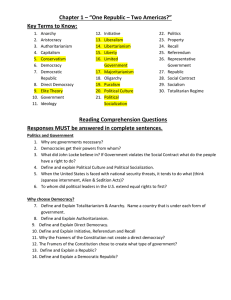

M , T

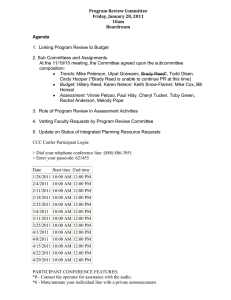

advertisement