Headship and Homeownership What Does the Future Hold? Laurie Goodman

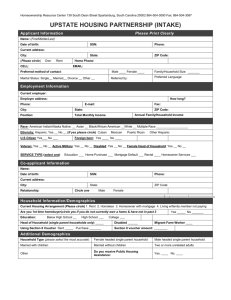

advertisement