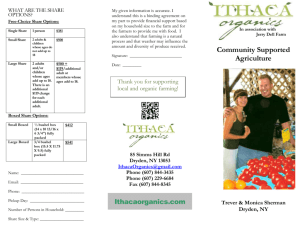

“What’d Life Be Without Home Grown Tomatoes?”

advertisement