Document 14534998

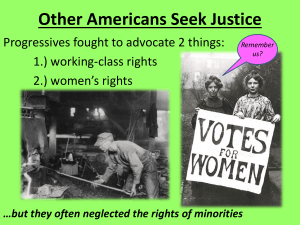

advertisement