Global Employment Trends January 2009

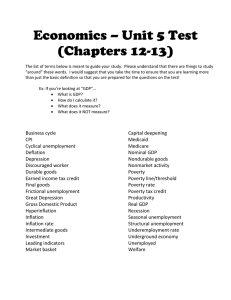

advertisement