disturbing Tend,” The Hindu, August 14, 2002. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2002/08/14/stories/2002081400061000.htm Accessed August 13, 2002. 7 Roy Mathew, “Declining Importance of Assembly,” The Hindu, August 5, 2002. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2002/08/05/stories/2002080502760400.htm Accessed August 4, 2002. 8 Roy Mathew, “Declining Importance of Assembly,” The Hindu, August 5, 2002. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2002/08/05/stories/2002080502760400.htm Accessed August 4, 2002. 9 “DMK Will Keep Off Session if Suspensions are not Revoked,” The Hindu, April 9, 2003. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2003/04/09/stories/2003040904730400.htm Accessed April 8, 2003. 10 “DMK Will Keep Off Session if Suspensions are not Revoked,” The Hindu, April 9, 2003. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2003/04/09/stories/2003040904730400.htm Accessed April 8, 2003. 23 11 “Opposition MLAs Evicted En Masse, Arrested,” The Hindu, April 11, 2003. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2003/04/11/stories/2003041105040400.htm Accessed April 10, 2003. 12 “Opposition MLAs Evicted En Masse, Arrested,” The Hindu, April 11, 2003. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2003/04/11/stories/2003041105040400.htm Accessed April 10, 2003. 13 “Protests Rock Parliament,” The Statesman, March 2, 2006. URL: http://www.thestatesman.net/page.arcview.php?clid=2&id=136267&date=2006-03-03&usrsess=1 Accessed March 2, 2006. 14 “Furore in Assembly Over Visakhapatnam Bypoll,” The Hindu, March 2, 2006. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2006/0302/stories/2006030209210100.htm Accessed March 1, 2006. 15 David H. Bayley, The Police and Political Development in India (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), pp. 258-259. 16 J. Prabash, “Where are the Giants?” The New Sunday Express, May 22, 2005. URL: http://www.newindpress.com/sunday/sundayitems.asp?id=SEV20050520045522&eTitle=Focus&rLink=0 Accessed March 3, 2007. 17 Mohammad Yasin and Srinanda Dasgupta, Indian Politics, Protests and Movements (New Delhi: Anmol Publications, 2003), p. 130. 18 Inder Malhotra, “Is Stoppage of Parliament the Only Answer?” The Hindu, August 29, 2004. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2004/08/29/stories/2004082904241000.htm Accessed August 31, 2004. 19 Inder Malhotra, “Is Stoppage of Parliament the Only Answer?” The Hindu, August 29, 2004. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2004/08/29/stories/2004082904241000.htm Accessed August 31, 2004 20 Inder Malhotra, “Is Stoppage of Parliament the Only Answer?” The Hindu, August 29, 2004. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2004/08/29/stories/2004082904241000.htm Accessed August 31, 2004 21 “Sign of Sanity,” Deccan Herald, July 12, 2004. URL: http://www.deccanherald.com/deccanherald/july122004/edit1.asp Accessed July 11, 2004. 22 “Sign of Sanity,” Deccan Herald, July 12, 2004. URL: http://www.deccanherald.com/deccanherald/july122004/edit1.asp Accessed July 11, 2004. 23 “Parliament in Tumult on Day Four Too,” The Hindu, March 5, 2005. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2005/03/05/stories/2005030508531100.htm Accessed March 4, 2005. 24 Sajma Heptulla, “Address,” in G.C. Malhortra, ed., Discipline and Decorum in Parliament and State Legislatures, All-India Conference of Presiding Officers, Chief Ministers, Ministers of Parliamentary Affairs, Leaders and Whips of Parties, New Delhi, 25 November 2001 (New Delhi: Lok Sabha Secretariat, 2003), p. 28. 25 G.M.C. Balayogi, “Welcome Address,” in G.C. Malhortra, ed., Discipline and Decorum in Parliament and State Legislatures, All-India Conference of Presiding Officers, Chief Ministers, Ministers of Parliamentary Affairs, Leaders and Whips of Parties, New Delhi, 25 November 2001 (New Delhi: Lok Sabha Secretariat, 2003), p. 11. 26 Atal Bihari Vajpayee, “Address,” in G.C. Malhortra, ed., Discipline and Decorum in Parliament and State Legislatures, All-India Conference of Presiding Officers, Chief Ministers, Ministers of Parliamentary 24 Affairs, Leaders and Whips of Parties, New Delhi, 25 November 2001 (New Delhi: Lok Sabha Secretariat, 2003), p. 14. 27 Krishan Kant, “Inaugural Address,” in G.C. Malhortra, ed., Discipline and Decorum in Parliament and State Legislatures, All-India Conference of Presiding Officers, Chief Ministers, Ministers of Parliamentary Affairs, Leaders and Whips of Parties, New Delhi, 25 November 2001 (New Delhi: Lok Sabha Secretariat, 2003), p. 18. 28 Leslie J. Calman, Protest in Democratic India, Authority’s Response to Challenge (Boulder: Westview Press, 1985), p. 13. 29 David H. Bayley, The Police and Political Development in India (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), pp. 258-259. 30 Leslie J. Calman, Protest in Democratic India, Authority’s Response to Challenge (Boulder: Westview Press, 1985), p. 237. 31 Suman Kwatra, Satyagraha and Social Change (New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications, 2001), p. xii and, also, p. 3. 32 David Cortright, Gandhi and Beyond, Nonviolence for an Age of Terrorism (Boulder: Paradigm Publishers, 2006), p. 22. 33 Suman Kwatra, Satyagraha and Social Change (New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications, 2001), pp. viiviii. 34 Mohammad Yasin and Srinanda Dasgupta, Indian Politics, Protests and Movements (New Delhi: Anmol Publications, 2003), p. 14. 35 A.R. Desai, “‘Public Protest’ and Parliamentary Democracy,” in S.P. Aiyar and R. Srinivasan, eds., Studies in Indian Democracy (Bombay: Allied Publishers, 1965), p. 317. 36 A.R. Desai, “‘Public Protest’ and Parliamentary Democracy,” in S.P. Aiyar and R. Srinivasan, eds., Studies in Indian Democracy (Bombay: Allied Publishers, 1965), p. 310. 37 A.R. Desai, “‘Public Protest’ and Parliamentary Democracy,” in S.P. Aiyar and R. Srinivasan, eds., Studies in Indian Democracy (Bombay: Allied Publishers, 1965), p. 323. 38 Mohammad Yasin and Srinanda Dasgupta, Indian Politics, Protests and Movements (New Delhi: Anmol Publications, 2003), p. 180. 39 S. Viswam, “The Decline in House Norms,” Deccan Chronicle on the Web, July 8, 2004. URL: http://www.decan.com/Columnists/Columnists.asp Accessed July 7, 2004. 40 Ghanshyam Shah, Protest Movements in Two Indian States, A Study of the Gujarat and Bihar Movements (Delhi: Ajanta Publications, 1977), p. 10. 41 Ghanshyam Shah, Protest Movements in Two Indian States, A Study of the Gujarat and Bihar Movements (Delhi: Ajanta Publications, 1977), pp. 29-30. 42 Leslie J. Calman, Protest in Democratic India, Authority’s Response to Challenge (Boulder: Westview Press, 1985), p. 235. 43 Harish Khare, “Reclaiming the Power of Disapproval,” The Hindu, March 15, 2007. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2007/03/15/stories/2007031503651000.htm Accessed March 14, 2007 25 44 Editors, “Parliament Live,” The Hindu, December 11, 2004. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2004/12/11/storoies/2004121101301000.htm Accessed December 10, 2004. 45 Harish Khare, “Reclaiming the Power of Disapproval,” The Hindu, March 15, 2007. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2007/03/15/stories/2007031503651000.htm Accessed March 14, 2007. 46 Mani Shankar Aiyar, “Making Parliament More Meaningful,” The Telegraph, n.d. URL: http://www.telegraphindia.com/1000829/editoria.htm Accessed March 3, 2007. 47 Ghanshyam Shah, Protest Movements in Two Indian States, A Study of the Gujarat and Bihar Movements (Delhi: Ajanta Publications, 1977), p. 3. 48 David H. Bayley, “The Pedagogy of Democracy: Coercive Public Protest in India,” The American Political Science Review, Vol. 56, No. 3 (September 1962), p. 663. 49 David H. Bayley, The Police and Political Development in India (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), p. 275. 50 David H. Bayley, The Police and Political Development in India (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), p. 275. 51 Leslie J. Calman, Protest in Democratic India, Authority’s Response to Challenge (Boulder: Westview Press, 1985), p. 11. 52 Pavan K. Varma, Being Indian, The truth about why the 21st century will be India’s (New Delhi: Penguin, 2004), p. 43. 53 Pavan K. Varma, Being Indian, The truth about why the 21st century will be India’s (New Delhi: Penguin, 2004), p. 54. 54 Mohammad Yasin and Srinanda Dasgupta, Indian Politics, Protests and Movements (New Delhi: Anmol Publications, 2003), pp. 11-12. 55 Mohammad Yasin and Srinanda Dasgupta, Indian Politics, Protests and Movements (New Delhi: Anmol Publications, 2003), p. 180. 56 Mohammad Yasin and Srinanda Dasgupta, Indian Politics, Protests and Movements (New Delhi: Anmol Publications, 2003), pp. 14-15. 57 “BJP Stops House Again,” Deccan Chronicle on the Web, December 12, 2006. URL: http://www.deccan.com/home/homedetails.asp#BJP%20stops%20House%20again Accessed December 11, 2006. 58 “Stormy Start to Winter Session,” The Hindu, December 12, 2006. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2006/12/12/stories/2006121209460400.htm Accessed December 11, 2006. 59 Editors, “A Disturbing Tend,” The Hindu, August 14, 2002. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2002/08/14/stories/2002081400061000.htm Accessed August 13, 2002. 60 N.C. Gundu Rao, “Unruly Conduct of Legislators Dwarfs Democratic Decorum,” Deccan Herald, December 31, 2002. URL: http://www.decccanherald.com/deccanherald/dec31/top.asp Accessed December 30, 2002. 26 61 “Ruling MLAs Force Uttaranchal Assembly Adjournment,” The Hindu, March 23, 2005. URL: http://www.theshindu.com/2005/03/23/stories/2005032303950500.htm Accessed March 22, 2005. 62 Neena Vyas, “Opposition, Government Trade Charges Over Legislative Business,” The Hindu, December 11, 2004. http://www.thehindu.com/2004/12/11/storoies/2004121101301000.htm Accessed December 10, 2004. 63 “Mediapersons Lodge Protest with Speaker,” The Hindu, March 24, 2006. URL: http://www.thehindu.com/2006/03/24/stories/2006032412390400.htm Accessed March 23, 2006. 64 W.H. Morris-Jones, The Government and Politics of India (London: Hutchinson University Library, 1971), p. 54. 27