Volume XXVIII Number 1 2010

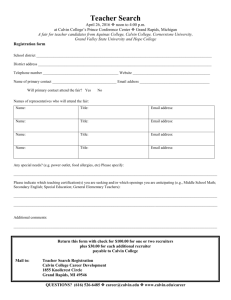

advertisement