Document 14552057

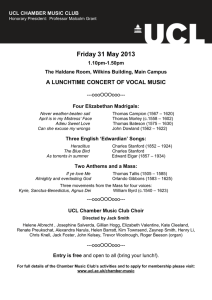

advertisement