Document 14544992

advertisement

The SIJ Transactions on Industrial, Financial & Business Management (IFBM), Vol. 3, No. 1, January 2015

The Importance of Supervisor Support

during Organizational Change

Paul Chou*

*Assistant Professor, Department of Business Administration, Minghsin University of Science & Technology, TAIWAN, ROC.

E-Mail: pchou{at}must{dot}edu{dot}tw

Abstract—Given that countless companies fail to implement changes successfully, the aim of this study is to

explore a deeper understanding of the complexities of employees’ attitudinal and behavioral reactions to

organizational changes in hopes of improving the chances of the success of organizational changes. The results

from the data collected from 319 employees within 20 farmers’ associations in Taiwan confirm that perceived

supervisor support matters for successful organizational change. The proof of the importance of supervisor

support during organizational change not only provides an additional understanding of the mechanism through

which perceived supervisor support influences follower’s behavioral support for change, but also allows

management and HRM practitioners to focus on certain perspectives, with the ultimate intention of enhancing

the possibility of successful organizational change. Practical implications and contributions of this study are

discussed as are limitations of the studies and suggestions for future research.

Keywords—Affective Commitment to Organization; Behavioral Support for Change; Human Resource

Management; Organizational Change; Perceived Supervisor Support; Self-Efficacy.

Abbreviations—Affective Commitment to Organization (ACO); Average Variance Extracted (AVE);

Behavioral Support for Change (BSC); Composite Reliability (CR); Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA);

Farmer Association (FA); Human Resource Management (HRM); Perceived Supervisor Support (PSS); SelfEfficacy (SLF); Structural Equation Modeling (SEM).

I.

G

INTRODUCTION

IVEN that organizational changes of increasing

frequency and severity become the norm and

countless companies fail to implement organizational

changes successfully [Beer & Nohria, 8], an improvement in

the understanding of employees’ behavioral support for

change is increasingly important [Fedor et al., 22; Jaros, 34]

for the sake of implementing organizational change

successfully. In other words, it is important for researchers to

provide insights that can improve the chances of the success

of these changes [Jaros, 34; Parish et al., 51]. This is

particularly true for the case of Farmers’ Associations in

Taiwan. Pressure from increasing competition in both

external and internal markets drove Farmers’ Associations to

initiate organizational change in order to improve the

efficiency and quality of their service and to reduce

operational costs. This provides a excellent opportunity to

study the importance of supervisor support during

organizational change.

In essence, organizational change is essentially stressful,

since the process of organizational change creates fear,

uncertainty and doubt [Jaskyte, 35; Vakola & Nikolaou, 58]

and it causes changes in and demands the readjustment of an

average employee’s normal routine [Leana & Barry, 42]. In

ISSN: 2321-242X

that event, the successful implementation of organizational

change often requires employee acceptance and behavioral

support [Fedor et al., 22; Miller et al., 50]. In line with this,

Positive attitudes to change and behavioral support for

change were found to be vital in achieving organizational

goals and in succeeding in change programme [Eby et al., 17;

Meyer & Herscovitch, 48; Miller et al., 50; Parish et al., 51].

With respect to individual’s attitudes toward change,

employees tend to interpret change as a perceived loss of

control [Lamm & Gordon, 40]. From this perspective,

perceived control is influential in helping individuals to

accept change [Wanberg & Banas, 60]. It is suggested that

people who are confident in their abilities can mitigate the

stressful effects of a threatening event (e.g., organizational

change) [Schaubroeck & Merritt, 55]. In view of this, selfefficacy is likely to enhance individuals’ perceived control by

helping individuals to view organizational change as an

opportunity, rather than as a threat [Jimmieson et al., 36;

Krueger & Dickson, 39].

Further, organizational commitment is suggested as one

of the most important determinants of successful

organizational change [Iverson, 33]. Specifically speaking,

the higher employees’ commitment to their organization the

greater their willingness to accept organizational change

[Cordery et al., 12; Guest, 27]. Empirically, supportive

© 2015 | Published by The Standard International Journals (The SIJ)

1

The SIJ Transactions on Industrial, Financial & Business Management (IFBM), Vol. 3, No. 1, January 2015

leadership has been found to be conceptually and empirically

linked to followers’ commitment and supportive behavior for

change [Herold et al., 29; 30; Herscovitch & Meyer, 31] and

their efforts in implementing change [Higgs & Rowland, 32].

Despite the importance of employees’ acceptance and

supportive behavior toward organizational change, related

studies of employees’ supportive behavior for change are few

[Lamm & Gordon, 40; Meyer et al., 49; Schyns, 57].

Furthermore, given that most studies of change focus on the

organization-level phenomena, as opposed to the individuallevel [Wanberg & Banas, 60] and empirical research into the

roles and behaviors of leaders in a change context, per se, is

relatively scarce [Fedor et al., 22], there is a strong need for a

systematic empirical study of why and how Taiwanese

employees react behaviorally to support organizational

change [Fedor et al., 22; Herold et al., 29; 30; Jaros, 34] in

response to supervisory support. Thus, this study aims to

answer two questions: Dose supervisor support matter for

successful organizational change and how if it does?

II.

LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Perceived Supervisor Support and Behavioral Support

for Change

In the workplace, supervisors play an important role in

structuring the work environment by providing information

and feedback to employees [Griffin et al., 26] and by

controlling the powerful rewards that acknowledge the

employee’s personal worth [Doby & Caplan, 15]. As such,

the social interaction between an employee and his/her

immediate supervisor is the primary determinant of an

employee’s attitude and behavior in the workplace [Wayne et

al., 61].

Conceptually, employees develop general views

concerning the degree to which supervisors value their

contributions and care about their well-being [Eisenberger et

al., 20]. According to the concept of personification of

organization [Levinson, 43], the immediate supervisor’s

behaviors are likely to be perceived by employees as

representative of organizational decisions [Griffin et al., 26]

and that supportive treatment by the employees’ immediate

supervisors is interpreted as the organization’s benevolence.

Consequently, individuals show increased perceived

organizational support when they receive supervisory support

[Malatesta, 46]. As such, on the basis of the norm of

reciprocity, employees who perceive organizational support

develop a “felt obligation” to care about the organization’s

welfare and to help the organization achieve its objectives

(e.g., the success of organizational change) [Eisenberger, et

al., 18; 19; Lind et al., 44].

Supervisory support is also displayed in terms of trust

and a deep concern for the subordinates’ needs [Iverson, 33].

From this perspective, employees who trust and appreciate

their supervisors are prone to have a positive perception

toward organizational change and tend to demonstrate

behavioral support for organizational change. In that case,

employees who perceive supervisory support not only tend to

ISSN: 2321-242X

interpret the organization’s gains and losses as their own, but

also tend to perceive the outcomes of organizational change

positively [Fedor et al., 22], which can, in turn, increase their

behavioral support for change. Therefore, this study’s first

hypothesis predicts a direct positive relationship between

perceived supervisory support and behavioral support for

change:

H1: There is a direct positive relationship between

perceived supervisor support and behavioral support for

change.

2.2. The Mediating Role of Affective Commitment to

Organization

According to Baron & Kenny [7], the role of affective

commitment to organization as a mediator of the perceived

supervisor support–behavioral support for change

relationship is supported, in part, by the links between; (1)

perceived supervisor support and affective commitment to

organization, (2) perceived supervisor support and behavioral

support for change and (3) affective commitment to

organization and affective commitment to organization.

2.2.1. Perceived Supervisory Support

Commitment to Organization

and

Affective

Most measures of organizational commitment assess affective

commitment affective commitment to organization

[Colquittet al., 10], which is defined as the degree to which

employees identify with the company and make the

company’s goals their own [Allen & Meyer, 1990]. As

previously noted, supportive behavior demonstrated by the

employees’ immediate supervisors is interpreted by recipients

as the organization’s benevolence. According to the norm of

reciprocity [Gouldner, 25], employees who perceive the

organization’s benevolence are more prone to identify with

the company and tend to adopt the company’s goals as their

own.

Empirically, previous research suggests that leadership is

a key determinant of effective commitment to the

organization [Avolio et al., 4]. Specifically, many empirical

results indicate that supportive leadership is positively

associated with affective commitment to organization [Avolio

et al., 4; Dumdum et al., 16; Glisson & Durick, 24; Jaskyte,

35; Judge & Bono, 37; Mathieu & Zajac, 47; Podsakoff et al.,

52]. Therefore, it is plausible to assume that perceived

supervisory support influences the followers’ affective

commitment to an organization.

2.2.2. Affective Commitment to Organization and Behavioral

Support for Change

According to Herscovitch & Meyer [31], there are three kinds

of behavioral support for change: compliance, cooperation

and championing. Compliance refers to employees’

willingness to do what is required of them by the

organization, in order to implement change. Cooperation

refers to employees’ acceptance of the “spirit” of the change

and their willingness to do little extra tasks to make it work.

Finally, championing refers to employees’ willingness to

embrace the change and to “sell” it to others.

© 2015 | Published by The Standard International Journals (The SIJ)

2

The SIJ Transactions on Industrial, Financial & Business Management (IFBM), Vol. 3, No. 1, January 2015

Previous studies indicated that affective organizational

commitment plays an important role in employee’s

acceptance of change [Darwish, 14; Iverson, 33; Lau &

Woodman, 41; Vakola & Nikolaou, 58]. In essence,

employees with a strong affective commitment to an

organization are likely to value the course of action that is

necessary for successful change and are therefore willing to

do whatever is required to achieve the target of that action

[Meyer et al., 49]. In other words, those who strongly identify

with the company and who perceive the company’s goals as

their own (i.e., strong affective commitment to an

organization) are willing to do more than is required of them

during organizational change [Vakola & Nikolaou, 58], even

if it involves some personal sacrifice [Meyer & Herscovitch,

48; Meyer et al., 49]. Therefore, it is plausible to assume that

there is a positive relationship between affective commitment

to an organization and behavioral support for change.

Accordingly, on the basis of all of the inferences

discussed above for the simple bivariate associations

incorporated in the initial hypotheses, hypothesis 2 is stated

as:

H2: Affective commitment to an organization mediates

the relationship between perceived supervisor support and

behavioral support for change.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Self-efficacy

The role of self-efficacy as a mediator of the perceived

supervisor support and behavioral support for change

relationship is supported, in part, by the links between; (1)

perceived supervisor support and self-efficacy, (2) perceived

supervisor support and behavioral support for change and (3)

self-efficacy and behavioral support for change [Baron &

Kenny, 7].

2.3.1. Perceived Supervisor Support and Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is defined as an employee’s belief in his/her

capability to mobilize motivation, cognitive resources and the

courses of action needed to exercise control over events in

their lives [Wood & Bandura, 62]. According to this

definition, self-efficacy defines the extent to which an

individual believes him/herself to be capable of successfully

performing a specific behavior or a specific task [Bandura, 6]

and enables him/her to integrate cognitive, social, emotional

and behavioral sub-skills, in order to accomplish a particular

objective [Judge et al., 38]. Empirically, self-efficacy has

consistently been found to influence thought patterns,

behaviors and emotional arousal [Armenakis et al., 3].

With respect to the relationship between supervisory

support and self-efficacy, Bandura [6] suggests four sources

of self-efficacy: Mastery experience, vicarious experience,

verbal persuasion and emotional arousal. In practice, a

supportive supervisor can provide the opportunity for

mastery/vicarious experience to their subordinates, in

addition to serving as a model to encourage their

subordinates, through verbal persuasion [Schyns, 57]. On the

other hand, supervisory support, can also be viewed as a

means of control over some aspect of the working

environment [Daniels & Guppy, 13].

In sum, supervisory support in the workplace is

perceived by its recipients as a major organizational resource

upon which they can rely while performing their daily jobs.

Therefore, the perceived availability of instrumental support

from a supervisor can enhance their confidence that the job

will be done well [van Yperen & Hagedoorn, 59].

Accordingly, it is plausible to reason that supervisory support

allows a subordinate to feel confident in the ability to

confront challenges and overcome problems successfully in

the workplace, which in turn enhances his/her self-efficacy.

2.3.2. Self-efficacy and Behavioral Support for Change

For decades, self-efficacy has been consistently found to

influence thought patterns, behaviors and emotional arousal

[Armenakis et al., 3]. In essence, the greater a person’s selfefficacy, the more confident is he or she of being successful

in a particular task domain [Prussia et al., 54]. In other words,

self-efficacy has a critical effect on an individual’s perceived

ability and willingness to exercise control in the workplace

[Litt, 45]. Specifically, employees with high self-efficacy are

more prone to strive to complete a difficult task that results

from organizational change and less prone to give up when

obstacles appear during organizational change [Schyns, 57].

It has also been suggested that a strong sense of self-efficacy

helps to equip the members of an organization with the ability

to cope with organizational change [Armenakis et al., 3].

As previously noted, organizational change is stressful.

In that case, people who are confident in their abilities (high

self-efficacy) can mitigate the stressful effects of demanding

jobs during organizational change [Schaubroeck & Merritt,

55]. Consequently, employees with high self-efficacy will

persist longer when faced with obstacles in their new tasks

and will expend more effort [Schyns, 57]. In short, those with

greater self-efficacy are thought to be more active and

persistent in their efforts (e.g., supportive behavior to change)

by demonstrating supportive behavior during organizational

change. Therefore, it is suggested that there is a positive

association between self-efficacy and behavioral support for

change.

Accordingly, based on the inferences discussed above for

the simple bivariate associations incorporated in the initial

hypotheses, hypothesis 3 is stated as:

H3: Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between

perceived supervisor support and behavioral support for

change.

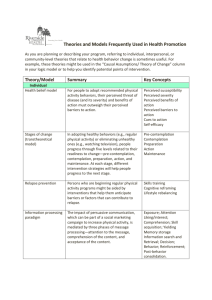

Figure 1: The Research Framework

ISSN: 2321-242X

© 2015 | Published by The Standard International Journals (The SIJ)

3

The SIJ Transactions on Industrial, Financial & Business Management (IFBM), Vol. 3, No. 1, January 2015

III.

SAMPLE & MEASURES

3.2.3. Affective Commitment to Organization (ACO)

3.1. Participants

Survey data for this study was collected from employees of 3

Taiwanese farmer’s associations (FA). A total of 500

questionnaires were sent to the 2 FAs’ general managers, who

agreed to participate this survey and hand-delivered by the

heads of the human resources department, to demonstrate

top-level support of the study. Attached to each questionnaire

was a cover letter, explaining the purpose of the survey, and a

return envelope, which ensured the confidentiality of

respondents by allowing them to send back their replies

independent of their organizations. A total of 413

questionnaires were returned (83% response rate), with 388

valid questionnaires, after screening (78%). Descriptive

statistics for the valid respondents are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Descriptive Profile of Respondents

Male

Gender

Female

Managerial position

Job Rank

Non-managerial position

Under 30

31-40

Age

(years)

41-50

Over 50

Over 15 years

11-15 years

Seniority

(years)

5-10 years

Under 5 years

Masters

Degree

Education

Diploma

High school

Over 800,000

600,001 – 800,000

Annual income (NT$)

400,001 – 600,000

Less 400,000

34%

66%

10%

90%

13%

28%

28%

31%

51%

14%

14%

21%

3%

21%

32%

44%

25%

31%

24%

20%

3.2. Measures

Unless otherwise stated, all responses were made on using a

6-point scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (6)

strongly agree.

3.2.1. Perceived Supervisor Support (PSS)

Perceived supervisor support was assessed using 7 items

developed by Cummings & Oldham (1997) (e.g., “My

supervisor really cares about my well-being.”). The internal

consistency of this 4-item scale was 0.96 for this sample.

3.2.2. Self-efficacy (SLF)

Self-efficacy was measured using the ten items developed by

Schwarzer et al., [56] (e.g., “I can always manage to solve

difficult problems if I try hard enough.”). The internal

consistency of this ten-item scale was 0.89 for this sample.

ISSN: 2321-242X

Affective commitment to the organization was measured

using the six items developed by Meyer, Allen & Smith

(1993) (e.g., “I really feel that this organization’s problems

are my own.”). The internal consistency of this six-item scale

was 0.83 for this sample.

3.2.4. Behavioral Support for Change (BSC)

Supportive behavior to change was measured using the 17

items developed by Herscovitch & Meyer [31] (e.g. “I adjust

the way I do my job as required by this change.”

[compliance]; “I work toward the change consistently.”

[cooperation] and “I encourage the participation of others in

the change.” [championing]). The internal consistency of this

six-item scale was 0.94 for this sample.

IV.

RESULTS

4.1. Analysis

Before testing the study hypotheses, confirmatory factor

analysis (CFA) was conducted with AMOS software

[Arbuckle, 2] to examine the convergent and discriminant

validity of the study measures. Given the large number of

items (40) relative to the sample size (319), the procedures

recommended by Mathieu & Farr [47] were followed by

creating four, five and three composite indicators for

perceived supervisor support, self-efficacy and affective

commitment to organization, respectively. For the indicators

of behavioral support for change, three sub-dimensions (i.e.,

compliance; championship and cooperation; intellectual

stimulation) were used in order to maintain an adequate

sample-size-to-parameter ratio.

Following the approach suggested by Andersen &

Gerbing [1], convergent validity is demonstrated when the

path loading (λ) from an item to its latent construct is

significant and exceeds 0.50. All path loading (λ) in this

study, as shown in Table 2, was above 0.50 (0.72-0.95). In

addition, convergent validity is also adequate when the

constructs have an average variance extracted (AVE) of at

least 0.50 and composite reliability (CR) is greater than 0.6

[Hair et al., 28]. As shown in Table 2, the AVEs of all four

constructs in this study exceeded 0.50 (0.89-0.95) and CRs of

all four constructs exceeded 0.6 (0.63-.80). Thus, all

constructs in our study demonstrate adequate convergent

validity.

To assess discriminant validity, the procedures outlined

by Fornell & Larcker [23] were employed to examine

whether the square root of AVE for the two constructs should

exceed the correlation between the constructs. As shown in

Table 2, the square root of AVE for the two constructs

exceeded the correlation between the constructs. Thus, all

tests of reliability and validity lead to the conclusion that the

measures used in later statistical analyses fall within

acceptable reliability and validity criteria.

© 2015 | Published by The Standard International Journals (The SIJ)

4

The SIJ Transactions on Industrial, Financial & Business Management (IFBM), Vol. 3, No. 1, January 2015

Variable

Mean

SD

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics and Correlations between Study Variables

Item

Cronbach α

CR

1

loading (λ) (min.-Max.)

.96

.957

(.85 - .94)

(.97)

.89

.94

(.72 - .84)

.35***

.83

.94

(.80 - .95)

.24***

.94

.94

(.81 - .89)

.43***

2

3

4

1. PSS

4.31

1.09

2. SLF

4.30

.67

(.94)

3. ACO

4.68

.81

.25***

(.94)

4. BSC

4.70

.65

.52***

.32***

(.94)

Note:

PSS=perceived supervisor support; SLF=self-efficacy; ACO=Affective commitment to organization; BSC=behavioral support for change.

CR = composite reliability.

Item loading (λ) is standardized.

Values along the diagonal represent the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE).

Given that the data were collected from a single source,

in addition to the evidence of acceptable discriminant and

convergent validity [Conway & Lance, 11], the procedures of

Harman’s one-factor test recommended by Podsakoff et al.,

[53] were conducted to test whether the hypothesized fourfactor model was superior to the one-factor model in order to

rule out the influence of common method bias. The result

shows that the four-factor model (GFI= .91; CFI= .95; TLI =

.94; RMSEA = .079) had a better fit than did the single-factor

model (GFI= .46; CFI= .44; TLI = .34; RMSEA = .26). Thus,

although this study acknowledges that common method

variance may be present in the data, it does not appear that

common method bias is a serious problem in this study.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

The mean, the standard deviation and the correlations

between the research variables are shown in Table 2. As

predicted, the pattern of correlations is consistent with the

hypothesized relationships. That is, perceived supervisor

support is positively correlated with self-efficacy (0.35,

p<0.001), affective commitment to organization (0.24,

p<0.001) and behavioral support for change (0.43, p < 0.001);

Self-efficacy is positively correlated with behavioral support

for change (0.52, p<0.001) and affective commitment to

organization is positively correlated with behavioral support

for change (0.32, p<0.001). The results provide preliminary

support for the hypothesized direction.

More conclusive specific tests of these hypotheses were

conducted with Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

analyses, using the AMOS software [Arbuckle, 2] to assess

the structural model specifying the relations between the

latent constructs. Table 3 presents fit indices for the

hypothesized model, along with an alternative model with

which to test whether a fully mediating relationship exists

between perceived supervisor support and behavioral support

for change.

Table 3: Competitive Model Test

perceived supervisor support to behavioral support for

change, does not result in a significant improvement in model

fit, with a RMSEA of 0.084, a CFI of 0.94, a GFI of 0.90, and

an TLI of 0.93. This result indicates that self-efficacy and

affective commitment to organization partially mediate the

relationship between perceived supervisor support and

behavioral support for change.

Standardized parameter estimates for the best-fitting

model (Hypothesized Model) are shown in Figure 2. For ease

of presentation, only the structural model is presented rather

than the full measurement model. Examination of the path

coefficients reveals that perceived supervisor support is

uniquely related to self-efficacy and affective commitment to

organization in the positive direction and has significant

direct associations with behavioral support for change; selfefficacy and affective commitment to organization are

separately related to behavioral support for change in the

positive direction.

Figure 2: The Final Model

In summary, as predicted, there is a direct positive

relationship between perceived supervisor support and

behavioral support for change. However, with respect to the

mediating effects, affective commitment to organization and

self-efficacy, only partially mediate the relationship between

perceived supervisor support and behavioral support for

change.

X² df X²/df △X² RMSEA CFI TLI GFI

Hypothesized model 299.748 85 3.526 23.06 .080

.95 .94 .91

Alternative Model

322.81 86 3.754

.084

.94 .93 .90

* Alternative Models only removed the direct path from PSS to BSC.

5.1. Findings

Results of comparison show that the hypothesized model

adequately explains the data as indicated by a RMSEA of

0.080, a CFI of 0.95, a GFI of 0.91, and TLI of 0.94, whereas

the alternative model, which removes the direct path from

By and large, the findings of this study support the claims of

Dumdum et al., [16] and Jaskyte [35] that leadership is one of

the most important variables affecting work attitudes (selfefficacy and affective commitment to organization, in this

ISSN: 2321-242X

V.

DISCUSSION & CONCLUSION

© 2015 | Published by The Standard International Journals (The SIJ)

5

The SIJ Transactions on Industrial, Financial & Business Management (IFBM), Vol. 3, No. 1, January 2015

case) and behaviors (behavioral support for change, in this

case). Specifically, the results of this study, same as Chou’s

[9] findings, confirm a positive relationship between

perceived supervisor support and behavioral support for

organizational change.

The model presented in this study supports the efficacy

of supervisory support in developing a subordinate’s positive

attitudes and behaviors toward organizational change. This

model also indicates that, based on the norm of reciprocity

[Gouldner, 25], a supportive leader is likely to strengthen the

affective commitment to organization by enhancing

followers’ “feeling of obligation” and, therefore, increases

their behavioral support for change.

In addition, the current results further support previous

findings on the significance of employees’ affective

commitment to organization on successful organizational

change interventions [e.g. Iverson, 33; Lau & Woodman, 41;

Vakola & Nikolaou, 58] in a non-Western culture such as

Taiwan. In sum, the current results demonstrate that

perceived supervisor support matters during organizational

change.

5.2. Practical Implications

The present study has several practical implications for

organizations, managers and HRM practitioners facing

organizational change. First, the findings of this study suggest

that the success of organizational change lies in the

supportive leadership of individual managers. As such, the

proof of these linkages shows that management and HRM

practitioners should focus on developing supportive

leadership talents to achieve an ultimate increase in

behavioral support for change, directly and indirectly, via

self-efficacy and affective commitment to organization.

Second, this study demonstrates that self-efficacy and

affective commitment to organization respectively account

for the variance in behavioral support for change. As such,

organizations that plan for changes or that are in the process

of change must pay particular attention on how to enhance

their employees’ self-efficacy as well as affective

commitment to organization. In practice, this can be done by

training supervisors/managers how to enhance self-efficacy

and affective commitment to organization by developing

employees’ competencies to strengthen their self-efficacy.

Third, during organizational change, it is critically

important for organizations to identify employees with high

self-efficacy as they are more prone to accept change and are

better to adapt to change [Schyns, 57]. In this regard,

employees with high self-efficacy can serve as change agents

for their colleagues in order to increase the chances of the

successful implementation of organizational change.

5.3. Limitations of this Study

Similarly to other studies, this research also has limitations.

Firstly, the sample is confined to a limited number of

Taiwanese FAs, which limits the generality of its findings

and conclusions either to other FAs or to private enterprises.

Secondly, despite the appropriateness of the use of the

ISSN: 2321-242X

subordinate’s evaluation of supportive leadership, an

affective commitment to an organization and supportive

behavior measures, this approach has potential problems with

common-method bias, as the measures of the research

variables were gathered from the same source, even though a

Harmon single factor test [Podsakoff et al., 53] shows that

common method bias is not a serious problem. Thirdly,

caution must be exercised when interpreting the findings of

this study, because of the possible constraint of non-response

bias. Non-respondents could hold different views with respect

to the variables in question, which could result in survey

estimates that are biased. Finally, this study suffers from the

common limitations of cross-sectional field research,

including an inability to make causal inferences.

5.4. Contributions of this Study

While continuous change is a fact of organizational life for

the organization’s members and organizational changes

become the norm, a better understanding of employees’

reactions to these changes is increasingly important [Fedor et

al., 22]. In this regard, this study has a number of strengths.

Firstly, as already noted, the role and behaviors of leaders in

a change context, per se, is an area that lacks empirical

research [Herold et al., 30]. In other words, little is known

about the differential effects of various aspects of

organizational change on different aspects of the attitudes of

those individuals affected by leadership [Fedor et al., 22].

This study addresses this shortcoming by conducting an

empirical study and, more importantly, the model presented

in this study can serve as a guide for organizations in the

process of change.

Secondly, since the personal bonds that supervisors have

with their employees in the Chinese culture not only

determine their legitimate power and influence [Farh et al.,

21, but also impact their followers’ organizational life [e.g.,

Aycan, 5], investigations of this kind of relationship in the

Chinese context provide a better understanding of the effects

of supervisor support on employees’ attitudes and behaviors

toward change to garner the effectiveness of organizational

change efforts for organizations in the Chinese context.

Thirdly, given the vast majority of studies related to

organizational change and leadership have been conducted in

North America and other Western countries, the results of

this study demonstrate that the effects of supervisor support

on employees’ attitudes and behavior can also be extended

and extrapolated to Asian populations.

To summarize, this study, as predicted, shows the

important role of supportive leadership during organizational

change. The proof of these linkages not only provides an

additional understanding of the mechanism through which

perceived supervisor support influences follower’s behavioral

support for change, but also allows management and HRM

practitioners to focus on certain perspectives, with the

ultimate intention of enhancing the possibility of successful

organizational change.

© 2015 | Published by The Standard International Journals (The SIJ)

6

The SIJ Transactions on Industrial, Financial & Business Management (IFBM), Vol. 3, No. 1, January 2015

REFERENCES

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

J.C. Anderson & D.W. Gerbing (1988), “Structural Equation

Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step

Approach”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 103, No. 3, Pp. 411–

423.

J.L. Arbukle (2003), “AMOS 5.0 [Computer Software]”, SPSS,

Chicago, IL.

A.A. Armenakis, S.G. Harris & K.W. Mossholder (1993),

“Creating Readiness for Organizational Change”, Human

Relations, Vol. 46, No. 6, Pp. 681–703.

B.J. Avolio, W. Zhu, W. Koh & P. Bhatia (2004),

“Transformational

Leadership

and

Organizational

Commitment: Mediating Role of Psychological Empower and

Moderating Role of Structural Distance”, Journal of

Organizational Behavior, Vol. 25, Pp. 951–968.

Z. Aycan (2008), “Cross-cultural Approaches to Leadership”,

Editors: P.B. Smith, M.F. Peterson & D.C. Thomas, “The

Handbook of Cross Cultural Management Research”, Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc, Pp. 219–238.

A. Bandura (1986), “Social Foundations of Thought and

Action”, Prestice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

R.M. Baron & D.A. Kenny (1986), “The Moderator-Mediator

Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research:

Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations”, Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 51, No. 6, Pp.

1173–1182.

M. Beer & N. Nohria (2000), “Cracking the Code of Change”,

Harvard Business Review, Pp. 133–141.

P. Chou (2014), “Dose Supervisor Support Matter for

Successful Organizational Change?” International Academic

Conference on Social Sciences (IACSS), Osaka, Japan.

J.A. Colquitt, D.E. Conlon, M.J. Wesson, O.L. Porter & K.Y.

Ng (2001), “Justice at the Millennium: A Meta-Analytic

Review of 25 Years of Organizational Justice Research”,

Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 86, No. 3, Pp. 425–445.

J. M. Conway & C.E. Lance (2010), “What Reviewers Should

Expect from Authors Regarding Common Method Bias in

Organizational Research”, Journal of Business Psychology,

Vol. 25, Pp. 325–334.

J. Cordery, P. Sevatos, W. Mueller & S. Parker (1993),

“Correlates of Employee Attitude toward Functional

Flexibiltiy”, Human Relations, Vol. 46, No. 6, Pp. 705–723.

K. Daniels & A. Guppy (1994), “Occupational Stress, Social

Support, Job Control, and Psychological Well-being”, Human

Relations, Vol. 47, No. 12, Pp. 1523–1544.

Y. Darwish (2000), “Organizational Commitment and Job

Satisfaction as Predictors of Attitudes toward Organizational

Change in a Non-Western Setting”, Personnel Review, Vol. 29,

No. 5–6, Pp. 6–25.

V.J. Doby & R.D. Caplan (1995), “Organizational Stress as

Threat to Reputation: Effects on Anxiety at Work and at

Home”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 38, No. 4, Pp.

1105–1123.

U.R. Dumdum, K.B. Lowe & B.J. Avolio (2002), “A MetaAnalysis of Transformational and Transactional Leadership

Correlates of Effectiveness and Satisfaction: An Update and

Extension”, Editors: B.J. Avolio & F.J. Yammarino,

“Transformational Leadership and Charismatic Leadership:

The Road Ahead”, Vol. 2. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Science, Pp.

35–66.

L. Eby, D. Adams, J. Russell & S. Gaby (2000), “Perceptions

of Organizational Readiness for Change: Factors related to

Employee's Reactions to the Implementation of Team-based

Selling”, Human Relations, Vol. 53, No. 3, Pp. 419–428.

ISSN: 2321-242X

[18]

[19]

[20]

[21]

[22]

[23]

[24]

[25]

[26]

[27]

[28]

[29]

[30]

[31]

[32]

[33]

[34]

[35]

R. Eisenberger, S. Armeli, B. Rexwinkel, P.D. Lynch & L.

Rhoades (2001), “Reciprocation of Perceived Organizational

Support”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 86, No. 1, Pp.

42–51.

R. Eisenberger, P. Fasolo & V. David-LaMastro (1990),

“Perceived Organizational Support and Employee Deligence,

Commitment, and Innovation”, Journal of Applied Psychology,

Vol. 75, Pp. 51–59.

R. Eisenberger, F. Stinglhamber, C. Vandenberghe, I.L.

Sucharski & L. Rhoades (2002), “Perceived Supervisor

Support: Contributions to Perceived Organizational Support

and Employee Retention”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol.

87, No. 3, Pp. 565–573.

J.L. Farh, P.C. Earley & S.C. Lin (1997), “A Cultural Analysis

of Justice and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Chinese

Society”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 42, Pp. 421–

444.

D.B. Fedor, S. Caldwell & D.M. Herold (2006), “The Effects

of Organizational Changes on Employee Commitment: A

Multilevel Investigation”, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 59, Pp.

1–19.

C.R. Fornell & D.F. Larcker (1981), “Structural Equation

Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error”,

Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18, No. 3, Pp. 39–50.

C. Glisson & M. Durick (1988), “Predictors of Job Satisfaction

and Organization Commitment”, Administrative Science

Quarterly, Vol. 33, No. 1, Pp. 61–81.

A.W. Gouldner (1960), “The Norm of Reciprocity: A

Preliminary Statement”, American Sociological Review, Vol.

25, No. 2, Pp. 161–178.

M.A. Griffin, M.G. Patterson & M.A. West (2001), “Job

Satisfaction and Teamwork: The Role of Supervisor Support”,

Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 22, Pp. 537–550.

D. Guest (1987), “Human Resource Management and Industrial

Relations”, Journal of Mamagement Studies, Vol. 24, No. 5,

Pp. 503–521.

J.J.F. Hair, R. Anderson, R.L. Tatham & W.C. Black (2006),

“Multivariate Data Analysis (6th Ed.)”, Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice Hall International Editions.

D.M. Herold, D.M. Fedor & S.D. Caldwell (2007), “Beyond

Change Management: A Multilevel Investigation of Contextual

and Personal Influences on Employees' Commitment to

Change”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 92, No. 4, Pp.

942–951.

D.M. Herold, D.B. Fedor, S.D. Caldwell & Y. Liu (2008), “The

Effects of Transformational Leadership and Change Leadership

on Employees' Commitment to a Change”, Journal of Applied

Psychology, Vol. 93, No. 2, Pp. 346–357.

L. Herscovitch & J.P. Meyer (2002), “Commitment to

Organizational Change: Extension of a Three-Component

Model”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 87, No. 3, Pp.

474–487.

M.J. Higgs & D. Rowland (2000), “Building Change

Leadership Capability: The Quest for Change Competence”,

Journal of change management, Vol. 1, No. 2, Pp. 116–131.

R.D. Iverson (1996), “Employee Acceptance of Organizational

Change: The Role of Organizational Commitment”, The

international Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 7,

No. 1, Pp. 122–149.

S. Jaros (2010), “Commitment to Organizational Change: A

Critical Review”, Journal of Change Management, Vol. 10,

No. 1, Pp. 79–108.

K. Jaskyte (2003), “Assessing Changes in Employees’

Perceptions of Leadership Behavior, Job Design, and

Organizational Arrangements and their Job Satisfaction and

© 2015 | Published by The Standard International Journals (The SIJ)

7

The SIJ Transactions on Industrial, Financial & Business Management (IFBM), Vol. 3, No. 1, January 2015

[36]

[37]

[38]

[39]

[40]

[41]

[42]

[43]

[44]

[45]

[46]

[47]

[48]

[49]

[50]

[51]

[52]

Commitment”, Administration in Social Work, Vol. 27, No. 4,

Pp. 25–39.

N.L. Jimmieson, D.J. Terry & V.J. Callan (2004), “A

Longitudinal Study of Employee Adaptation to Organizational

Change: The Role of Change-related Information and Changerelated Self-efficacy”, Journal of Occupational Health

Psychology, Vol. 9, No. 1, Pp. 11–27.

T.A. Judge & J.E. Bono (2000). “Five-factor Model of

Personality and Transformational Leadership”, Journal of

Applied Psychology, Vol. 85, No. 5, Pp. 751–765.

T.A. Judge, C.J. Thoresen, V. Pucik & T.M. Welbourne (1999),

“Managerial Coping with Organizational Change: A

Dispositional Perspective”, Journal of Applied Psychology,

Vol. 84, No. 1, Pp. 107–122.

N.F. Krueger & P.R. Dickson (1993), “Perceived Self-efficacy

and Perceptions of Opportunity and Threat”, Psychological

Report, Vol. 72, Pp. 1235–1240.

E. Lamm & J.R. Gordon (2010), “Empowerment,

Predisposition to Resist Change, and Support for

Organizational Change”, Journal of Leadership &

Organizational Studies, Vol. 17, No. 4, Pp. 426–437.

C.M. Lau & R.W. Woodman (1995), “Understanding

Organizational Change: A Schematic Perspective”, Academy of

Management Journal, Vol. 38, No. 2, Pp. 537–554.

C.R. Leana & B. Barry (2000), “Stability and Change as

Simultaneous Experiences in Organizational Life”, Academy of

Management Review, Vol. 25, No. 4, Pp. 753–759.

H. Levinson (1965), “Reciprocation: The Relationship between

Man and Organization”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol.

9, No. 4, Pp. 370–390.

E.A. Lind., T.R. Tyler & Y.J. Huo (1997), “Procedural Context

and Culture: Variation in the Antecedents of Procedural Justice

Judgments”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

Vol. 73, No. 4, Pp. 767–780.

M.D. Litt (1988), “Cognitive Mediators of Stressful

Experience: Self-efficacy and Perceived Control”, Cognitive

Theory and Research, Vol. 12, No. 3, Pp. 241–260.

R.M. Malatesta (1995), “Understanding the Dynamics of

Organizational and Supervisory Commitment using a Social

Exchange Framework”, Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation,

Wayne State University, Detroit, MI.

J.E. Mathieu & D.M. Zajac (1990), “A Review and MetaAnalysis of the Antecedents, Correlates and Consequence of

Organizational Commitment”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol.

108, No. 2, Pp. 171–194.

J.P. Meyer & L. Herscovitch (2001). “Commitment in the

Workplace toward a General Model”, Human Resource

Management Review, Vol. 11, Pp. 299–326.

J.P. Meyer, E.S. Srinivas, J.B. Lai & L. Topolnytsky (2007),

“Employee Commitment and Support for an Organizational

Change: Test of the Three-Component Model in Tow Culture”,

Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Vol.

80, No. 2, Pp. 185–211.

V.D. Miller, J.R. Johnson & J. Grau (1994), “Antecedents to

Willingness to Participate in a Planned Organizational

Change”, Journal of Applied Communication Research, Vol.

22, Pp. 59–80.

J.T. Parish, S. Cadwallader & P. Busch (2007), “Want, Need

to, Ought to: Employee Commitment to Organizational

Change”, Journal of Organizational Change Management, Vol.

21, No. 1, Pp. 32–52.

P.M. Podsakoff, S.B. MacJenzie, R.H. Moorman & R. Fetter

(1990), “Transformational Leader Behaviors and their Effects

ISSN: 2321-242X

on Followers’ Trust in Leader, Satisfaction, and Organizational

Citizenship Behaviors”, Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 2,

Pp. 107–142.

[53] P.M. Podsakoff, S.B. MacKenzie, J.Y. Lee & N.P. Podsakoff

(2003), “Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A

Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended

Remedies”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 88, Pp. 879–

903.

[54] G.E. Prussia, J.S. Anderson & C.C. Manz (1998), “SelfLeadership and Performance Outcomes: The Mediating

Influence of Self-efficacy”, Journal of Organizaitonal

Behavior, Vol. 19, Pp. 523–538.

[55] J. Schaubroeck & D.E. Merritt (1997), “Divergent Effects of

Job Control on Coping with Work Stressors: The Key Role of

Self-efficacy”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 40, No.

3, Pp. 738–754.

[56] R. Schwarzer, J. Bäßler, P. Kwiatek, K. Schröder & J.X. Zhang

(1997), “The Assessment of Optimistic Self-beliefs:

Comparison of the German, Spanish, and Chinese Versions of

the General Self-Efficacy Scale”, Applied Psychology, Vol. 46,

No. 1, Pp. 69–88.

[57] B. Schyns (2004), “The Influence of Occupational Self-efficacy

on the Relationship of Leadership Behavior and Preparedness

for Occupational Change”, Journal of Career Development,

Vol. 30, No. 4, Pp. 247–261.

[58] M. Vakola & I. Nikolaou (2005), “Attitudes toward

Organizational Change - What is the Role of Employees' Stress

and Commitment?”, Employee Relation, Vol. 27, No. 2, Pp.

160–174.

[59] N.W. van Yperen & M. Hagedoorn (2003), “Do High Job

Demands Increase Intrinsic Motivation or Fatigue or Both? The

Role of Job Control and Job Social Support”, Academy of

Management Journal, Vol. 46, No. 3, Pp. 339–348.

[60] C.R. Wanberg & J.T. Banas (2000), “Predicators and Outcomes

of Openness to Changes in a Reorganizing Workplace”,

Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 85, No. 1, Pp. 132–142.

[61] S.J. Wayne, L.M. Shore & R.C. Liden (1997). “Perceived

Organizational Support and Leader-Member Exchange: A

Social Exchange Perspective”, Academy of Management

Journal, Vol. 40, No. 1, Pp. 82–111.

[62] R. Wood & A. Bandura (1989), “Social Cognitive Theory of

Organizational Management”, The Academy of Management

Review, Vol. 14, No. 3, Pp. 361–383.

Paul Chou earned his Ph.D. degree in human resource management

from the School of Management, National Central University,

Taiwan in 2007. Before enrolling in the Ph.D. program, he had

worked as an HR practitioner for 28 years in several multinational

companies in Taiwan. His current research interests are strategic

human resource management and organizational change

management. His published works are:

1. The HR Competencies-HR effectiveness Link: A Study in

Taiwanese High-Tech companies. Human Resource

management (2006), 45(3), Pp. 391-404.

2. The Effect of Transformational Leadership on Follower’s

Affective Commitment to Change. World Journal of Social

Science (2013), 1(3), Pp. 38-52.

3. Transformational Leadership and Employee’s Behavioral

Support to Organizational Change. Management and

Administrative Sciences Review (2014), 3(6), Pp.825-838.

4. Does

Transformational

Leadership

matter

during

Organizational Change? European Journal of Sustainable

Development (2014), 3(3), Pp.49-62.

© 2015 | Published by The Standard International Journals (The SIJ)

8