Document 14571558

advertisement

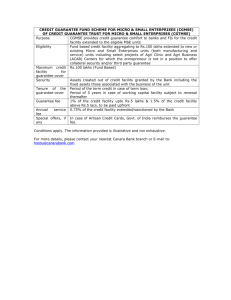

Evaluation on the Effectiveness of the Credit Guarantee Scheme in * Thailand *This dissertation is in the proposal stage Nawapol Pinyoanantapong Ph. D., Economics ABSTRACT Market failures, i.e. imperfect information and positive externalities, rationalize the government intervention in financial markets for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Among many tools of intervention, credit guarantee is viewed to be relatively market-friendly as it can solve the right financial access barrier of the SMEs, i.e. lack of collateral, without substituting the markets like other vehicles do. However, the challenge for guarantee schemes is that there is always a trade-off between financial sustainability, and financial and economic additionalities. Certain level of loss, covered by government subsidies, may be acceptable if the scheme can generate additionalilies satisfactorily. My dissertation, therefore, aims to evaluate the economic addtionalities, in terms of improvement in sales, profit, and tax payment, of the incorporated firms in Thailand after using the credit guarantee by adopting the matching method to deal with the selection bias. Whether or not the guarantee scheme can lead to the financial and economic additionalities is still controversial. Some empirical studies find the positive addtitionalities of the schemes in Japan, US, Canada, Colombia, and Korea (See 4-11), while other literature points out the ineffectiveness of the scheme in Japan (See 4 and 5). Panyanukul, Promboon, and Vorranikulkij (2014), the first and only one empirical study on the Thailand case, find the positive effect of the guarantee in terms of financial additionalities (See 12). However, There exists some limitation regarding the data set, which is biased toward large SMEs and insufficient analysis on the economic additionalies. Recognizing the important role of the SMEs, difficulties in financial access, and market failures, policy makers have been introducing lots of measures to foster the SME activities. Among many tools of the intervention, credit guarantee is viewed to be relatively market-friendly, as it can solve the right financial access barrier of the SMEs, i.e. lack of collateral, without substituting the market like other vehicles do. However, the challenge for guarantee schemes is that there is always a trade-off between financial sustainability, and financial and economic additionalities. Financial additionalities are defined as improvement in the conditions of the guaranteed loans such as lower collateral requirement, lower interest rates, or longer repayment term, while economic additionalities are defined as improvement in the performance of SMEs after receiving the guarantee, for instance number of employment, profit, or export volume (See 1, 2, 3). Certain level of loss, covered by the government subsidies, may be acceptable if the schemes can generate financial and economic additionalities satisfactorily (given that the scheme condition is already designed appropriately). CONCLUSIONS AND EXPECTED RESULTS To deal with this selection bias, Heckman-model control function, instrumental variables, and matching method have been developed (See 4, 10, 12, 13, and 14). Panyanukul, et al. (2014) introduce the Heckman-model to evaluate the Thai guarantee scheme (See 12). However, an efficient Heckman-model requires exclusion restriction, which they have not taken into account. To avoid the exclusion restriction in the Heckman model, matching method can be substituted (See 13 and 14). Certain level of the scheme loss may be acceptable if the scheme can generate additionalilies satisfactorily (given that the scheme is already designed properly). This dissertation, therefore, aims to evaluate the economic addtitionalities of the incorporated firms that use the guarantee in Thailand by adopting the matching method to deal with the selection bias problem. This dissertation, as the second attempt on the Thailand case, therefore, aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the guarantee scheme in Thailand in terms of economic addtionalities by using the dataset from the Business Data Warehouse, which consisted of all active incorporated firms in Thailand. With the matching-method estimation, we can overcome the selection bias by creating the “counterfactual” group of nonguarantee users who have “statistically” identical characteristics as the guaranteed firms based on the propensity score of the guarantee participation estimated from the probit model. The dependent variable is a binary variable representing whether or not the firms participate the program. The independent variables are a set of factors Xt-1 that determine the program participation such as timeinvariant characteristics In (age, size, sector, and location), and time-variant financial performances Pn (fixed asset ratio, current asset ratio, return on asset ratio, and debt to equity ratio). WHY WE NEED BIG DATA? Pr(Guaranteet = 1| Xt-1) = Φ (γnIn,i + λnPn,i,t-1) Most importantly, besides the controversy of the findings in the previous studies, to evaluate the contribution of the guarantee scheme is not simple as it sounds like. Conventionally, most research has been using the aggregate data or the firm-level dataset that is consisted solely of the guaranteed firms. Then, we match the guaranteed firms with the nearest neighboring non-guaranteed firms in each calendar year using the propensity score as a distance measurement. Next, we construct the outcome equation as follows: INTRODUCTION SMEs play an important role in the economy as they provide the majority of job opportunities and are the key players for economic recovery during the recession. However, the SME sector is highly volatile as despite emerging of numerous new small businesses, enormous SMEs also collapse in the same time. Moreover, the SMEs generate lower productivity growth than the large firms. Due to their lack of collateral, financial access is one of the obstacles for the SMEs to improve their productivity and/or to retain their business. In addition, There exist the market failures, i.e. imperfect information and positive externalities, in the SMEfinancing market. MODEL SPECIFICATION Yi,t = ai + δ1Pi,t + δ2Pi,t-1 + ut + vi,t , Using the aggregate data, even though the scheme demonstrates the positive effect on the economy, we cannot conclude that it has effectively been used. It could possibly be the case that commercial banks force their former clients (which can get the loans even without the guarantee) to use the guarantee so that the banks are less exposed to the risks. Then, the contribution to the economy would come from the larger profit of the commercial banks that force the SMEs to use the guarantee, implying that the benefit of the guarantee falls upon financial sector instead of SME sector, which is supposed to be the real target of the scheme. Therefore, to justify the effectiveness of the guarantee scheme, we need to use the firm-level data to show that the guaranteed firms access to better loan conditions or/and have better performance than the non-guaranteed ones do. This also implies that we need to have the dataset that consists of both guaranteed and nonguaranteed firms. Furthermore, we cannot just easily compare those two cases using the actual data since there could be some characteristics that determine the scheme participation and outcome simultaneously, i.e. selection bias. Our evaluation could be misestimated if we do not take care of this selection bias. Yi,t represents firm outcomes (sales, profit, tax payment); ai is a firm-level fixed effect to control unobserved characteristics; Pi,t and Pi,t-1 are binary variables expressing whether or not firms participate the guarantee program; ut is a year-fixed effect; and vi,t represents a random shock. DATA Our sample is constructed from the Business Data Warehouse (BDW) provided by Ministry of Commerce, Thailand, which is consisted of approximately 600,000 active incorporated firms in Thailand. The firm’s basic information, i.e. location, firm size, age, and sector, as well as financial statement, i.e. the balance sheet and income statement, are available. Since the current guarantee scheme was first launched in 2009, the firm information from 2008 to 2013 will be used for our analysis. www.PosterPresentations.com REFERENCES 1. Green, A. (2003). Credit guarantee schemes for small enterprises: An effective instrument to promote private sector-led growth?. The United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) Working Paper, No. 10, August 2003. 2. Levitsky, J. (1997). Credit guarantee schemes for SMEs: An international review. Small Enterprise Development, 8(2), 4-17 3. OECD. (2010). Facilitating access to finance: Discussion paper on credit guarantee schemes. France: OECD 4. Uesugi, I., Sakai, K., & Guy, M. Y. (2006) Effectiveness of credit guarantees in the Japanese loan market. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 24(4), 457–480 5. Wilcox, J., A. & Yasuda, Y. (2008) Do government loan guarantees lower or raise banks’ non- guaranteed lending? Evidence from Japanese banks. Paper presented at the World Bank Conference on Partial Credit Guarantees, March 13-14, 2008. 6. Craig, B., R., Jackson, W., E., & Thomson, J., B. (2005) SBA-loan guarantees and local economic growth. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Working Paper 05-03. 7. Hancock, D., Peek, J., & Wilcox, J., A. (2007). The repercussions on small banks and small business of bank capital and loan guarantees. AFA 2008 New Orleans Meeting Paper 8. Industry Canada. (2010). Study of the economic costs and benefits of the canada small business financing program. 9. Riding, A., L., Madill, J., & Haines, G., Jr. (2006) Incrementality of SME loan guarantees. Small Business Economics, 29(1-2) 47-61. 10. Arraiz, I., Melendez, M., & Stucchi, R. (2014). Partial credit guarantees and firm performance: evidence from Colombia. Small Business Economics, 43, 711-724 11. Kang, J., W., & Heshmati, A. (2007) Effect of credit guarantee policy on survival and performance of SMEs in Republic of Korea. Small Business Economics, Online publication. 12. Panyanukul, S., Promboon, W., & Vorranikulkuj, W. (2014). Role of government in improving SME access to financing: credit guarantee schemes and the way forward. Bank of Thailand Symposium 2014. 13. Wooldridge, J. ,M. (2001). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. 14. Heckman, J., & Navarro-Lozano, S. (2004). Using matching, instrumental variables, and control functions to estimate economic choice models. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(1), 30-57. CONTACTS FIRM SIZE (THAI BAHT) RESEARCH POSTER PRESENTATION DESIGN © 2012 The followings are some of the expected results. Firstly, in terms of firm characteristics, we expect to see the guaranteed firms with riskier characteristics (e.g. younger, lower income, lower collateral etc.) than the firms that can access to the loans without the guarantee. Secondly, since the service sector tends to be relatively labor-intensive and, thus, have more constraint to the financial access, we anticipate to see more contribution of the guarantee to the economy particularly in this sector. Lastly, unfortunately, due to the limitation of the loan data availability, we cannot evaluate the financial additionalities. However, even though we fail to do so, considering that the financial system in Thailand is relatively competitive, we can expect to see financial addtionalities to some extent, otherwise banks may lose their customers to other banks that can provide more attractive loan conditions with the guarantee. Additionally, even though the incentive misalignment (the increase in non-performing guarantee) are not directly taken into account, as long as the firms can make higher income, it implies that the incentive misalignment is less likely to occur. SECTOR E-mail: ouunawapol@msn.com, or nawapol.pinyoanantapong@cgu.edu