Common Ground for Building Our City:

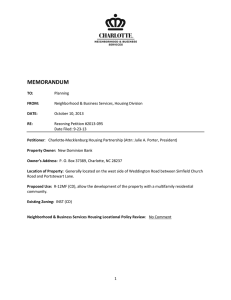

advertisement