Memory for Pictures: A Life-Span Study Kathy Pezdek

advertisement

Memory for Pictures: A Life-Span Study

of the Role of Visual Detail

Kathy Pezdek

The Chremont Graduate School

PEZDEK, KATHY. Memory for Pictures: A Life-Span Study of the Role of Visual Detail. CHILD

DEVELOPMENT, 1987, 58, 807-815. This experiment assessed the effect of the amount of physical

detail in pictures on picture recognition memory for 7-year-olds, 9-year-olds, young adults, and older

adults over 68. Subjects were presented simple and complex line dxawings, tactorially combined in

a "same-different" recognition test with simple or complex forms of each. For each age group,

recognition accuracy was significantly higher for pictures presented in the simple dian in the

complex form. This eflfect was due to diflferences between simple and complex pictures in the

correct rejection rate but not die hit rate; subjects were less accurate detecting deletions fix>m

changed complex pictures than addithns to changed simple picitures. The older adults were no

better than chance at correctly rejecting changed complex pictures. Altfiou^ increasing the presentation duration from 5 sec to 15 sec increased overall accuracy, it did not increase subjects' ability to

correctly reject changed complex pictures. Results are interpreted in terms of schematic encoding

and storage of pictures. Accordingly, visual information that communicates the central schema of

each picture is more likely to be encoded and retained in memory than information diat does not

communicate this schema.

Individuals have an impressive ability to

remember pictures they have seen before.

This has been demonstrated with recognition

tests (Nickerson, 1965; Shepard, 1967; Standing, Conezio, & Haber, 1970) as well as with

recall tests (Bousfield, Esterson, & Whitmarsh, 1957). In addition, a number of developmental studies have reported increases

with age, from childhood to early adulthood,

in recognition memory for large nxmibers of

pictures (Hofi&nan & Dick, 1976), recall and

recognition for visual objects (Dirks &c Neisser, 1977; Mandler, Seegmiller, 6E Day, 1977),

and face-reex)gnition memory (Blaney fie

Winograd, 1978). However, few of these studies have examined qualitative developmental differences in picture memory. In other

words, are adults and older chilciren processing pictures differently than younger children, or are they just performing the same

processes better?

In typical picture recognition memory

studies, subjects are presented a series of pictures to remember and are then presented a

test that includes some of die "old" pictures

and some "new," distractor pictures. In the

large majority of these studies, the "new,"

distractor pictures are completely new pic-

tures. This procedure thus tests how well subjects can distinguish pictures they have seen

from picjtures they have not seen, and they

can do this quite well. What we do not leam

from these studies, however, is how much of

the visual detail in a pic^ture has been retained in memory when a picture is recognized. The present study examines this particular aspect of picture memory and tests for

qualitative differences in these processes

with age.

We initially addressed this issue in an

earlier study from our laboratory (Pezdek &

Chen, 1982). In this previous study, 7-yearolds, 9-year-olds, and young adults were presented simple and complex line elrawings of

scenes. The simple and cK)mpIex forms of

each picture contained the same c^entral information, but peripheral details, shading, and

embellishment were added in the complex

form of each pic^re. These pictures were selected from the set of pictures utilized by Nelson, Metzler, and Reed (1974) and originally

constructed by Nickerson (1965). At test, pictures were presented one at a time in a

"same-different" recognition test Half of the

simple and complex line elrawings were

tested in the same form as presentation; half

This research was conducted while die author was supported by a grant from the National

Institute of Education. I especially thank Sidney Fox for collecting the data for diis study and Tom

Dougherty fbr analyzing the data, and I appreciate conceptual contributions and feedback on die

manuscript provided by Ruth Maki. Requests for reprints should be sent to Kathy Pezdek, Department of Psychology, The Claremont Craduate School, Claremont, CA 91711.

[Child Development, 1987,58, 807-815. © 1987 by tfie Society for Research in Child Etevelopment, Inc.

All rights reserved. 0009.3920/87/5803-000S$01.00]

808

d f l d Development

were changed picUires. The changed test pic- 1969; Tverricy & Shrarman, 1975) as w ^ as for

tures were arrived at by chan^s^ tiie pictures &ces (Lffi^«y, Alexander, & Lane, 1971)

that had been presented in a simple form to increases w£th preseHiitation time and tfut ike

tiie complex form of tibe same picture and beneSts of incireased presenl^fm tlo^ are

changing pictures that had been presented in greater for yovrag c ^ & e n Aao for older c ^ a complex form to tiie simple form of tiie same dren and acblts ( H B ^ Mcairison, & Sheingold, 1970; Naus, Omstein, & Mvano, 1977;

picture.

Pezdefc & Mlceli, 19^). Seven-year-olds and

The piincipal result of Pe2Kiek and Chen 9->^a'"0lds were included in the pre^nt

(1982) was tbat for adults, recx^Eiitlon sen- study for cOTi^Mn^^ay wifli the P e z d ^ and

sitivity, meastcred in terms of d', was grei^r Chen (19^) stucb' and, al«), bec»ise previd&

^

l

for pictures in tiie simple than in tiuf C(^

preseirtation condition. However, for 7-i

olds and 9-yeaiHklds, recxignltion sensUJ , . f^E»Uy scun pk^uw

measured in temis of d', was similiB- for pic- cale atl^tlcm to central versus

tures in the ^ns^effiEidccm^^fix p^es^rarttttion cJbbOls (see Goo^ban, 1S80;

condition. 'Hus finding is in maslced cffliferast & Bruner, 1970; V « « | ^ t , 19

to Reese's (1970) hypothesis tiiat reteatitm of & present study ioduded a

visual stimi^ should be posi^vdy rektedl to

l k , haa^ on recent &

the amount (^ dBtf^ in &e ^mali. It is ako

also b e o ^ more Aan

inconsistent witii studies that have repeated ger adiiAs &(»Q iacrettsed Tgs^Beao^0^im

superior recall for compl«£ over simple pic- on meoHiry t a ^ (Cza& & BiS^nowUz, 1985;

tures (Bevan & Steger, 1971; Evertson & Wingfield, Pooa, Unnbrnxli, & Lowe, 1965).

Wicker, 1974) or no difierence between

aduhs* recognition ctf uix^le and comidex^clife span were u ^ s e d in Ms s t e ^ to test if

tures (Nelson et al., 1974).

dS

hiomn to ^dst in

on the above s p ^ S ^ cliSf^Qces between

the test items used by P e a ^ and Oran and

those used in odi» studies. That is, Pe^ek

and Chen utilized test |^c;tures v/iHk &e same

centxal iafom^rtion as i^ctiues presented, but

with added or deleted elabor^ve viswil det ^ s . This study thus speeifically tested memory for the visual di^ails in pfctaires thai retained the same thematic ctmtwat in their

simple and comi^^ forms. Aj^paready, ^ten,

faults' ability to cSiscrimuof^ same &om

changed simple pictures is gr^^a: 6utQ their

ability to discriminate swne feom

r— r—--—.

*•

1.

J

to discrinikiate same nom c^bai^ed plcte^es

was similar for simile wid conqcHex jrfctures.

The puipose of tiie present study was to

farther p r c ^ the quiaiiidive deferences between Euhilts and c^dren in recc^p^tion

memory for visual deteils in pU±iu%s. This

study tested tiie hypt^esis ti^ tbe e^ differences reported by PezcJ^ and CSien (1982)

could be accounted for by cHififei'raices in tiie

time required to encode and (nocess infomiation at dififerent ages. That is, at a given presei^^lon dimrtion, it is hypoi^esisMMi tiiat

c^iikben ce^^xae less of the aviidJtiMe vbual

detEols in memory tiian do yoiuig adi^ts* and

tiius tiieir memory perfiMmimce is simile

with simple and complex pictures.

It has been demonstrated that memory

fbr pictures (Potter, 1976; Potter & Levy,

pictures.

In tiie present study. 7-year-old8,9-yearadMte (coAei^ stadente), toid

jprocedkire c^ized hy Pezeiek md Chen

~), w ^ iHesectation time per ^ d u r e

.

.jen sd:^oete. Tbe |H»lHg#*UHi

ut^xdhy

P e z M and C&en ( I M ) was

8 sec per pctuie. In the iseBcait ^&^, each

picture was pvescmUtd for 5 (»• 15 sec. If the

3es in i8co®^tion taemnixy for

jf^^alev^ctiu:^ lepotted^ Pezand C3ien Jl^Z) are in paA chie to age

v«««erences intbe speedof ei«x»lte®U!fiMana^^^^ ^ ^ ^ mwii^l^faaiE pn^ntttttbn ^Eoe in

^^ present ^udy ^ouM resiA in s u u i ^ pattems erf r e s i ^ among age ffotps ^

^

slower pres^rtOtJon time but not at tiie faster

S v i ^ e c t s . — V c a t y sufcg

p ^ ^

each <kfourage gtoi^ps. Seven-yeotKiids (M

= 6.8 years, SD = .23) and 9-year-olds (M =

8.9 years, SD = .35) partirafeaibed 6om public elimm^m schools in Otu^srant, Ci^for•ia, a mklc&Hdb^ subuib in L(» Angela

Gounty. tlie yoimg a&Ut suli^iects were

uMie^gmdiii^s vfho vokmteesedfrcnnclasses

at tile CUrenHmt CdBeges (M = 21.5 yeais,

SD - 5.44). Tlie dder a d t ^ were volunteers

from a retirement community in Claremont.

Kathy Pezdek

809

They ranged in age from 68 to 90 (M = 80.2

years, SD = 4.52), were generally well

educated (M = 17.4 years of education, SD =

3.4), and were amply healthy to live selfsufiiciently. In each age group approximately

equal numbers of males and females participated in each condition, but gender was not

si)ecifically controlled for.

sentation pictures. The 11 changed versions

of simple presentation pictures were tiie

complex versions of these pic:tures. The 11

changed versions of the complex presentation pic^res were the simple versions of

these pictures. Thus, each of tiie 44 presentation pic*ires was included onc« in the test

phase, in eitiiar the same or changed form.

Design.—All subjects viewed simple and

complex line drawings in the presentation

phase and were tested with same and

changed forms of these pictures. Twenty subjects in each age group were presented the

pictures at a duration of 5 sec each, and 20

were presented the pictures at a duration of

15 sec each. The study can thus be described

a s a 4 x 2 x 2 x 2 mixed &ctorial design

with age and presentation duration as between-subjects factors and presentation form

and test form as within-subjects Victors.

In the tBSt phase, subjects viewed pictures one at a time at a rate controlled by tiie

experimenter. For each pic;ture the experimenter asked, "Is this picture the same as a

picture you saw before, or are there some

changes in this picture?" Several practice

slides were shown first to ensure that subjects

understood what types of changes c:onstituted

changed test items. The assignment of each

picture to conditions of presentation and test

and the sequencing of presentation and test

slides were arranged in two orders. Half of

the subjects in each condition were randomly

assigned to each order. A 3-min intervening

delay task (circling all of the twos on a random number sheet) was included between

presentation and test to ensure that the test

that followed measured long-term memoiy.

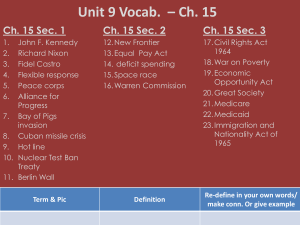

Materials.—The materials were the same

as those used by Pezdek and Chen (1982) and

were selected from the set of pictures used by

Nelson et al. (1974) and, originally, by Nickerson (1965). These included 44 basic pictures,

each drawn in both a simple, unembellished

line drawing form, and a cx)mplex, embellished line chawing form, for a t o ^ of 88 pictures. All drawings were black and white.

The complex form of each picture was an exac^ reproduction of the simple form, with the

adciition of elaborative details to both the

principal figure and the background. The central information was thus the same in the simple and complex form of each picture. Examples of stimulus pictures are shown in Figure

1. The use of the same materials as in previous studies strengtiiens this study by allowing

a comparison of results ac^ross studies without possible confounding effects of different

materials.

Procedure.—Subjects participated individually. They were presented a sequence of

slides including 44 presentation pictures, followed by a 3-min delay task, and then 44 test

pictures. The presentation pictures included

22 simple line drawings and 22 complex line

drawings. In the presentation phase, subjects

were instruc!ted to study each picture carefully, as it would be important in a later part

of die experiment The pic;tures were presented on slides by a Kodak Carousel slide

projector. During the presentation phase,

slides were presented for 5 sec each or for 15

sec each. The inter-slide interval was 1 sec.

The test sequence consisted of 22 pictures from the presentation phase—11 simple

and 11 complex pic^tures. The remaining 22

test pictures were c^hanged versions of pre-

Results

The data were scared and analyzed in

terms of the mean percent correct as well as

the signal detection measure of d'. However,

the m^jor results of this study concem di£Ferences between the percent correct data for

same test items (i.e., tiie hit rate) and changed

test items (i.e., the csoirect rejection rate).

These two conditions cannot be examined

separately with the d' measure. Throu^out

the study, results are considered significant at

tile .05 level.

OveraU results.—A 4 (age) x 2 (presentetion duration) x 2 (simple or complex presentation form) X 2 (same or changed test

form) mixed factorial analysis of variance was

performed on the percent correct data. All

main effects were significant First, there

were signific^ant difierencies among the four

£^e groups; young adults perfonned best

(83.2%), followed by ^year-olds (75.4%), 7year-olds (67.6%). and older adults (67.0%),

F(3,152) = 29.94, MS^ = 309.10. Tukey pairwise compariscms indic^ated that only the differences between young adulte and 7-yearolds and between young adults and older

adtilts were significant Recognition acxnuacy

was higher at the l5-sec rate (76.4%) than at

the 5-sec rate (70.2%). F(l,152) = 20.04, MSe

= 309.10. Sulgects were more accurate recognizing pic^res in the simple (79.5%) than

cx)mplex (67.2%) presentation form, F(l,152)

= 100.71, MSe = 240.39, and they were more

810

Child Development

SIMPLE

COMPLEX

FIC. 1.—Examples of pictures in both simple and complex form

accurate recognizing pictures tested in the

same form (hit rate = 77.9%) than in the

changed forni (correct rejection rate =

68.7%), F(l,152) = 32.62, MS^ = 240.39.

Interpretations of these main effects are

qualified by three significant interactions.

First, as can be seen in the bottom row of

Table 1, the interaction of presentation form

X test form was significant, F(l,152) = 32.31,

MSe = 161.49. Post hex: comparisons revealed

that the hit rate did not differ between pictures presented in the simple form (81.3%)

and complex form (74.7%). However, the correct rejection rate was significantly less for

pictures presented in the complex form

(59.7%) than for pictures presented in the

simple form (77.7%), i(152) = 1.81. In other

words, subjects were significantly less accurate at detecting deletions from changed complex pictures than they were at detecting additions to changed simple pictures. This

pattem of results was also the basis for the;

significant main effect of presentation form on

d'data,F(l,152) = 70.29, MS^ = 1.02, with d'

greater for simple (d' = 2.12) than for complex pictures (d' = 1.17).

The interaction of presentation form x

test form on percent correct also entered into

significant second-order interactions of age x

presentation form x test form, F(3,152) =

10.22, MSe = 161.49, and presentation duration X presentation form X test fonn.

Kathy Pezdek

811

TABLE 1

MEAN PERCENTAGE CORRECT IN EACH EXPERIMENTAL CONDITION

PRESENTATION CONDITION

Complex

Simple

TEST CONDITION

7-year-olds:

5 sec

15 sec

Mean

9-year-olds:

5 sec

15 sec

Mean

Young adults:

5 sec

15 sec

Mean

Older adults:

5 sec

15 sec

Mean

Overall mean

Same

Changed

Same

Changed

71.4

82.7

77.0

61.4

74.5

67.9

60.5

69.1

64.8

64.5

56.8

60.7

80.4

90.9

85.7

76.8

80.9

78.9

72.7

80.9

76.8

62.3

58.2

60.2

83.6

87.7

85.7

87.3

91.8

89.5

80.0

88.6

84.3

71.8

74.5

73.2

73.6

79.5

76.6

81.3

68.6

80.0

74.3

77.7

68.2

77.3

72.7

74.7

40.0

49.1

44.5

59.7

F(l,152) = 4.99, MSe = 161.49. However, tiie

overall age x presentation duration x presentation form X test form interacrtion did not

approach significance (F< 1.00).

The signific^ant interaction of age x presentation form X test form is of particnilar interest because this interaction allows an assessment of qualitative differences in picture

recognition memory with age. These results

are presented in Table 1. In order to assess

the nature of this interaction, separate 2 (presentation form) X 2 (test form) analyses of

variance were performed on the data for each

age group. The presentation form X test form

interaction was significant for each age group

except 7-year-olds. Further, for each age

group except 7-year-oIds the difference between the hit rates for simple and complex

pictures was not significiant; however, the correct rejection rate was significantly less for

changed c^omplex pictures than for changed

simple pic^res. On the other hand, for

7-year-olds, although pic^tures presented in

their simple form were recognized significantly more accurately than pictures presented in their complex form, F(l,38) =

12.08, the test form x presentation form interaction was not significant.

In order to assess the nature of the significant interaction of presentation duration x

presentation form x test form, separate 2

(presentation form) x 2 (test form) analyses of

variance were periformed on the data at each

presentation duration. The presentation form

X test form interaction was significant at htiAi

presentation rates. Further, the percent correct difference between the 5-sec and 15-sec

conditions was significant in all cx)nditions except for changed complex pictures. The correct rejection rats fbr complex pic:tures was

exactly the same (59.7%) at both presentation

durations. Thus, increasing the presentation

duration by threefold did not increase subjects' ability to detect the deleted details in

pictures that had been presented in the complex form.

Comparisons of young and older adults

only.—Several previous studies have reported tiiat differences in memory performance between young and older adults can in

part be acxiounted for by age differences in

pDDcessing time (Craik 6c Rabinowitz, 1985;

Wingfield et al., 1985). The older adults were

included in the present study to examine

qualitative ciifferences in memory for details

in pictures between tiiese two age groups

and, specific^ally, to probe whetiier age differences in processing time underlie these memory differences. Furtiier. the significant age X

presentation form x test fonn interaction reported above statistically justifies examining

these two age groups separately.

A 2 (age) x 2 (presentation duration) x 2

(presentation form) x 2 (test form) mixed factorial analysis of variance was performed on

the percent correct data. All main effects

812

were significant in tiie same direction as in

the overall axisAysis reported above. Of particular interest is tiie finding thiA recogmtion accuracy was higher for yoimg adults (83J2%)

tiian for older aduhs (67.0%), F(l,76) = 74.89,

MSe = 278.17. There were also signlficfuit interactions of age X presentE^on form, F(l,76)

= 5.27, MSe = 240.13, age x test form,

F(l,76) = 7.71, MSe = 348.J®, and presentation fctrm X test form, F(l,76) = 55.59, MS^

= 150.51. Interpretations of each of these

firstKJrder interactions are qualified by the

significant secx}nd-orc^r interaction of £^e x

presentation form x test form, F(l,76) = 3.95,

MSe = 103.40. As can be seen in the bottom

half of Table 1, the hit rates for botii £^e

groups did not significantly differ between

simple and complex presentation pictures.

However, for botii age groups, the correct rejection rate was hi^ier for pictures pres^ted

in the simple form than in the complex fc»tn,

but the size of this dil&ren<% was almost

twice as laige for older adidts as for younger

adults. The older adults were, in foct, no

better than chance at detecting deletions in

changed complex pictures at both the 5-sec

and 15-sec presentfUion duratum. No iii*eracticms invcjving pxesenta/don rate ai^rcnac^ied

significance.

Toother, tiiese results su^^est tiuit there

are iKjtfi quantitB^ve and q u i ^ t ^ v e deferences between young and c^der »lults in

menwiy iox detfdls in pictures. However, tiie

absence t^ a significant iotenKition wi£b presentfrfion duration incUcates tiiat tiiese xHlferences are not singly a result of procjessing

rate differences between these two age

groups.

Disciuwion

This study examined develqcHnental differences in memory for details in pictores.

Across £dl four ^ e groups, psrtures presented

in their simj^e form were reco^ized mwe

accun^ly than pictim«s j^reseated in tiieir

complex form, liiis fincite^ c^lfers &cun results repented elsewhere wi^ recsall measures

(Bevm & Steger, 1971; Everlson & Wtdcer,

1974) as well as witii a recogniticm measure

using completely new picbiinss as d^iactor

items (Nelson et al., 1974). t h e results of tiie

present study suggest tiiat sul^ects axe more

accurate at Astinpii^U]^ srane hom duinged

simple pic;hires ti^ tiiey are at c^c»im&nf^ing same hom didnged com^^ex pictures.

Why is this the case?

One interpretation of these results is

based on previous findii^ t h ^ pictures, like

prose materials, are processed schematically

(see Friedman, 1979; Goodman, 1980; Nickerson & Adams, 197^). For example, consider

the chawing represented at the bottom left of

Figure 1. l l i e schema applied to tike |»cture

wcmld be the prepositional representation of a

sentence such as, "The clown is crying." Acc^txlin^y, infinmation that communict^s the

central Schema of each picbire is mcare lticely

to be ehcoded and retained in memory than

information tiiat does not communicate this

schema. It is important to note that tiie implication here is not that schemata are preserved

in memcffy in a verbal form but, rotiier, that

the pictorial ui&nrmatkat that is enc»>dbd schematkraily is stoaikz' to tiie type of in&sm^ion

that can be represented in a sentence tiiat summarizes the picture.

Relevant to the present study, it is suggested that the schema that is cilerived from

the simple wid the cc»nplex form of eaeh picture is e s ^ ^ ^ y the same aad corresponds

to the mfonn£^on in the simple fcaxn of efuh

picHwre. Thus, if subjects' memory repre^ntation fc»- both simpilb and cora^ilex pictures is

similar to the simple version of each picture,

they would be less accurate disciimiimtiQg

same from chwaged comt^ex pictures tiuin

discaimii^ing same firom clmiged simple

pictures.

Tlie next question, however, is how this

suie dtuatitHi in tiie present study. Ute results c^ the prese^ study, ^^etiser with those

of otiiers (see Potter, 1976; P<»ter & Levy,

1969; Tvetsky & Sherman, 1975), s u p ^ r t Ae

c»iu}lusion ^ak memory for pictures inciieases

as the exp<»ure dtmttton per ftfcture increases. The mterpretation of this effect offered in tire i^evious stucUes has been that

increased stiic^ tune leads to better niemory

singly because more in^cKmatkm about the

detidSs of tiie pic^ores is encodbd smd retuoed

at the loiiger inteiWls. However, only cme of

tile studies repo^q|! increased picture rec?ognition m«mo^ with sti*dy time (T^^tsky &

Sherman, WfSi) required subjects to cUstinguish staaefrconchss^ged test ^ctures, and in

tiua stady the rect^i^iiion dala wexe not analyzed separately for hits mid correct rejections. Ala>, in the presoat study, i d # ^ u ^ increasii^ tiie eiqposius duration from 5 sec to

15 sec increasoi overall picture recogititiion

accniracy, xeco^aitioD accuracy for changed

complex pictures was low and ex»ctiy the

sanw (59,7%) at b ( ^ pres^itii^n Orations,

llius, althot^^ increi^ing study tm^ does

lead to b^ter o\%rall pidhire recc^iUtion

ni«mc»y, tiieje is no suppaxt for the hypothesis t h ^ tiiis is simply because more de~

Kathy Pezdek

tails are encoded and retained at longer intervals.

In line with the schematic prcwessing notion outlined above, one interpretation of the

finding that pictures are better recognized at

longer study intervals is that this is due to

qualitative differences rather than quantitative differences in encx)ding and storage of

detail information. If we view picture memory as a schema-driven process, then with

longer on-time subjects would be able to bet'

ter abstract the central schema of each picture

and enrich the memory representation of the

schema by incorporating into it more of the

schema relevant infonnation in the picture.

This would result in better schemata in memory, not merely the storage of more details

from the picture.

There are a few other studies in which

recognition memory for additions to pictures

and deletions from pictures have been compared. However, each of those studies differs

in subtle but significant ways from the present study. In some studies, for example, subjects were instructed to respond "old" to original pictures and to changed original pictures,

and "new" only to completely new, distractor

pictures. Results of these studies are not relevant to the present interest in subject' ability

to distinguish original from changed pictures.

The study by Park, Puglisi, and Sovacool

(1984) is one snch study.

In a more relevant study, Mandler and

Ritchey (1977) presented college subjects

with eight line drawings, each containing six

objects. The recognition test that followed included 64 "old" pictures composed of the

eight target pictures plus seven transformations of each, and 64 completely "new" distractor pictures. The two transformations

relevant to the present discussion were (a)

additions and (b) deletions, in which a new

object was added to or deleted from a target

picture. They reported no significsmt loss over

4 months in the recognition of additions or

deletions (in the organized picture condition),

and recognition accuracy did not differ between these two types of pictures.

These Tesults differ from results reported

in the present study. However, there are two

important differences between these two

studies. First, in the Mandler and Ritchey

(1977) study, subjects were "correct" if they

classified either the target pic^res or the

transformed pictures as "old." Thus, their results do not allow us to assess how well subjects distinguished target pictures from transformed versions of these pic^res. Second,

813

additions and deletions in the Mandler and

Ritchey (1977) study involved adding or deleting a whole object in an array of objects.

Additions and deletions in the present study

involved adding or deleting more general

elaborative details in the simple and complex

version of each picture. Differences between

the results of these two studies c^an be accounted for by these methodological differences.

In another relevant study. Brown and

Campione (1972) had preschool children

study pictures from children's bcwiks. Two

hours, 1 day, or 7 days later they were presented completely new distrac:tor pictures,

identical original picrtures, and changed

original pictures. The changed version of

each original included the same character

(same clothes, same colors, etc.) as in the original picture but in a different pose. Subjects

responded "old" or "new" and tiien classified "old" items as either "identical" or

"changed."

Subjects weTe similarly accurate classifying original and changed pictures as "old" at

each of the three retention intervals. However, subjects were more accurate classifying changed pictures as "changed" than they

were classifying identical pictures as "identical." Although these findings differ from

those reported in the present study, they do

suggest that subjects are generally able to

"notice what is new" in changed old pictures.

The differences in results between the prt;sent study and that by Rrown and Campione

(1972) can be attributed to differences in the

type of changes included in "changed" test

pictures as well as to differences in the age of

the subjects.

Thus, several other studies have investigated memory for additions to and deletions

from pictures. None of these studies concurs

with the principal result of the present study,

that extra detail added to changed simple pictures is detected more accurately than detail

deleted from changed complex pictures. However, there are notable methodological differences between the present study and each of

these other studies.

There are two major developmental differences in the pattem of results in the present study. First, for 7-year-olds the (difference

in the correct rejection rate for pictures presented in the simple (67.9%) and complex

form (60.7%) was not statistically significant,

although this difference was significant for

each of the other three age groups. This

finding is consistent with the results of Pez-

814

Child Development

dek and Chen (1982) that differences among

the four means defined by conditions of presentation form and tost form were less for the

younger children than for the young adults.

This result is also in line with the above interpretation of the overall memory advantage for

simple over complex pic;tures. That is, if simple pictures are better retained than complex

pictures because of schematic processing of

the pictures, and if young children are less

likely than older children and adults to encode pictures schematically, then it would be

expected that the correct rejection rate difference between simple and complex pictures

would be less for younger children as well.

The second developmental difference in

the obtained pattern of results involves a comparison of the young and older adults. Although both young and older adults were

significantly more accurate rejecting changed

simple pictures than changed complex pictures, older adults were far less able than

young adults to correctly reject changed

complex pictures. In feet, older adults were

no better than chance at correctly rejecting

changed complex pictures.

According to the interpretation previcmsly outlined, these results suggest that

when older adults encode complex pictures,

they retain far less of the elaborative details

than do young adults. Thus, at the time of test,

their memory of complex pictures is similar to

the simple form of each picture, and they respond, "Same." Further, the fact that differences between the young adults and the older

adults did not result in significant interactions

with presentation duration suggests that the

processing differences between young and

older adults are not simply a result of processing rate differences.

This study leads to the conclusion that

although adults and children are extremely

accurate at discriminating old pictures from

completely new pictures (Hof&nan & Dick,

1976; Nickerson, 1965; Shepard, 1967; Standing et al., 1970), they are far less accurate discriminating same from changed versions of

old pictures, especially when the changes involve detecting what extra detail has been deleted from changed complex pictures. These

results are important because they suggest

that when we "remember" a picture or a real

world scene, we do not necessarily retain all,

or even most, of the elaborative detail presented. This is consistent with the notion that

pictures, like prose materials, are processed

schematically. As such, scheme-relevant

information in pic:tures is likely to be retained

well in memory, whereas less scheme-

relevant visual elaboration, as manipulated in

the present study, is not retained well. These

results also hi^light the fact that various

measures of recognition memory tap very different aspects of what is retained in pictures.

References

Bevan, W., & Steger, J. A. (1971). Free recall and

abstractness of stimuli. Science, 172, 597-599.

Blaney, R. L., & Winograd, E. (1978). Developmental differences in children's recognition

memory for faces. Developmental Psychohgy,

14, 441-442.

Bousfield, W. A., Esterson, J., & Whitmarsh, G. A.

(1957). The effects of concomitant colored and

uncolored pictorial representations on the

leaming of stimulus words. Jourruil of Applied

Psychohgy, 41, 165-168.

Brown, A. L., & Campione, J. C. (1972). Recognition memory for perceptually similar pictures

in preschool children. Joumai of Experimental

Psychology, 95, 55-62.

Craik, F. I. M., & Rabinowitz, J. C. (1985). Tlie

efFect of presentation rate and encxxling task on

age-related memory de&cits. Journal of Gerontology, 40, 309-315.

Dirks, J., & Neisser, U. (1977). Memory for objects

in real scenes: The development of recognition

and recall. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 23, 315-328.

Evertson, C. M., & Wicker, F. W. (1974). Pictorial

concreteness and mode of elaboration in children's leaming. Journal of Experimental Child

Psychohgy, 17, 264-270.

Friedman, A. (1979). Framing pictures: The role of

knowledge in automatized encoding and memory for gist Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 108, 316-355.

Coodman, C. S. (1980). Picture memoiy; How the

action schema affects retention. Cognitive Psychohgy, 12, 473-495.

Haith, M. M., Morrison, F. J., & Sheingold, K.

(1970). Tachistoscopic recognition of geometric

forms by children and adults. Psychonomic Science, 19, 345-347.

Hofftnan, C. D., & Dick, S. A. (1976). A developmental investigation of recognition memory.

Child Devehpment, 47, 794-799.

Laughery, K. R., Alexander, J. V., & Lane, A. B.

(1971). Recognition of human faces: Effects of

target exposure time, target position, pose position and type of photograph. Journal of Applied Psychohgy, 55, 477-483.

Mackworth, N. H., & Bmner, J. S. (1970). How

adults and children search and recognize pictures. Human Devehpment, 13, 149-177.

Mandler, J. M., & Ritchey, C. H. (1977). Long-tenn

memory for pictures. Journal of Experimental

Psychohgy: Human Leaming and Memory. 3,

386-396.

Kathy Pezdek

Mandler, J. M., Seegmiller, D., & Day, J. (1977). On

the ccxling of spatial information. Memory and

Cognition, 5,10-16.

Naus, M. U Omstein, P. A., & Aivano, S. (1977).

Developmental changes in memory: The ef'

fecte of prcK:es8lng time and rehearsal instruc'

tions. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 2a, 23^7-251.

Nelson, T. O., Metzler, J., & Reed, D. A. (1974).

Role of details in tiie long-tenn rec:ogmticm of

pictures and verbal descripticms.J'cmma/ of Experimental Psychohgy, 102,184-186.

Nickerson, R. S. (1965). Short-term memoiy for

complex visual configurations: A {demonstration of capacity. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 19,155-160.

Nickerson, R. S.,ficAdams, M. J. (1979). Long-tenn

memory for a conunon object Cognitive Psychohgy, 11,287-307.

Park, D. C., Puglisi, J. T , & Sovaoool, M. (1984).

Picture memory in older adults: Effects of cx>ntextual detail at encoding and retrieval. Journal

cf Gerontohgy, 39,213-215.

Pezdek, K., & Chen, H.-C. (1982). Developmental

di£ferences in the role of detail in picture

recognition memory. Journal of Experimental

Child Psychohgy, 33» 207-215.

Pezdek, K., 6c Miceli, L. (1982). Ufe-span diSerences in memoiy integraticm as a &mction of

prcKiessing time. Devehpmental Psychohgy,

18,485-490.

815

Potter, M. C. (1976). Short-term conceptual memory

for pictures. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Leaming and Memory, 2, 509522.

Potter, M. C , & Levy, E. L (1969). Recognition

memory for a rs^id sequence of pic:tures> Journal of Experimental Psychohgy, 81,10-15.

Reese, H. W. (1970). Inuigery and contextual meaning. In H. W. Reese (Chair), Imagery in children's leaming: A symposium. Psychohgical

.Bulletin, 73,40^-414.

Shepaid, R. N. (1967). Recognition memory for

words, sentences, and pictures. Joumo/ of Verbal Leaming and Verhal Behavior, 6,156-163.

Standing, L., Conezio, J., & Haber, R. N. (1970).

Perception and memory for pictures: Singletrial leaming of 2500 visual stimuli. Psychonomic Science, 19, 73-74.

Tversky, B., & Shennan, T. (1975). Picture memoiy

improves with longer on time and oS time.

Journal of Experimental Psychohgy: Human

Leaming and Memory, 104,114-118.

Vurpillot, E. (1968). The development of scanning

strategies and their relation to visual differentiation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychohgy, 6,632-650.

Wii^field, A., Poon, L. W., Lombardi, L., &

Lowe, D. (1985). Speed of processing in normal

^ n g : Effects of speech rate, linguistic stnio

ture, and processing tixae. Journal of Gerontology, 40,579-585.