Document 14569546

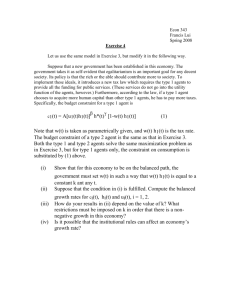

advertisement