Document 14546347

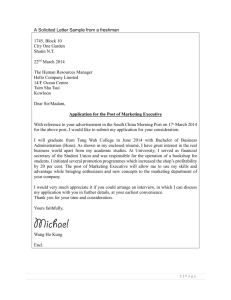

advertisement