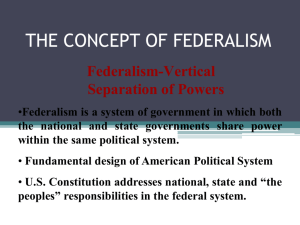

Nationwide thinking, nationwide planning, nationwide

advertisement