Specialized Felony Domestic Violence Courts: Lessons on Implementation and Impacts from the Kings

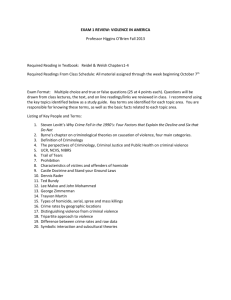

advertisement