Volume XXVII Number 1 2009

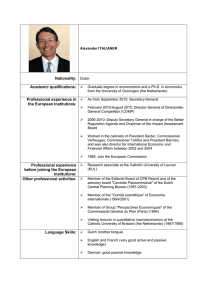

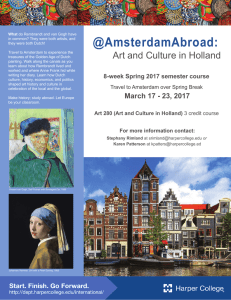

advertisement