Network Brokerage: How the Social Network Around You Creates Competitive Advantage

advertisement

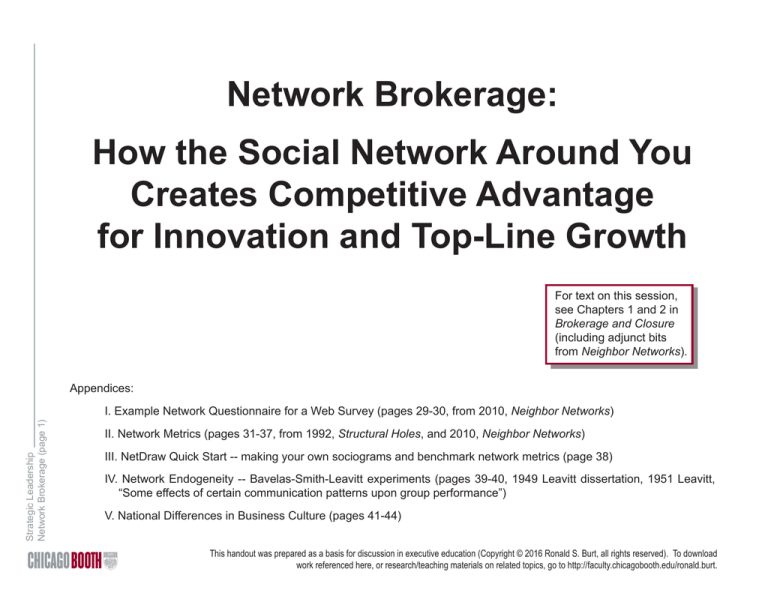

Network Brokerage: How the Social Network Around You Creates Competitive Advantage for Innovation and Top-Line Growth For text on this session, see Chapters 1 and 2 in Brokerage and Closure (including adjunct bits from Neighbor Networks). Appendices: Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 1) I. Example Network Questionnaire for a Web Survey (pages 29-30, from 2010, Neighbor Networks) II. Network Metrics (pages 31-37, from 1992, Structural Holes, and 2010, Neighbor Networks) III. NetDraw Quick Start -- making your own sociograms and benchmark network metrics (page 38) IV. Network Endogeneity -- Bavelas-Smith-Leavitt experiments (pages 39-40, 1949 Leavitt dissertation, 1951 Leavitt, “Some effects of certain communication patterns upon group performance”) V. National Differences in Business Culture (pages 41-44) This handout was prepared as a basis for discussion in executive education (Copyright © 2016 Ronald S. Burt, all rights reserved). To download work referenced here, or research/teaching materials on related topics, go to http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/ronald.burt. Sociogram of the Org Chart for a Large EU Healthcare Organization CEO C-Suite Heir Apparent Other, Respondent Other, NonRespondent Bill Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 2) Bob Figure 1.1 in Burt (2017, Structural Holes in Virtual Worlds). Sociogram of Senior Leadership in the Healthcare Organization Asia US Lines indicate frequent and substantive work discussion; heavy lines especially close relationships. Bill EU and Emerging Markets Bob B Front Office B B B Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 3) B B CEO C-Suite Heir Apparent Back Office B R&D Other Senior Person Figure 1.2 in Burt (2017, Structural Holes in Virtual Worlds). Coordination across groups is the source of competitive advantage from social networks — an advantage often difficult to realize, as illustrated by the below opinions from a senior executive education program. The difficulty most often cited as needing to be improved: Coordination across groups. SURVEY QUESTION: Every person in the [company] program has a perspective on [company] operations and clients. Drawing on your experience, what would you like to see changed within [the company] to increase the company's current value as a provider of high-quality, effective, attractive service to clients? RESPONSES: At least two-thirds of responses are variations on "improve coordination across groups." For example (idea ratings are based on independent pile-sort evaluations by the head of HR and a regional P&L leader): HIGH RATED: We need a "DNA" change - we are so deeply ingrained in the P&L, near-term financial results mindset that we limit our potential for changing the world. It goes beyond P&L reporting or annual goals - we need more people talking and thinking and acting and making decisions that are focused on one voice, delivering for clients and colleagues. We are not a "clients first" firm we say we are, but we are not. We are a Wall Street/investor first firm. Need to change that. Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 4) HIGH RATED: (1) Improve team work in global network. Global clients want to see us acting more as one team (e.g. global P&L for TOP Global clients). (2) Better understanding of capabilities and solutions of other business units, and improving colleague network cross business units (one voice). (3) Best practice sharing cross countries, esp. for same roles/job titles to copy/paste success stories and solutions for our clients. (4) Improve incentive/bonus structure to drive x-Selling (in country between BUs, also globally within BUs). (5) Better understanding of [company]'s global capabilities and whom to talk to for a special solution. HIGH RATED: (1) “One Client View." Ability to easily understand [company]-wide relationships with any client or prospect in the world. Comprehensive, single instance client account data system. Ability to pull up information on a client (any business unit) from one system. Data should include: revenue, oppty amount, current solutions provided, account owner(s), history of account, etc. (2) Connect the dots between business initiatives and commitments, and finance/budget. When the business makes commitments to do something, sometimes we need to do a better job at ensuring those commitments are resourced appropriately (otherwise we end up with frustrated and over-worked colleagues with compensation not commensurate with their scope and/or efforts). ILLUSTRATIVE RELATED IDEAS: - More coordination among different parts of the company. A better understanding of each other's business and the value it brings to clients. A clearer internal structure that allows us to deliver to clients the best of [company] with internal P&L driven issues. - Continue to endeavor to remove our P&Ls as barriers to cross-practice collaboration. - A far more joined-up [company]. We don't speak to client yet routinely about our true capability across [company]. We are moving in that direction, but this would be a genuine game changer and add material value. Not a new idea I know! - Better integrated client management activities across the operating groups. - Find an easier way to work across businesses and geographies to really bring the best of [company] to all clients. To begin, the "network" around a person is a pattern of relationships with and between colleagues. This worksheet is completed in four steps: (1) In the oval, write the name of a significant colleague. The colleague could be your most valuable subordinate, your most difficult, your boss, an important source of support, or a key contact in another organization. Who doesn't matter. It just has to be someone you know well enough to know their key contacts. (2) In the squares, write the name of the five contacts with whom the person in the oval has the most frequent and substantial business contact. Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 5) (3) Draw a line between any pair of contacts that are connected in the sense that the two people speak often enough that they have some familiarity with current issues in one another's work. (4) Compute network density. Count the number of lines between contacts (TIES). Divide by the number possible (n[n-1]/2, where n is the number of contacts, which is 5 if you entered five contacts). Multiply by 100 and round to nearest percent. DENSITY = _____________ Appendix I contains an illustrative survey webpage used to gather network data. SOCIOGRAM graphic image of a network in which dots represent nodes (a person, group, etc.) and lines represent connections Social Capital of Brokerage 2.5 Manifest as better ideas, more-positive evaluations, higher compensation, earlier promotion, and faster teams. Z-Score Relative Performance (compensation, evaluation, promotion) 2.0 Now, establish the empirical fact that the people we will discuss as "network brokers" enjoy achievement and rewards higher than their peers. Brokers are distinguished on the horizontal axis. 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 -0.5 -1.0 -1.5 Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 6) -2.0 -2.5 5 15 25 35 45 55 65 75 85 95 Network Constraint (C) large, open many ——— Structural Holes ——— few Circles are average z-score performance (Z) for a five-point interval of network constraint Robert (C) within each of eight study populations. Dashed line goes through mean values of Z for intervals of C. Bold line is performance predicted by the natural log of C. small, closed James From Figure 1.8 in Brokerage and Closure. Data pooled across eight study-population graphs in Appendix II on measuring network constraint. E (compensation, evaluation, promotion) Z-Score Relative Performance E 1.5 E 1.0 J E 0.5 E median network constraint (35 points) E E E performance E E EE lower than E E E EE E E E E expected E E E E E E E E E J J E J J E J JE E J E J E E E E E J E J E J J E E Human Capital et Eal. E EEgeography, kind of work, division, education, etc.) EE (e.g., job rank, age, E E E E E E E E E 0.0 -0.5 -1.0 -1.5 -2.5 E performance than more-positive evaluations, higher compensation, Manifest as higher better ideas, expected earlier promotion, and faster teams. E E J E EE E JE E E EE E J E E E E E E E E E J E EE E E E E E E J E EE E -2.0 Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 7) Performance Indicator E 2.0 (compensation, evaluation, promotion rate) 2.5 Social Capital of Brokerage E E E E 5 15 25 35 E 45 55 65 75 Z = 2.78 - .82 ln(C) r = -.53 85 95 Achievement and rewards are distinguished on the vertical axis, measuring the extent to which a person is doing better than his or her peers. Network Constraint (C) large, open many ——— Structural Holes ——— few Circles are average z-score performance (Z) for a five-point interval of network constraint Robert (C) within each of eight study populations. Dashed line goes through mean values of Z for intervals of C. Bold line is performance predicted by the natural log of C. small, closed James From Figure 1.8 in Brokerage and Closure. Data pooled across eight study-population graphs in Appendix II on measuring network constraint. Social Capital of Brokerage 2.5 Manifest as better ideas, more-positive evaluations, higher compensation, earlier promotion, and faster teams. E (compensation, evaluation, promotion) Z-Score Relative Performance Brokerage is a large percentage of explained performance differences. E 2.0 E 1.5 E 1.0 E E J E E E J E EE E JE E E E EE E J E E E E E E E E E J E E EE E E E E E E EJ E EE 0.5 0.0 -0.5 E E E EE E E E E E E E E J E J J E E E EE EE -1.5 E E E E E E E E J J E E 17% EE J E E J E E J J E E E EE J J E E 9% E E E E E E 5 15 25 35 E 45 55 E E 81% 65 75 Z = 2.78 - .82 ln(C) r = -.53 85 95 Network Constraint (C) large, open 10% E J E E -2.0 Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 8) E E -1.0 -2.5 E 55% 28% median network constraint (35 points) many ——— Structural Holes ——— few Circles are average z-score performance (Z) for a five-point interval of network constraint Robert (C) within each of eight study populations. Dashed line goes through mean values of Z for intervals of C. Bold line is performance predicted by the natural log of C. 33% 2% small, closed James 64% Brokerage Contributes "Slightly More than Half" of Predicted Variance in Performance Differences between Managers: Network constraint (white), job rank (red), and other factors (striped). First pie is investment banker compensation and analyst election to the All-America Research Team. Second pie is supply-chain and HR manager compensation in corporate bureaucracies. Third pie is early promotion to senior job rank in a large electronics firm. Graph is from Figure 1.8 in Brokerage and Closure. Data are pooled across eight management populations. Pie charts are from Figure 2.4 in Neighbor Networks. On causal order, see Appendix IV. Returns to Brokerage Aggregate to Companies, Industries, and Communities People with phone networks that span structural holes live in communities higher in socio-economic rank Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 9) Networks are defined by land-line & mobile phone calls (map to left). Socio-economic rank is UK government index of multiple deprivation (IMD) based on local income, employment, education, health, crime, housing, and environmental quality (graph below). Units are phone area codes. figures from Eagle, Macy, and Claxton (2010, Science), “Network diversity and economic development” Returns to Brokerage Are Evident in Low Returns to Pre-Job Specialization Recent scholarship on the returns to labor market specialization often claims that being specialized is advantageous for job candidates. We argue, in contrast, that a specialist discount may occur in contexts that share three features: strong institutionalized mechanisms, candidate profiles with direct investments that signal their value, and a high supply of focused candidates relative to demand. We then test whether there is a specialist discount for graduating elite MBAs, as it is a labor market that exemplifies these conditions under which we expect specialists to be penalized. Using rich data on two graduating cohorts from a toptier U.S. business school (full-time students, 2008-2009), we show that elite MBA graduates who established a focused (specialized) market profile of experiences relating to investment banking before and during the program were less likely to receive multiple job offers and were offered less in starting-bonus compensation than similar MBA candidates with no exposure or less-focused exposure to investment banking. Our theory and findings suggest that the oft-documented specialist advantage may be overstated. Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 10) Figure 1 displays predicted (marginal) probabilities of receiving multiple offers for candidates who have mean values for each of the control variables but different profiles. Figure 2 compares the starting bonuses of hypothetical job candidates with different profiles. Each hypothetical candidate is a single white male who graduated from a top-20 undergraduate institution, has above a 3.8 GPA, received more than one job offer, has the mean age and work experience characteristics (months, number of firms), accepts a job in I-banking, and earns the mean base salary for I-banking jobs in his 2008 cohort year. The only difference is the candidate’s profile in terms of exposure to I-banking. FOCUSED (career history in finance before mba, concentration in finance, joined an i-banking club during mba, and i-banking internship; 61% of students who graduate to a job in i-banking were focused on i-banking) NON-SEQUENTIAL exposure (neither of the above categories, but some mba program contact with i-banking) PARTIAL sequential exposure (prior experience in finance + concentration in finance or participation in i-banking club) PRE-MBA exposure (only exposure before mba program) figures and text from Merluzzi and Phillips (2016, Administrative Science Quarterly), “The Specialist Discount," and for more applied discussion, see Merluzzi, (June 2016, HBR), "Generalists get better job offers than specialists." Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 11) Second Life prediction from constrained social network Second Life prediction from nonredundant social contacts EverQuest II prediction from nonredundant social (upper) versus economic (lower) contacts EverQuest II prediction from constrained social (upper) versus economic (lower) network 25+ Effective Size (Number of NonRedundant Contacts) Network Constraint (x 100) This is Figure 3.5 in Burt, Structural Holes in Virtual Worlds (2017). Dots are average Y scores within integer (left) or five-point (right) intervals on horizontal axis. EverQuest II achievement variable is the predicted character level in Model 8, Tables 3.4 and 3.5. Second Life achievement is the canonical correlation dependent variable in Model 15, Tables 3.5 and 3.6 (associations with individual achievement dimensions in Second Life are given in graphs in Appendix V). Predicted Avatar Z-score Achievement Predicted Avatar Z-score Achievement Returns to Brokerage Are Evident Online in the Network-Achievement Connection within Virtual Worlds And the Network Brokerage Effect Is Evident in Coordination between Organizations Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 12) Supplier Evaluation of Telecom (mean eval of forecast accuracy and development cycle volatilty) (1 = unacceptable, 2 = satisfactory, 3 = meets requirement Supplier evaluation: Leaders in 32 key supplier organizations were interviewed about their experience with a leading American telecom ("the company"). For larger suppliers, two or three agents were interviewed (e.g., Foxconn, Samsung, Sharp, Toshiba). The agents were asked to describe their experience with respect to company forecast accuracy and volatility in the company's development cycle (3 meets requirements, 2 satisfactory, or 1 unacceptable). The vertical axis is the average evaluation of the telecom company from each key supplier. r = -.44 t = -2.89 P < .01 Network Constraint on Best-Connected Procurement Manager Assigned to the Supplier (lowest network constraint score among managers for whom the supplier is where manager spends the most time) Supplier POC in telecom: The 55 managers in procurement support (no direct supplier contact) were asked to indicate their involvement in company operations with each of the 32 key suppliers. A manager could say that a supplier is one "on which I spend the most time," or "with which I have some direct contact," or "on which I work indirectly through other motorola employees" (or leave it blank if respondent had no contact with the supplier). For each of the 32 key suppliers, I identified the respondents who said they spend "most time" on the supplier, and selected the two respondents who had the most attractive network metrics defined by "frequent and substantive work contact" relations. The horizontal axis is the average network constraint score for the two best-connected procurement managers spending "most time" on the supplier providing the evaluation on the vertical axis. HOW IT WORKS: Recombinant Sticky Information Contacts as Source vs. Portal YOU YOU YOU Network A Network B Network C Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 13) Redundancy by Cohesion YOU A Contact Redundancy 1 B 7 2 3 James Robert Redundancy by Structural Equivalence 5 YOU 4 6 C&D Network Constraint (C = Σj cij = Σj [pij + Σq piqpqj]2, i,j ≠ q) 85 Density Table 5 25 0 1 100 0 0 29 Group A Group B Group C 0 Group D person 3: .402 = [.25+0]2 + [.25+.084]2 + [.25+.091]2 + [.25+.084]2 Robert: .148 = [.077+0]2 + [.154+0]2 + [.154+0]2 + [.154+0]2 + [.154+0]2 + [.154+0]2 + [.154+0]2 from Figures 1.1 and 1.3 in Burt (1992, Structural Holes) and Figure 1.2 in Brokerage and Closure Bridge & Cluster: Small World of Organizations & Markets A 1 B 7 2 3 James Robert 5 4 Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 14) 6 C&D Network Constraint (C = Σj cij = Σj [pij + Σq piqpqj]2, i,j ≠ q) 85 Density Table 5 25 0 1 100 0 0 29 Group A Group B Group C 0 Group D person 3: .402 = [.25+0]2 + [.25+.084]2 + [.25+.091]2 + [.25+.084]2 Robert: .148 = [.077+0]2 + [.154+0]2 + [.154+0]2 + [.154+0]2 + [.154+0]2 + [.154+0]2 + [.154+0]2 Network indicates distribution of sticky information, which defines advantage. From Figure 1.1 in Brokerage and Closure. For an HBR treatment of the network distinction between Robert and James, see in the course packet Kotter's classic distinction between "leaders" versus "managers." Robert ideally corresponds to the image of a "T-shaped manager," nicely articulated in Hansen's HBR paper in the course packet. Here is the core network for a job BEFORE and AFTER the employee expanded the social capital of the job by reallocating network time and energy to more diverse contacts. Create Value by Bridging Structural Holes It is the weak contact connections (structural holes) in the AFTER network that provides the expanded social capital. 1 2 STRUCTURAL HOLE disconnection between two groups or clusters of people Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 15) BRIDGE relation across structural hole NETWORK ENTREPRENEUR or "broker," or "connector:" a person who coordinates across a structural hole BROKERAGE act of coordinating across a structural hole 4 5 .6 con s t rai nt STICKY INFORMATION Information expensive to move because: (a) tacit, (b) complex, (c) requires other knowledge to absorb, or (d) interaction with sender, recipient, or channel. 53 BEFORE 3 The employee AFTER is more positioned at the crossroads of communication between social clusters within the firm and its market, and so is better positioned to craft projects and policy that add value across clusters. Research shows that employees in networks like the AFTER network, spanning structural holes, are the key to integrating 20 operations across functional .0 and business boundaries. In co ns tra research comparing senior people int * with networks like these BEFORE and AFTER networks, it is the AFTER networks that are associated with more creativity, faster learning, more positive individual and team evaluations, faster promotions, and higher earnings. information breadth, timing, and arbitrage 1 2 AFTER *Network scores refer to direct contacts. From Figure 1.4 in Burt (1992, Structural Holes) and Figure 1.2 in Brokerage and Closure. See Appendix I on survey network data, Appendix II on measuring network constraint. 3 4 5 Illustrative Networks around Early and Late Adopters of the Chinese Social Media Service Weibo Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 16) Sociograms show connections among the people and organizations a user follows. The network around the early adopter reveals a broker across three social clusters. In comparison, the late adopter is embedded in a single closed network. Released in 2009, following suppression of western microblogging services such as Twitter, Facebook, Plurk and Fanfou, Weibo is a social media service that combines elements of Twitter and Facebook. It is one of the largest such services in the world (over half a billion users at the end of 2012). Figures are from Burt, Huang, Tang, and Zhang, "Sampling Weibo" (2016). Guangdong Late User This is a male 9.90 months in Weibo posting 1,916 messages and following 81 others during the observation period (73.0 nonredundant contacts, 10% mutual contacts, 1 early adopter, 79% in Guangdong, 67% celebrities, 13.6% network density among contacts (50% mutual), 4.5 constraint from contacts, 1,774.1 betweenness). Symbols are people the user followed during the observation period (10 additions during the period). Circles are contacts who also live in Guangdong. Squares are contacts who live elsewhere. Larger symbols are contacts with whom the user has a mutual relationship (each follows the other). Lines indicate connections between the user’s contacts. Heavy lines indicate mutual relations. Thin lines indicate ties in which only one follows the other. Symbols are people the user followed during the observation period (7 changed during the period). Circles are contacts who also live in Guangdong. Squares are contacts who live elsewhere. Larger symbols are contacts with whom the user has a mutual relationship (each follows the other). Lines indicate connections between the user’s contacts. Heavy lines indicate mutual relations. Thin lines indicate connections in which only one contact follows the other. Common user (10) Star user (15) Celebrity user (54) Organization user (2) Common user (10) Star user (15) Celebrity user (54) Organization user (2) Guangdong Early User This is a male 32.93 months in Weibo, posting 3,805 messages, and following 198 contacts during the observation period (187.5 nonredundant contacts, 13% mutual, 11 early adopters, 17% Guangdong, 20% celebrities, 8.3% density (22% mutual), 2.3 constraint, 9,742.4 betweenness). HOW IT WORKS: Creativity and Innovation Are at the Heart of It Achievement & Rewards (What benefits?) Brokerage across Structural Holes What in your work improves the odds (How to frame it & who should be involved?) that you will discover the value of something you don't know you don't know? Adaptive Implementation Creativity & Innovation Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 17) (What should be done?) Alternative Perspective (how would this problem look from the perspective of a different group, or groups — thinking “out of the box” is often less valuable than seeing the problem as it would look if you were inside a specific “other box”) Best Practice (something they think or do could be valuable in my operations) Analogy (something about the way they think or behave has implications for how I can enhance the value of my operations; i.e., look for the value of juxtapositioning two clusters, not reasons why the two are different so as to be irrelevant to one another — you often find what you look for) Synergy (resources in our separate operations can be combined to create a valuable new idea/practice/product) from Burt, "The social capital of structural holes" (2002, The New Economic Sociology). The consequences of the information diversity associated with network brokerage is productively elaborated at length in economist Scott Page's 2007 book, The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools and Societies. Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 18) FIRST CAUTION: Returns to network brokerage are a probability, not a certainty. Access to structural holes merely "increases the risk of productive accident." Patent co-authoring network from Lee Fleming & Matt Marx, "Managing creativity from Brice Belisle, "Pet display clothing" From Fleming & Marx, "Managing creativity in small worlds" (California Management Review, 2006) in small worlds" (California Management Review, 2006; see Fleming et al. 2007 ASQ). (US Patent 5,901,666 granted May 11, 1999). Advantage from Varied Perspectives: Information arbitrage is Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 19) about framing as much as content. Problem vs. Paradox.* What point of view, or frame of reference, will make my idea attractive? The key is not to get "out of the box," so much as to see from within a different box.* Failure here could be a good idea over there. Carl Segerstrom, in Chicago’s 2012 ADP, worked at Pfizer when the Viagra trials were run. Carl sketched the story: Trials showed that the new drug was a failure as a heart medicine, so the trials were shut down and the test samples were recalled. Subjects were asked to return the test samples, and they usually do, but in this case, an unusually high proportion of subjects did not return the test samples. Someone asked, “let’s find out why they aren’t returning the test samples,” which revealed the profitable side-effect. Originally, minoxidil was used exclusively as an oral drug (with the trade name ‘Loniten’) to treat high blood pressure. However, it was discovered to have an interesting side effect: hair growth. Minoxidil may cause increased growth or darkening of fine body hairs, or in some cases, significant hair growth. When the medication is discontinued, the hair loss will return to normal rate within 30 to 60 days. *The "problem vs. paradox" point is nicely elaborated by David Doltish, Peter Cairo, and Cade Cowan in The Unfinished Leader (2014). The "out of the box" point is nicely elaborated by Luc de Brabandere (2005), The Forgotten Half of Change: Achieving Greater Creativity through Changes in Perception. See IDEO on the saying "fail often to succeed sooner," Stuart Firestein (2016) Failure, on the critical role failure plays in successful science, and Ludwik Fleck (1979) Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact, on the critical role that proto-ideas play in successful science. In short, network brokerage is a process by which people clear sticky-information markets. The rewards enjoyed by network brokers are compensation for clearing a market that would otherwise not clear. Therefore, variation between clusters/silos is essential to the value of brokerage. If there are no information differences between social clusters, then there is no value to moving information from one cluster to another. Competition in open markets explicitly eliminates variation, though social clustering in networks usually indicates variation in understanding and practice. For example, BP learning in the refining businesses. Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 20) Strong belief/culture/process/paradigm reinforce closed networks, and can obscure or blind people to variation between subgroups within the network. For example: — Pfizer drug trial protocol — Talent out of context (able musician in D.C. metro train station) — INSEAD student teams — Coca Cola as a distribution company versus custodian of the Coca Cola brand — "Hard" sciences & the negative correlation between age and contribution look for use of right-wrong versus productive-unproductive or interesting-uninteresting Personal experience is perhaps the most insidious blinder. Personal experience enriches understanding, but it can also limit understanding. Many people are trapped in their limited personal experience. They only hear/believe/understand knowledge consistent with what they’ve already experienced. The power of understanding fundamental principles, and being able to re-frame problems in different ways, is that you can reason your way through challenges that involve experiences you have not yet had — making you valuable beyond whatever experience life has happened to give you personally. Even within Frame, Are You Thinking about the Work Productively? Modularity increases the risk of productive accident. Netscape’s Navigator was released under open-source license in March 1998 as Mozilla. It was re-designed for modularity to make it more attractive to contributors. Networks below show module dependencies before and after the re-design. ”Propagation cost” is the average percentage of code that must be updated following a change in any one module. Mozilla version 1998-04-08 Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 21) propagation cost:* 17.35% Longitudinal Evolution of Mozilla Propagation Cost* Mozilla version 1998-12-11 propagation cost: 2.78% From MacCormack, Rusnak,and Baldwin, “Exploring the structure of complex software designs” (2006, Management Science). For broad discussion of modularity in high tech, see Baldwin and Clark, Design Rules: The Power of Modularity, 2000, MIT press. And Social Context: Where did US time zones come from? Until 1883 each United States railroad chose its own time standards. The Pennsylvania Railroad used the "Allegheny Time" system. By 1870 the Allegheny Time service extended over 2,500 miles with 300 telegraph offices receiving time signals. However, almost all railroads out of New York ran on New York time, and railroads west from Chicago mostly used Chicago time, but between Chicago and Pittsburgh/Buffalo the norm was Columbus time, even on railroads which did not run through Columbus. The Northern Pacific Railroad had seven time zones between St. Paul and the 1883 west end of the railroad at Wallula Junction. Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 22) In 1870 Charles F. Dowd proposed four time zones based on the meridian through Washington, DC for North American railroads. In 1872 he revised his proposal to base it on the Greenwich meridian. Sandford Fleming, a Canadian, proposed worldwide Standard Time at a meeting of the Royal Canadian Institute on February 8, 1879. Cleveland Abbe advocated standard time to better coordinate international weather observations and resultant weather forecasts, which had been coordinated using local solar time. In 1879 he recommended four time zones across the contiguous United States, based upon Greenwich Mean Time. The General Time Convention (renamed the American Railway Association in 1891), an organization of US railroads charged with coordinating schedules and operating standards, became increasingly concerned that if the US government adopted a standard time scheme it would be disadvantageous to its member railroads. William F. Allen, the Convention secretary, argued that North American railroads should adopt a five-zone standard, similar to the one in use today, to avoid government action. On October 11, 1883, the heads of the major railroads met in Chicago at the Grand Pacific Hotel and agreed to adopt Allen's proposed system. ... Standard time was not enacted into US law until the 1918 Standard Time Act.* *Text comes from October 24, 2015 Wikipedia entry for "Standard time" (five zones include one east of Eastern zone). Map is Dowd's 1884 fifth version advocating to railroaders the adoption of standard time zones. Engraving of William Allen is from Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly (April 1884). For details on bureaucratic infighting over standard time, see Bartky, Selling the True Time (2000, Stanford University Press). Illustration: Where did the M-16 come from? Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 23) Discussion Question* Consequential ideas are typically attributed to special people, geniuses, in part to make us feel less uncomfortable about our own ideas. True to form, an American armament expert describes Eugene Stoner, the engineer who developed the M-16 assault rifle, as "an engineering genius of the first order." Another describes him as "the most gifted small-arm designer since Browning." (Browning patented the widely-adopted BAR and 45 automatic.) 1. Based on the brief history video, how would you describe Stoner's genius? 2. What circumstances might allow you or your colleagues to be as creative? *Photos are from the video shown during the session. For discussion and references, see page 73 in Brokerage and Closure. For sampling on the dependent variable, see Rosenzweig, “Misunderstanding the nature of company performance: the halo effect and other business delusions,” 2007 California Management Review. Average Z-Score Idea Value Average Z-Score Idea Value More Generally: Network Brokers Propose Better Ideas A. Good ideas are associated with many nonredundant contacts 2 (R = .89, n = 39, t = 12.05, -7.44) B. Good ideas are associated with large, open networks (R2 = .64, n = 54, t = -9.67) Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 24) 12+ NonRedundant Contacts few ——— Structural Holes ——— many Network Constraint many ——— Structural Holes ——— few Graphs show idea quality increasing with more access to structural holes in the networks around supply-chain managers in a large electronics firm. Circles in graph A are average scores on the vertical axis within interval numbers of nonredundant contacts. Circles in graph B are average scores on the vertical axis for five-point intervals of network constraint. Bold line is the vertical axis predicted by a function of nonredundant contacts (graph A, linear and squared terms), or the natural logarithm of network constraint (graph B). Association statistics in the graphs are computed from the displayed data. see Figure 2.1 in Brokerage and Closure (or Figure 5 in Burt, "Structural holes and good ideas," 2004 American Journal of Sociology) Brokerage, Good Ideas, and Innovation, Digging a Little Deeper J 3.5 0.9 E E J Y = a + b ln(C) E ^ a ^b t Judge 1 6.42 -1.04 -5.8 Judge 2 4.08 -.63 -3.9 Combined 5.51 -.91 -7.4 E E G 2.5 G 0.8 ^ P(no idea) 11.2 logit test statistic 0.7 J J 0.6 J E J E J 0.5 E G J G G E 10 20 30 40 50 G C C G G C G 60 C C J G G 1 J C C 70 80 90 100 10 C 20 30 40 C C ^ P(dismiss) 5.5 logit C test statistic C J G G C C J G G 0.4 J E E 1.5 J C J J G 2 C E E E ". . . for those ideas that were either too local in nature, incomprehensible, vague, or too whiny, I didn't rate them" 50 60 70 80 90 Probability Management Evaluation of Idea's Value Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 25) E 3 J J E 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 100 Network Constraint (C) on Manager Offering Idea from Figure 2.1 in Brokerage and Closure (or Figure 5 in Burt, "Structural holes and good ideas," 2004 American Journal of Sociology) In Sum, Brokers Do Better B. High achievement is associated with large, open networks (R2 = .36, n = 85, t = -6.78) (evaluation, compensation, promotion) Z-Score Residual Achievement A. High achievement is associated with many nonredundant contacts (R2 = .39, n = 125, t = 6.52, -4.12) Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 26) 24+ NonRedundant Contacts few ——— Structural Holes ——— many Network Constraint many ——— Structural Holes ——— few Graphs show achievement — evaluation, compensation, and promotion — increasing with more access to structural holes in six populations (analysts, bankers, and managers in Asia, Europe, and North America; Burt, 2010:26, cf. Burt, 2005:56). Circles in graph A are average scores on the vertical axis within integer numbers of nonredundant contacts. Circles in graph B are average scores on the vertical axis for five-point intervals of network constraint. Bold line is the vertical axis predicted by a function of nonredundant contacts (graph A, linear and squared terms; dashed regression line is through zero to six nonredundant contacts, R2 = .70, n = 39, t = 4.97, -2.70), or the natural logarithm of network constraint (graph B). Association statistics in the graphs are computed from the displayed data. Three Summary Points Network Structure Is a Proxy for the Distribution of Information For reasons of opportunity, shared interests, experience — simple inertia — organizations and markets drift toward the bridge-and-cluster structure known as a “small world.” Over time, information becomes "sticky" within clusters, different between clusters. In Which Network Brokers Have a Competitive Advantage Bridge relations across the structural holes between clusters provide information breadth, timing, and arbitrage advantages, such that network brokers managing the bridges are at higher risk of “productive accident” in detecting and developing good ideas. They are the source of significant innovation in organizations and markets. In return, network brokers tend to be better compensated than peers, more widely celebrated than peers, and promoted more quickly to senior rank relative to peers; in short, brokers do better. Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 27) Three Points Follow from the Link between Network Brokerage & Innovation - Closed networks do not identify unintelligent managers so much as expert specialists. - Innovation is an import/export process. Value is not created at the innovation source. It is created each time productive knowledge produces innovation in a target audience. - Innovation depends on the network as well as the person. Innovation does not depend on individual genius so much as it depends on employees finding opportunities to broker knowledge from where it is routine to where it would create value. Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 28) Appendix Materials Appendix I: Example Network Questionnaire for a Web Survey Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 29) for discussion of these slides and how to collect network data, see Appendix A, "Measuring the Network," in Neighbor Networks. Figure A1 in Neighbor Networks Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 30) Appendix I, continued Figure A2 in Neighbor Networks Appendix II: Network Metrics* from Burt, "Formalizing the argument," (1992, Structural Holes); "Gender of social capital" (1998, Rationality and Society); Appendix B "Measuring Access to Structural Holes," (2010, Neighbor Networks). Network brokerage is typically measured in terms of opportunities to connect people. When everyone you know is connected with one another, you have no opportunities to connect people. When you know a lot of people disconnected from one another, then you have a lot of opportunities to connect people. “Opportunities” should be emphasized in these sentences. None of the usual brokerage measures actually measures brokerage behavior. They index opportunities for brokerage. Reliability and cost underlie the practice of measuring brokerage in terms of opportunities. It is difficult to know whether or not you acted on a brokerage opportunity. One can know with more reliability whether or not you had an opportunity for brokerage. Acts of brokerage could be studied with ethnographic data, but the needed depth of data would be expensive, if not impossible, to obtain by the practical survey methods used to measure networks. Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 31) Good reasons notwithstanding, the practice of measuring brokerage by its opportunities rather than its occurrence means that performance has uneven variance across levels of brokerage opportunities. Performance is typically low in the absence of opportunities. Performance varies widely where there are many opportunities: (1) because some people with opportunities do not act upon them and so show no performance benefit, (2) because it is not always valuable to move information between disconnected people (e.g., explain to your grandmother the latest technology in your line of work), or (3) because the performance benefit of brokerage can occur with just one key bridge relationship. A sociologist might do more creative work because of working through an idea with a colleague from economics, but that does not mean that she would be three times more creative if she also worked through the idea with a colleague from psychology, another from anthropology, and another from history. The above three points can be true of brokerage measured in terms of action, but under the assumption that people invest less in brokerage that adds no value, the three points are more obviously true of brokerage measured in terms of opportunities. It could be argued that people more often involved in bridge relations are more likely to have one bridge that is valuable for brokerage, and to understand how to use bridges to add value, but the point remains that the network measures discussed below index opportunities for brokerage, not acts of brokerage. Bridge Counts Bridge counts are an intuitively appealing measure. The relation between two people is a bridge if there are no indirect connections between the two people through mutual contacts. Associations with performance have been reported measuring brokerage with a count of bridges (e.g., Burt, Hogarth, and Michaud, 2000:Appendix; Burt, 2002). Constraint I measure brokerage opportunities with a summary index, network constraint. As illustrated on the next page, network constraint begins with the extent to which manager i’s network is directly or indirectly invested in the manager’s relationship with contact j (Burt 1992: Chap. 2): cij = (pij + Σqpiqpqj)2, for q ≠ i,j, where pij is the proportion of i’s network time and energy invested in contact See Appendix III to get free software to do these calculations for you. We use the software in the follow-on course, 39006. Illustrative Network and Computation A B F Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 32) Constraint measures the extent to which a network doesn't span structural holes C E D Network constraint measures the extent to which your network time and energy is concentrated in a single group. There are two components: (direct) a contact consumes a large proportion of your network time and energy, and (indirect) a contact controls other people who consume a large proportion of your network time and energy. The proportion of i’s network time and energy allocated to j, pij, is the ratio of zij to the sum of i’s relations, where zij is the strength of connection between i and j, here simplified to zero versus one. cij = (pij + Σq piqpqj)2 q ≠ i,j network data contact-specific constraint (x100): A B C D E F 15.1 8.5 2.8 4.9 4.3 4.3 100(1/36) A B C D E F gray dot total 39.9 = aggregate constraint (C = Σj cij) . 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 . 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 . 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 . 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 . 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 . 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 . j, pij = zij / Σqziq, and variable zij measures the strength of connection between contacts i and j. Connection zij measures the lack of a structural hole so it is made symmetric before computing pij in that a hole between i and j is unlikely to the extent that either i or j feels that they spend a lot of time in the relationship (strength of connection “between” i and j versus strength of connection “from” i to j; see Burt, 1992:51). The total in parentheses is the proportion of i’s relations that are directly or indirectly invested in connection with contact j. The sum of squared proportions, Σjcij, is the network constraint index C. I multiply scores by 100 to discuss integer levels of constraint. The network constraint index varies with three network dimensions: size, density, and hierarchy. Constraint on a person is high if the person has few contacts (small network) and those contacts are strongly connected to one another, either directly (as in a dense network), or through a central, mutual contact (as in a hierarchical network). The index, C, can be written as the sum of three variables: Σj(pij)2 +2Σjpij(Σqpiqpqj) + Σj(Σqpiqpqj)2. The first term in the expression, C-size in Burt (1998), is a Herfindahl index measuring the extent to which manager i’s relations are concentrated in a single contact. The second term, C-density in Burt (1998), is an interaction between strong ties and density in the sense that it increases with the extent to which manager i’s strongest relations are with contacts strongly tied to the other contacts. The third term, C-hierarchy in Burt (1998), measures the extent to which manager i’s contacts concentrate their relations in one central contact. See Burt (1992:50ff.; 1998:Appendix) and Borgatti, Jones, and Everett (1998) for discussion of components in network constraint. Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 33) Size Network size, N, is the number of contacts in a person's network. In graph-theory discussions, the size of the network around a person is discussed as “degree.” For non-zero network size, other things equal, more contacts mean that a manager is more likely to receive diverse bits of information from contacts and is more able to play their individual demands against one another. Network constraint is lower in larger networks because the proportion of a manager’s network time and energy allocated to any one contact (pij in the constraint equation) decreases on average as the number of contacts increases. Density Density is the average strength of connection between contacts: Σ zij / N*(N-1), where summation is across all contacts i and j. Dense networks are more constraining since contacts are more connected (Σqpiqpqj in the constraint equation). Contact connections increase the probability that the contacts know the same information and eliminate opportunities to broker information between contacts. Thus, dense networks offer less of the information and control advantage associated with spanning structural holes. Density is only one form of network closure, but it is a form often discussed as closure. Hypothetical networks in the figure on page 35 illustrate how constraint varies with size, density, and hierarchy. Relations are simplified to binary and symmetric in the networks. The graphs display relations between contacts. Relations with the person at the center of the network are not presented (that person at the center is referenced by various labels such as "you," "ego," or "respondent"). The first column in the figure contains examples of sparse networks (zero density). No contact is connected with other contacts. The third column of the figure contains maximum-density networks (density = 100). Every contact has a strong connection with each other contact. At each network size, constraint is lower in the sparse-network column. Hierarchy Density is a form of closure in which contacts are equally connected. Hierarchy is another form of closure in which a minority of contacts, typically one or two, stand above the others for being more the source of closure. The extreme is to have a network organized around one contact. For people in job transition, such as M.B.A. students, that one contact is often the spouse. In organizations, hierarchical networks are sometimes built around the boss. Hierarchy and density both increase constraint, but in different ways. They enlarge the indirect connection component in network constraint (Σqpiqpqj). Where network constraint measures the extent to which contacts are redundant, network hierarchy measures the extent to which the redundancy can be traced to a single contact in the network. The central contact in a hierarchical network gets the same information available to the manager and cannot be avoided in manager negotiations with each other contact. More, the central contact can be played against the manager by third parties because information available from the manager is equally available from the central contact since manager and central contact reach the same people. Network constraint increases with both density and hierarchy, but density and hierarchy are empirically distinct measures and fundamentally distinct with respect to social capital because it is hierarchy that measures social capital borrowed from a sponsor. Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 34) To measure the extent to which the constraint on a person is concentrated in certain contacts, I use the Coleman-Theil inequality index for its attractive qualities as a robust measure of hierarchy (Burt, 1992:70ff.). Applied to contact-specific constraint scores, the index is the ratio of Σj rj ln(rj) divided by N ln(N), where N is number of contacts, rj is the ratio of contact-j constraint over average constraint, cij/(C/N). The ratio equals zero if all contact-specific constraints equal the average, and approaches 1.0 to the extent that all constraint is from one contact. Again, I multiply scores by 100 and report integer values. In the first and third columns on the next page, no one contact is more connected than others, so all of the hierarchy scores are zero. Non-zero hierarchy scores occur in the middle column, where one central contact is connected to all others who are otherwise disconnected from one another. Contact A poses more severe constraint than the others because network ties are concentrated in A. The Coleman-Theil index increases with the number of people connected to the central contact. Hierarchy is 7 for the three-contact hierarchical network, 25 for the five-contact network, and 50 for the ten-contact network. This feature of hierarchy increasing with the number of people in the hierarchy turns out to be important for measuring the social capital of outsiders because it measures the volume of social capital borrowed from a sponsor, which strengthens the association with performance (this point is the focus of the later session on outsiders having to borrow network access from a strategic partner). Note that constraint increases with hierarchy and density such that evidence of density correlated with performance can be evidence of a hierarchy effect. Constraint is high in the dense and hierarchical three-contact networks (93 and 84 points respectively). Constraint is 65 in the dense five-contact network, and 59 in the hierarchical network; even though density is only 40 in the hierarchical network. In the ten-contact networks, constraint is lower in the dense network than the hierarchical network (36 versus 41), and density is only 20 in the hierarchical network. Density and hierarchy are correlated, but distinct, components in network constraint. Partner Networks Clique Networks A A A C B Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 35) contacts density x 100 hierarchy x 100 constraint x 100 from: A B C D E nonredundant contacts betweenness (holes) C B 3 0 0 33 3 67 7 84 3 100 0 93 11 11 11 3.0 3.0 44 20 20 1.7 0.5 31 31 31 1.0 0.0 A A A E Larger Networks D B B D C E B D C ok B C 5 0 0 20 5 40 25 59 5 100 0 65 4 4 4 4 4 5.0 10.0 36 6 6 6 6 3.4 3.0 13 13 13 13 13 1.0 0.0 10 0 0 10 10.0 45.0 10 20 50 41 8.2 18.0 10 100 0 36 1.0 0.0 Still Larger Networks contacts density x 100 hierarchy x 100 constraint x 100 nonredundant contacts betweenness (holes) e rs Network Density E D Cliques Br contacts density x 100 hierarchy x 100 constraint x 100 from: A B C nonredundant contacts betweenness (holes) C Partners Network Hierarchy Small Networks Broker Networks To keep the diagrams simple, relations with ego are not presented. Network Constraint decreases with number of contacts (size), increases with strength of connections between contacts (density), and increases with sharing the network (hierarchy). This is Figure 1 in Burt, "Reinforced Structural Holes," (2015, Social Networks, an elaboration of Figure B.2 in Neighbor Networks). Graph above plots density and hierarchy for 1,989 networks observed in six management populations (aggregated in Figure 2.4 in Neighbor Networks to illustrate returns to brokerage). Dot-circles are executives (MD or more in finance, VP or more otherwise). Hollow circles are lower ranks. Executives have significantly larger, less dense, and less hierarchical networks. Network Constraint (x 100) Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 36) many ——— Structural Holes ——— few Network Constraint (x 100) many ——— Structural Holes ——— few Ego-Network Betweenness -.71 correlation with log constraint (Number Monopoly-Access Holes) Ego-Network Betweenness (Number Monopoly-Access Holes) NonRedundant Contacts -.90 correlation with log constraint R2 = .99 R2 = .92 NonRedundant Contacts few ——— Structural Holes ——— many The Network Measures of Access to Structural Holes Are Strongly Correlated These are network metrics for 801 senior people in two organizations analyzed in Burt, "Reinforced structural holes" (2015, Social Networks). One organization is a center-periphery network of investment bankers (circles). The other is a balkanized network of supply-chain managers in a large electronics company (squares). The point is that networks rich in structural holes by one measure tend to be rich in the other measures. Structural Folds Indicate Access to Structural Holes 11 7 3 14 1 4 2 6 5 Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 37) Kind of Network 8 12 9 10 15 13 Network Effective Size Network Size (NonRedundant Constraint (Contacts) Contacts) Ego-Network Betweenness (Structural Holes) 16 Reinforced Holes (RSH) Raw Normalized Ego-Network Modularity (Newman Q) Closed (3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16) 3 1.0 92.6 .00 .00 0% .00 Broker (1) 2 2.0 50.0 1.00 .75 75% .00 Broker (2, 6) 4 2.5 58.3 3.00 1.75 29% .00 Fold Broker (10) 6 4.0 46.3 9.00 6.00 40% .50 This is Figure 3 in Burt, "Reinforced structural holes" (2015, Social Networks), based on the above networks in Figure 1 of Vedres and Stark, "Structural folds: generative disruption in overlapping groups" (2010, American Journal of Sociology). Correlations to the right are across the 801 bankers and managers analyzed in the 2015 article. Log Constraint 1.00 Effective Size -.90 1.00 EN Betweenness -.71 .88 1.00 RSH -.71 .93 .91 Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 38) *node data id ego A B C D E F *tie data from to tie ego A 1 ego B 1 ego C 1 ego D 1 ego E 1 ego F 1 A B 1 E A 1 F A 1 B D 1 Appendix III: NetDraw Quick Start Making your own sociograms and computing network metrics for a group, project, organization, or market 1. DOWNLOAD THE FREE NETWORK SOFTWARE, NETDRAW (https://sites.google.com/site/netdrawsoftware/ download, then click on the "Exe only" option) 2. TYPE THE 21 LINES TO THE RIGHT INTO YOUR WORD PROCESSOR AND SAVE AS A TEXT FILE ENDING IN .vna The 21 lines are a roster of people in the network followed by a roster of relations (e.g., ego has a relation to person A at strength 1). These data define the network illustrating network constraint on page 32 in this handout. 3. LOAD THE .vna FILE INTO NETDRAW (“File” menu, “open” option, then “VNA text file” and “Complete”) 4. GENERATE A SPATIAL DISPLAY OF THE NETWORK (“Layout” menu, “graph theoretic layout” option, then “spring embedding”). YOU SHOULD GET THE SOCIOGRAM BELOW. (See next page for basic nets discussed in this course.) Now play around to learn the wide capabilities of the software. Click and drag a node to move it and its relations around. Remove arrows by clicking on the arrow button to the right of the row of command buttons just above the sociogram display. Save the sociogram to a file for editing, pasting, and printing (“File” menu, “save diagram as” option, then “metafile”). D For more complex edits, such as computing network metrics (“Analysis” menu, “structural holes” option, then “ego network model” and save the data), see the short user guide you can download on the page where you clicked "Exe only." If you are not comfortable using new software, it might be wise to bring in someone who can play with the software then brief you. FOR TEXT EXPLAINING THE NETWORK METRICS, see Appendix II in this handout. Caution: Some versions of NetDraw compute incorrect values of network constraint for isolates. Network constraint is infinite for isolates, so constraint should be its maximum of one. Some versions of NetDraw report a value of zero for infinity. This issue is not likely an issue for you since you probably have contacts, else you wouldn't be using the software. E ego F C B A Appendix IV: Network Endogeneity Most Distributed Independent Network Effect Most Centralized Leadership Leadership (slow, happy) (fast, unhappy) A C C B D B B E B C D C D A A E Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 39) CIRCLE (50.4 sec) N NC Happy A 2 50 58.0 B 2 50 C 2 D E CHAIN (53.2 sec) N NC Happy A 1 100 45.0 64.0 B 2 50 50 70.0 C 2 2 50 65.0 D E 2 50 71.0 Avg 2.0 50.0 65.6 A E D Y-NETWORK (35.0 sec) N NC Happy A 1 100 46.0 82.5 B 1 100 50 78.0 C 3 2 50 70.0 D E 1 100 24.0 Avg 1.6 70.0 59.9 WHEEL (32.0 sec) N NC Happy A 1 100 37.5 49.0 B 1 100 20.0 33 95.0 C 4 25 97.0 2 50 71.0 D 1 100 25.0 E 1 100 31.0 E 1 100 42.5 Avg 1.6 76.7 58.4 Avg 1.6 85.0 44.4 The four networks are from the Bavelas-Leavitt experiments on leadership in task groups. The WHEEL is a traditional bureaucracy in which C is in charge. The other three networks involve distributed leadership (all five people in the CIRCLE; B, C, and D in the CHAIN; C and D in the Y-NETWORK). More distributed leadership is associated with more messages, slower task completion, and greater enjoyment. Speed, messages, and enjoyment scores are from Leavitt (1951). Number of contacts (N) and network constraint (NC) are computed from binary ties in the sociograms (number of contacts equals number of non-redundant contacts in these structures). Figure 2.4 in Burt (2017, Structural Holes in Virtual Worlds) Information messages Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 40) Network Constraint Mean Enjoyment Score Mean Messages Sent Answer messages Enjoyment after first trial Enjoyment after last trial Network Constraint Times Cited as Group Leader Behavioral and Opinion Correlates of Network Brokers Network Constraint ( ) A. Network brokers tend to distribute answers, people in moderately constrained positions tend to be conduits for informational messages. B. Network brokers are least happy initially, but eventually become the most pleased with the experience. C. The final outcome, by the end of the experiment, is that network brokers are most likely to be recognized as the unofficial group leader. Data are from Leavitt (1949: Table 30, following page 62). Data are from Leavitt (1949:Table 29, pages 60-61; "How did you like your job in the group?). Data are from Leavitt (1949: Table 8, page 38; “Did your group have a leader? If so, who?”). Figure 2.5 in Burt (2017, Structural Holes in Virtual Worlds) 30 XXX X X X X XX X X X X XXX X X X X Appendix V: Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 41) National Differences in Business Culture Years Acquainted with Contact X 25 20 X XX X X X X X X XXXXX X X X X X X XXXX X XX X XXX X XX X XX X X X X X XX X X XX X X X XX X X XXXXXX XXX XX X X X X X XX X X X X X X X XXX X X XX X X XXX XX X XXXX X X X 15 10 5 X 0 0 5 15 10 X XX X X X XX XX X X X XX X X X X X XX X X X XX X X X X X XX X X X X X XX X XX XXX X XX X X X X XX X XX X XX XX X X X X X X X X X X X X X X XX X X X X X XX X XX XX X XXX X XX XX X XX X X X X X XX X X XX X X X X X X XX X X X X X X X X X X X XX XX X XX XX X X X X X X X X X X X X X XX X X XX XX X X X XX X X X XX 20 25 French Manager Years in the Firm 30 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 X X X XX XX X X XX X X X X X X X X X X X X X XXX X X X X X X X XX XXX XX XX X X X X X XX XX XX XX X X X X XX X X XX X X X X X X XX X X X XXX X XX X X XX X X XX X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X XX X X X X X X XX XX X X X X X X X X X X X X X XX X XXX XX X XX X X X X X XX X X XX X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X XX X X X XX X X X X X X X XX XX X X X X XXXX X X XX X XX X X XX X X X XXXX XX X X X X X XXX X X X X X XX XX X X XX X X X X XX X XXXX XX X X X XX X X X X X X X X X X XX X X X X X X X X X X XX X X X X X X X XX X XX X X X X X X X X XX X X X X XX X X X X X XX X X X X XX X X XXXX X X X X XX X X X X X X XX X X X X X X X X X X X X X X XX X X X XX X X X X X X X X X X X X X X XX X X X XX X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X XX X XX X X X X X X XX X X XX X X XX X X X X X X X X X XX X X X XX X XX XXXX XX X XXX X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X XX X X X XX XX X X X X X X X X XX X X XX X XXX X X XX X X X X X X XX X XXX X X X X X XX X X X X X XX X X X XX XX X XX X X X X X XX X X X XX X X X XX X X XXX X X X XX X X X X X X X XXX X X X X XXX XX X XXX X X X X XXX XX XXX X XX X X X XX X X X XX XX X X XX XX X X X X X X XX X X X X X X X X XX X X XX X XX X X X X XX X X X X X X XXX XX X X XX X X XXX X X X X XX X X X X X XX X X XX X X X XX XX XX XX X X X X XXXX X X X XXXX X XXX X X X XX X X X X X X 0 5 15 10 20 25 American Manager Years in the Firm Colleague Relations Predating Entry into the Firm French Managers American Managers Years in the Firm Number Colleagues % Known Before Firm Mean Years Known Number Colleagues % Known Before Firm Mean Years Known 0 to 10 105 26% 5.2 691 81% 12.6 11 to 20 160 15% 8.2 875 42% 13.5 Over 20 391 5% 10.3 129 6% 14.9 Total 656 11% 9.0 1695 55% 13.0 from Burt, Hogarth, and Michaud "The social capital of French and American managers" (2000, Organization Science) 30 Distinctions Between Kinds of Relations (relations close together reach the same contacts) supervisor J less J close knew before J valued J less than monthly close weekly J monthly less than monthly J J J difficult J discuss exit J Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 42) 3-9 American Managers other J J subordinate discuss personal J daily J J J esp close valued J J close 10+ J esp close difficult French Managers supervisor J buy-in J J monthly J distant JJ socialize 1-2 less close J 3-9 J J J distant J J other subordinate J 10+ J buy-in J J J 1-2 J knew before weekly J daily J discuss personal J J discuss exit J socialize from Figure 1.7 in Brokerage and Closure (cf. Figure A3 in Neighbor Networks) Number of Groups Average Character Level 60 50 All Characters 40 30 20 10 A 00 0 a b 3 7 11 15 19 Probability of Founding a Group 3.0 23 25+ Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 43) This is Figure 3.6 in Burt, Structural Holes in Virtual Worlds (2017). Achievement increases with access to structural holes between nonredundant contacts. Graph A describes EverQuest II (EQ2). Graphs B and C describe achievement in Second Life. a Zero refers to isolates, people with no network as defined in text and no group/guild affiliations. b Zero refers to people with no network, but affiliated with groups in Second Life or guilds in EQ2. Number of Groups Founded 2.5 0.5 2.0 0.4 1.5 0.3 Founded Groups Still Active 1.0 0.5 0.0 0.2 B 00 0 a 3 b Effective Size (Number NonRedundant Contacts) Detail on Achievement and Network in Second Life 0.6 7 11 15 19 0.1 0 23 25+ Number NonRedundant Friends 00a 0b C 3 7 11 15 19 23 25+ 90 80 Total Members across All Groups Founded 70 60 50 40 Members in Largest Group Founded 30 20 10 0 Members in Groups Founded Player’s Primary Character 0.7 Probability of Founding 3.5 70 Strategic Leadership Network Brokerage (page 44) (for 77 electronic firms with R&D departments) Predicted Probability of Company Patents Returns to Brokerage for Entrepreneurs in the Renewal of the Chinese Economy Sample of 700 Chinese CEO entrepreneurs in 2012. Networks are key contacts during important events in company history, most valuable current contacts, most valuable senior employee, and most difficult contact. 1% r = .84 Network Constraint many ——— Structural Holes ——— few 50% mean network size network density non-redundant contacts network constraint (x100) 4 11.0 1.0 27.2 mean percent family frequency (days) years known contacts 0.0 1.0 3.1 0.0 11.6 9.7 mean number of employees year company founded 14 1985 67 2001 99% 6 10 46.7 100.0 3.5 7.6 51.2 81.8 426 60.0 CEO's 50.2 cite no 26.1 nuclear or extended 1105 family! 2010 (61%) NOTE — The above graph contains the 77 electronics companies with R&D departments. The Y axis is from a logit equation predicting whether or not each of the 700 companies had filed for patents (73% had not filed for patents). The predictors include years since founding (0.79 z-score), number of company employees (2.35 z-score), whether the company had an R&D department (9.19 z-score), log network constraint (-2.97 z-score, P < .01), an adjustment for lower patenting in textiles, transportation equipment, and medicine manufacturing (-2.17 z-score), and an adjustment for a weaker network effect in the lower patenting industries (2.16 z-score). For contextual background on the sample CEOs, see Nee and Opper, Capitalism from Below: Markets and Institutional Change in China (2012, Harvard University Press). Also see Merluzzi (2013, "Social Capital in Asia," Social Science Research).