The Bodleian Library and its Incunabula Alan Coates

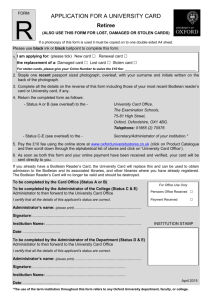

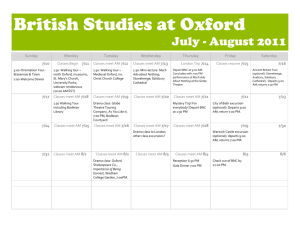

advertisement