The October Crisis

advertisement

The October Crisis

There had been little political violence in Canada in the twentieth century. Moreover, Canada was also at peace

externally, a happy contrast to its belligerent southern neighbour, then bogged down in the Vietnam War. With a

philosopher-prime minister known to disapprove of the military (which had just been drastically reduced in size),

this state of affairs seemed likely to continue.

The military, certainly, was discontented, but its opinions counted for little. It found new roles to play: in the

autumn of 1969, when the police of Montreal went out on strike, the army was called in by the civil authorities to

restore order after a night of rioting. In the fall of 1969, however, the Montreal authorities had something else on

their minds: terrorism. The cause of an independent Quebec had not yet flourished at the polls, and some of its

sympathizers, especially those on the extreme left, thought it was time to hurry things along with a few well placed

bombs. In their view the illegitimate capitalist state was by its very existence in an attitude of war with its subjects.

Capitalism could be purged only by violence, and, in Montreal, with its highly visible and generally prosperous

English-speaking minority, anti-capitalism could easily blend with anti-colonialism. National liberation struggles

overseas, especially in Algeria, Bolivia, and Cuba, furnished ready-made models of heroic struggle, and the rest

was easy: thefts from armories, construction sites, or gun stores provided the arsenal of the revolution.

Omelettes are not made without breaking eggs, according to the jargon of the period, and revolutions are not won

without at least some incidental deaths: such violence could be justified afterward in press releases, or more often

shrugged off. The press was eager to publicize it, and horror was always good copy, so that the terrorists of the

Front de liberation de Quebec (or FLQ) could always be assured of an instant audience. The Front was a selfperpetuating entity. Current evidence suggests that it never had much of a formal organization; rather, small

groups of individuals appropriated the title from time to time, thereby preserving the illusion of a continuing, hydraheaded conspiracy.

It was such a conspiracy that the municipal authorities of Montreal depicted in testimony in Ottawa. But their

testimony had little effect. Ordinary police procedures turned up terrorists from time to time, and these men were

periodically brought before the courts and sent off to the penitentiary. Their crimes, though serious, did not

demand more than the ordinary powers of justice for their suppression. It was true that terrorism was growing

more frequent: in November and December 1969 there were five separate bombing incidents in Montreal. In June

1970, a plot to kidnap the Israeli consul in Montreal was uncovered. The well-publicized arrests of two

revolutionary theorists, Pierre Vallieres and Charles Gagnon, contributed to the general excitement. And in

August 1970 there was a new twist: FLQ terrorists, training with the Palestinian terrorists, announced that they

would soon renew their struggle, using selective assassination as a weapon.

When, on October 5, 1970, the British trade commissioner in Montreal, James Cross, was abducted from his

home, terrorism was very much in the air. Before long a press release arrived from the FLQ announcing its terms

for the release, unharmed, of Cross. They included a ransom ('voluntary tax') of $500,000 in gold ingots, the

release of a list of 'political prisoners' then serving time for their crimes, re-employment of some former post office

drivers in Montreal, no police pursuit, free transport out of the country, and the reading of the FLQ manifesto and

all subsequent communiqués on radio and television.

The manifesto, a hysterical and abusive potpourri of grievances combined with a distorted view of history,

attempted to justify FLQ actions in terms of the rhetoric of colonial revolution and national struggle. In tone and

substance it was not greatly different from thousands of bygone leaflets that had passed unhindered from the

printing press into the wastebasket. But this time it was different: the FLQ had a hostage, and the price for his life

was national attention.

The ultimate responsibility for a diplomat's safety rests squarely in the hands of the federal government. But police

power is, for the most part, a local matter, and in this case responsibility lay with the city of Montreal and the

Quebec provincial police. There were anxious consultations among the various levels of government as to the

proper policy to be adopted, but it is impossible, even now, to say just what proposals were made during these

discussions. What is certain is the result: a decision to bargain with the FLQ by agreeing to comply with some of

its less dangerous demands. As the terrorists had demanded, the FLQ manifesto was published and broadcast,

safe passage was guaranteed for the kidnappers, and the Attorney General of Quebec promised that he would

support parole for some of the 'political prisoners.'

The partial surrender by the constituted authorities in Ottawa and in Quebec was well intentioned: if Cross's life

could be saved, then some concessions, even in the face of terror, were worthwhile. But concessions enforced at

the barrel of a gun may tend to give the impression that more can be extracted if the price is raised; and so, while

the first kidnapping cell of the FLQ continued to hold on to Cross, another self-constituted group, describing itself

as the 'Chenier financial cell,' swept up Quebec's Minister of Labour, Pierre Laporte, as he played ball with his

children outside his suburban house on October 10.

Although the Cross kidnapping was taken seriously, the authorities remained calm; but the abduction of Laporte

threw many in the Quebec government into a state of panic. Ministers flew their families out of the province: the

less timid to Ottawa; others as far as New York. Pierre Laporte was the second minister in the Quebec

government; he had been a strong contender for the Liberal leadership only nine months before. Laporte's

disappearance affected the innermost circles of Quebec politics.

Events moved quickly to a crisis. As the police, quarrelling among themselves, pursued the search for Cross and

Laporte, the provincial government dithered over what to do. It was speculated that a coalition government might

be formed comprising all the parties in a kind of national union in order to find a way out of the crisis. Bourassa

himself did not engender sufficient confidence, and it was darkly suspected that he would cave in to hardline

pressure from Trudeau. A hard line, in the eyes of many influential Quebecois, would mean refusal to comply with

some, at least, of the terrorists' demands, such as the release of 'political prisoners.' The lives of two men were

concrete: the legitimacy and authority of the state were abstract. Many intellectuals and journalists and some

politicians plumped for the concrete, but the situation is by no means as clear-cut as these individuals then seem

to have believed it to be. Terrorism poses both a theoretical and a practical problem to those who confront it

(naturally it poses no problem at all to those who sympathize with or support it). As one recent student of the

phenomenon of terrorism has argued, 'It is an important, sometimes over-riding, terrorist aim to undermine the

political will, confidence and morale of liberal governments and citizens so that they are made more vulnerable to

political and social collapse.'2 More practically, one terrorist act, if one is to judge by experience abroad, will most

likely lead to another. Events in Brazil in the same year, 1970, furnish an illustration: in September 1969 terrorists

seized the American ambassador. The price for his release was fifteen prisoners. The West German

ambassador's turn came in June 1970: his ransom was forty prisoners. The Swiss ambassador followed in

December 1970: his release was extorted at the cost of seventy prisoners. And, once undertaken, the tactic of

conceding terrorist demands takes on a crazed logic of its own: what was given for one must be given for the

next.

As we know, some of these considerations were in the minds of Canada's federal and provincial governments as

they contemplated the difficult question of what to do. Evidence of confusion and demoralization was painfully

apparent in the days after the Laporte kidnapping, when it was argued that only a new government (even though

the democratically elected government of Quebec was only six months old) could have the authority and

legitimacy to deal with the real crisis.

What could that crisis be? In the eyes of many observers, it was the rigid and inflexible attitude that Ottawa was

said to be taking in refusing to contemplate any further concession to the terrorists' demands: for any further

concession, as Trudeau and his ministers knew, meant the release, before their sentences were served, of many

or all of the 'political prisoners' then held in federal penitentiaries. Bourassa was said to be inclined to a softer line

(although some evidence that has appeared since contradicts this). In order to 'strengthen' Bourassa's hand,

therefore, sixteen prominent Quebec personalities, including various labour and business leaders, Claude Ryan,

and Rene Levesque, urged the Premier to persevere despite and against all obstruction from outside Quebec' in

order to negotiate the 'exchange of the two hostages for the political prisoners.' The use of the term political

prisoners without quotation marks surprised some, even when Ryan justified it as a 'question of fact and not law,'

in itself a curious phrase. The implication that it was up to Quebec to solve its own problems, and that interference

from 'outside' (meaning the rest of Canada) was illegitimate, was familiar enough in the separatist camp, but

alarming when it came from those not already committed to Quebec's independence.

That same day, October 14, less respectable elements in Quebec society were taking action designed to support

the FLQ. The lawyer negotiating on behalf of the terrorists urged a meeting of Universite de Montreal students to

boycott classes; the boycott began the next day. At another Montreal college, students occupied their rector's

office, proclaiming that they would stay there 'until the victory of the FLQ.' That evening, a rally was held in

Montreal's Paul Sauve arena, with an audience of three thousand chanting 'FLQ ... FLQ ... FLQ.' Michel

Chartrand, a Montreal labour leader, told the audience that the FLQ was going from strength to strength. 'There is

no doubt,' he said, 'that there are infinitely more people now in accord with them, who understand and sympathize

with the objectives of the FLQ than there were in 1963 and 1966.' Chartrand was doubtless right. Some of those

who, in 1963, condemned the first bombings now remained uneasily silent, either convinced that it was not their

fight, or frightened to speak out. One Montrealer who did speak out while in Toronto was reproached by his fearful

family when he came home: it was dangerous, they explained, to draw attention to oneself.

By Thursday, October 15, a climax was approaching. That evening, a curious conversation took place between

the premier of Quebec and a PQ member of the assembly. 'What do you want me to do?' Bourassa asked. 'You

must immediately form a coalition government,' the Pequiste replied. He urged Bourassa to get rid of the more

hesitant members of his cabinet and replace them with members of the opposition and other public bodies,

including the trade unions. 'That coalition government will oppose Ottawa and negotiate with the FLQ. We haven't

a minute to lose. It's your last chance.' Bourassa, however, refused. It was, he said, already too late.

As the two men spoke, the Canadian army was taking up positions around Montreal, Quebec City, and Ottawa. At

the invitation of the government of Quebec, the troops had come to reinforce the hard-pressed police. It was the

first intimation that the general public had had of the gravity of the crisis, and of the two governments'

determination to resist further concessions to terrorist pressures. More was to come. At three o'clock on the

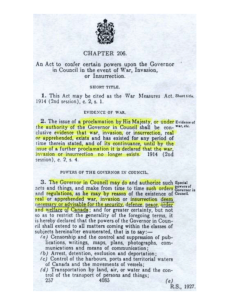

morning of Friday, October 16, the federal government invoked the War Measures Act, declaring that an

apprehended insurrection' existed in Quebec and giving the police extraordinary powers of arrest and detention

against anyone suspected of belonging to, or sympathizing with, the FLQ.

That morning the police began a series of raids across Quebec, rounding up anyone suspected of belonging to

the FLQ. We know now that police intelligence was seriously flawed, and that Ministers found police work most

unsatisfactory. But it was all they had. The size of the round-up seems to have surprised its authors, the federal

cabinet, who had seen a list of only some seventy suspects. In sum, some 436 persons were arrested and

detained under the authority of the War Measures Act during the whole time of the crisis. The selection of whom

to arrest was left in the hands of the police, and the police did not always proceed with due regard for reasonable

evidence. In one notorious case, they entered the home of the federal Secretary of State, Gerard Pelletier, in

search of a different Gerard Pelletier. Their source of information in this case seems to have been the telephone

book.

The immediate effect of the imposition of the War Measures Act was the silencing of the vocal support for the

FLQ which had been so much in evidence in the previous weeks. Of those arrested, sixty-two were eventually

brought to trial, and twenty were convicted. The War Measures Act could not rescue Laporte or Cross, although it

did allow the police to divert more resources to the pursuit of their kidnappers. The FLQ group holding Laporte

murdered its helpless victim on Saturday, October 17 ('executed' is the revolutionary cant it employed) and left his

body in the trunk of a car to be picked up.

Cross was eventually found and released, early in December. His captors traded the British diplomat's life for their

own safe passage out of the country, to Cuba, where they lived, more or less discontentedly, for several years.

They later moved to France, which admitted them as 'political refugees.' Eventually some returned to Canada,

where they were tried, convicted, and, in view of their stated repentance for past misdeeds, given light sentences.

The murderers of Laporte were uncovered in the corner of a country basement later the same month. They too

were tried and convicted; because of the gravity of their offence, they received heavier sentences.

Most of the terrorists' demands were not achieved. No 'political prisoners' won their freedom. Despite the raucous

rhetoric that surrounded the first stages of the kidnapping crisis, the seizure of the two victims did not touch off

revolutionary festivities in the streets of Montreal. Nor was the October Crisis the first of many, as those who

believed in the existence of revolutionary conditions in 'oppressed Quebec' had predicted. Instead, there was a

decline and then a cessation of terrorist activity. That may have been coincidence, or it may have derived from the

vigorous employment of the power of the state to confront and crush terrorism. Once the stakes were raised in the

game of revolutionary theatre, once the governments made plain that those who played at parlour revolution

faced real and immediate sanctions, the enthusiasm for a day of the barricades, FLQ style, noticeably diminished.

The bases of the government's reasoning were explained in a speech by Prime Minister Trudeau on the night of

Friday, October 16. 'Should governments give in to this crude blackmail,' Trudeau informed his television

audience, 'we would be facing the breakdown of the legal system, and its replacement by the law of the jungle ...

Freedom and personal security are safeguarded by laws; those laws must be respected in order to be effective.'

But under the threat of terrorism, extraordinary dangers required extraordinary measures: 'The criminal law as it

stands is simply not adequate to deal with systematic terrorism' - a discovery that other countries besides Canada

have made. Finally, Trudeau emphasized, 'This government is not acting out of fear. It is acting to prevent fear

from spreading ... It is acting to make clear to kidnappers and revolutionaries and assassins that in this country

laws are made and changed by the elected representatives of all Canadians - not by a handful of self-selected

dictators.'

Trudeau's actions provoked much discussion at the time, and much condemnation since. Some alleged that the

government had acted on the basis of inadequate information; it had panicked and used a sledgehammer to

squash a gnat. Others suggested that the government knew well what it was doing: and that was to crush

separatism, legal and democratic, under the guise of suppressing an illegal revolutionary conspiracy. Still others

decried the use of troops to protect public figures and public buildings during the crisis and complained loudly

when Trudeau replied that he would do anything that was necessary to protect constituted authority in Canada.

Trudeau was short with the last variety of questioner. 'Yes,' he said, 'well there are a lot of bleeding hearts around

who just don't like to see people with helmets and guns. All I can say is, go on and bleed, but it is more important

to keep law and order in the society than to be worried about weak-kneed people.'

The first two objections merit serious consideration. In answer to the first complaint, that the government acted

hastily and panicked, it is possible to observe that governments are neither omniscient nor omnipotent. The

concrete information that the government had to hand indicated that the arms and dynamite thefts of the previous

couple of years were largely unaccounted for and that the wild threats of the revolutionaries themselves now had

to be taken more seriously than before. The politicians concluded that the will to resist revolutionary violence in

Quebec was demonstrably weakening. There was a reasonable basis for all this conclusion, and it is not

surprising that the federal government acted as it did to shore up and restore the political will to resist violence in

Quebec.

As for the objection that Trudeau was acting to squash separatism and its most prominent proponents, the Parti

Quebecois, we have the statements of both the Prime Minister and one of his supporters, Bryce Mackasey, during

the crisis. On October 17, Mackasey stressed to the House of Commons that the Parti Quebecois was 'a

legitimate, political party. It wants to bring an end to this country through democratic means, but that is the

privilege of that party.' Trudeau himself made the same point in November to an interviewer. Those who claim that

Trudeau was acting to discredit the PQ must fly in the face of explicit public statements by Trudeau and his

ministers.

The War Measures Act crisis produced one of the highest favourable ratings in public opinion that any Canadian

government has ever achieved. Eighty-seven per cent of Canadians, with no significant variation between English

and French, signified their approval of the government's course. Even so, the government's reputation has

suffered because of its actions. The benefits have been hard to seize upon, the defects and injustices (and there

were many in the way the police applied their powers) easy to criticize. In retrospect it is difficult to understand

what else, legally and politically, could have been done. The government was bound to uphold the law and its

application. It would have been ultimately foolish to concede much of the terrorist program, and it may have been

unwise to concede any. Politically, it is the government's duty to try to manage conditions, including public

opinion, so that danger to the fabric of the Canadian state is avoided or repaired. That it also seems to have done,

averting the possibility of a coalition government in Quebec City, and uniting with, rather than opposing, the

government of Quebec to put down manifestations of support for revolution and terror. In this it acted wisely and

properly.

Nevertheless, the crisis caused Trudeau to lose respect for Bourassa. Other factors later exaggerated the

differences between Ottawa and Quebec: Bourassa's inability to impose an agreement on his cabinet and party

over the Victoria Charter; the excursions of some Quebec ministers into federal jurisdiction; and the Bourassa

government's attempts to compromise with the nationalists over language policy. Trudeau responded publicly and

intemperately, which must have further diminished the esteem in which Bourassa was held inside Quebec.

Source:

Robert Bothwell, Ian Drummand and John English, Canada Since 1945, (University of Toronto

Press: Toronto), 1989. pages 367 - 374