Volume XXX Number 1 2012

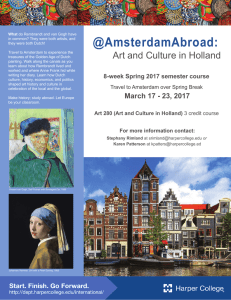

advertisement