Each student will conduct a seminar session. The focus... follow from the lecture or topic area of the week... THE TRUE SEMINAR

advertisement

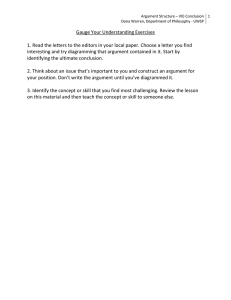

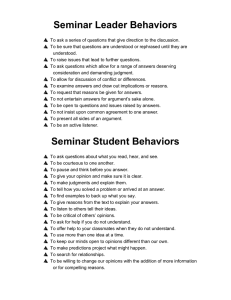

THE TRUE SEMINAR Each student will conduct a seminar session. The focus of the tutorial will follow from the lecture or topic area of the week and is based on an assigned reading. One week before the seminar the leaders must: 1) read the article in order to fully understand it and be able to discuss it in class. Students will then be required to research and investigate the author, along with the ideas associated with it. 2) create a glossary of 5 new and interesting words from the reading. 3) create 5 questions that are central to the understanding of the reading and which will assist them in creating a discussion with their classmates. These questions will be the basis of the seminar discussion and thus will be handed out to their classmates along with the reading. On the day before the seminar the leaders must: 4) hand the question sheet out to classmates along with the reading During the seminar session the leaders must: 5) briefly review the reading with classmates 6) ask questions and provide feedback (stimulate a discussion based on the readings) 7) help guide the discussion to keep the class on topic Written Component Students will write a three page reflection based on the reading. What was the historical context of the time it was written? To what issue does it mainly refer? Why was this issue significant? Assess the arguments made in the reading including their relevance and legitimacy. Remember to focus on the specific time period and to attempt to assess the significance of the paper itself. SEMINAR ASSESSMENT RUBRIC Teacher Name: Mr. Brady Student Name: ________________________________________ CATEGORY Level 4 Enthusiasm (C) Facial expressions and body language generate a strong interest and enthusiasm about the topic in others. Level 2 Facial expressions and body language are used to try to generate enthusiasm, but seem somewhat faked. Content (K) Shows a full Shows a good understanding understanding of the topic. of parts of the topic. Student is able Student is able Student is able Comprehension to accurately to accurately to accurately (TI) answer almost answer most answer a few all questions questions questions posed by posed by posed by classmates classmates classmates about the topic. about the topic. about the topic. Props (A) Student uses several props (could include costume) that show considerable work/creativity and which make the presentation better. Level 3 Facial expressions and body language sometimes generate a strong interest and enthusiasm about the topic in others. Shows a good understanding of the topic. Student uses 1 prop that shows considerable work/creativity and which make the presentation better. Student uses 1 prop which makes the presentation better. Level 1 Very little use of facial expressions or body language. Did not generate much interest in topic being presented. Does not seem to understand the topic very well. Student is unable to accurately answer questions posed by classmates about the topic. The student uses no props OR the props chosen detract from the presentation. Seminar Rubric Level 4 K/U - includes specific REFLECTION and detailed Written information from reflection… the reading (i.e. it integrates direct quotes & paraphrasing) Level 3 - includes specific information from the reading (i.e. direct quotes and paraphrasing used) Level 2 - includes some information about the reading, however it is not used effectively Level 1 - includes limited mention of the reading T/I REFLECTION Written reflection… - includes an assessment of the reading with a high degree of insight - includes an assessment of the reading with a considerable degree of insight - includes an assessment of the reading with some insight - includes an assessment of the reading with limited insight C SEMINAR Seminar presentation… - is clearly linked to readings, presentation is well organized and prepared - the students in the class are involved in the discussion of the readings - is linked to readings, presentation is organized and prepared - efforts are made to draw the class into the discussions of the readings - is mostly linked to readings, presentation is somewhat organized - some effort is made to draw the class into the discussion of the readings - often strays away from readings, presentation has limited organization - there is little effort to include the class in the discussion of the readings A WRITE-UP - Additional Evidence - Questions - Timeline - Provides additional information that brings exceptional understanding to the reading, topic, author, and time period - has a wide variety of questions that range from comprehension to discussion, all questions are clearly expressed - includes challenging and appropriate events in the timeline of historical relevance Provides additional information that brings new understanding to the reading, topic, author, and time period Provides little relevant information to enlighten group and class members Provides no extra information has questions that are very basic, few has questions at the questions are comprehension level clearly expressed with some effort to has a variety of include higher level questions that range questioning, some includes words that from comprehension questions are clearly are very simplistic to discussion, most expressed for the timeline of questions are clearly historical relevance expressed includes words that are mostly appropriate for the includes appropriate timeline of events in the historical relevance timeline of historical relevance SEMINAR TOPIC LIST Approximately 1450-1715 (Renaissance, Reformation, Exploration, Scientific Revolution) Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince, Erasmus Praise of Folly Thomas More Utopia Castiglione The Courtier Martin Luther Various Martin Luther The 95 Theses Martin Luther Sermon in Erfurt Ulrich Zwingli The Sixty-Seven Articles Nicholas Copernicus On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres Galileo Dialogue of the two chief systems of the world Galileo The Starry Messenger Galileo Letter to the Grand Duchess of Tuscany Issac Newton Principia Mathematica Francis Bacon, Interpretation of Kingdom of Man Francis Bacon, Novum Organum Rene Descrates Discourse on Method # & # # # # * * # * * # Approximately 1715-1815 (Absolutism, Enlightenment, French Revolution, Congress of Vienna) Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan John Locke, TwoTreatise of Government * Louis XIV The Code Noir The Duke of Saint Simon The Reign of Louis XIV Frederick William, The Great Elector Monarchical Authority in Prussia James I True Law of Free Monarchies Immanuel Kant What is Enlightenment Thomas Paine The Age of Reason Edmund Burke Reflections on the Revolution in France Thomas Paine The Rights of Man Thomas Paine Common Sense Baron D’Holbach Good Sense Baron D’Holbach The System of Nature David Hume Treatise of Human Nature David Hume The Essay on Miracles Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Inequality among Mankind Jean Jacqus Rousseau: The Social Contract * Jean Jacques Rousseau Emile Mary Woolstonecraft The Rights and Duties of Mankind Blaise Pascal Thoughts Alexander Pope Essay on Man Johnathan Swift A ModestProposal Voltaire Philosophical Dictionary: The English Model Voltaire In Defense of Civilization Voltaire Candide Voltaire The Ignorant Philosopher * # & # # & * * # & # * * * * & Voltaire A Plea for Tolerance and Reason Frederick II Various Works Montesquieu Spirit of the Law Cesare Beccaria Crimes and Punishments Adam Smith The Wealth of Nations Adam Smith The Division of Labour Abbes Sieyes What is the Third Estate Marquis de Condorcet Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind # * # * # * * # 1815-1914 Thomas Malthus Principles of Population Charles Darwin The Origin of Species Bishop Samuel Wilberforce Darwins Faults Thomas Huxley Darwin’s Virtues Herbert Spencer On Social Evolution Herbert Spencer What Knowledge is of most work Giuseppe Mazzini The Duties of Man Giuseppe Mazzini Young Italy Alexis de Tocqueville Democracy in America Henri de Saint Simon The Reorganization of the European community Charles Fourier Design for Utopia F.W. Hegel The State F.W. Hegel Lectures on the Philosophy of History Auguste Comte Cours de philosophie positive John Stuart Mill, On the Subjection of Women (1806-1873) John Stuart Mill, On Liberty Jeremy Bentham Constitutional Code Karl Marx/Friedrich Engels The Condition of the working class in England George Sand Letter to the Rich Friedrich Nietzsche Beyond Good and Evil Friedrich Nietzsche The Birth of Tragedy Friedrich Nietzsche The Genealogy of Morals Jean Paul Sartre Existentialism is a Humanism Leo Tolstoy War and Peace Emile Zola The Experimental Novel Georges Sorel Reflections on Violence Vladimir Lenin What is to be done? * # * * # * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * 1915Mohandas Gandhi Non Violent Resistance John Maynard Keynes The Economic Consequences of Peace Frantz Fanon Black Skin, White Masks Benito Mussolini Article on Facism Jose Ortega Y Gasset The Revolt of the Masses A.J.P. Taylor The Origins of the Second World War Vladimir Lenin State and Revolution Adolf Hitler Mein Kamp & * & & & * * # How to Create good Discussion Questions for your Seminar 1) Good discussion questions are not answered by "yes" or "no." Instead they lead to higher order thinking (analysis, synthesis, comparison, evaluation) about the work and the issues it raises. 2) Good discussion questions call for more than simply recalling facts or guessing what the teacher already wants to know, but are open-ended, leading to a variety of responses. 3) Good questions recognize that readers will have different perspectives and interpretations and such questions attempt to engage readers in dialogue with each other. 4) Good discussion questions depend on a careful reading of the text. They often cite particular scenes or passage and ask people to look at them closely and draw connections between these passages and the rest of the work. 5) Good discussion questions are simply and clearly stated. They do not need to be repeated or reworded to be understood. 6) Good discussion questions are useful to the students. Good questions can help to clarify passages or issues students may find difficult. They help students understand cultural differences that influence their reading. They invite personal responses and connections. 7) Good discussion questions make (and challenge) connections between the text at issue and other works, and the themes and issues of the course. 8) Ask small, detailed questions (like "what's the argument for this conclusion?") before large, abstract questions (like "how does this compare with what so-and-so said?"). 9) Ask interpretative questions (like "what does the author mean here?") before evaluative questions (like "is the author right about this?"). Let your earlier questions lay a foundation for your later questions. 10) Be flexible about your list of questions. If the discussion is going well, go with the flow, but always be ready to bring it back into line when it wanders away from the discipline, or becomes pointless. 11) Be respectful and appreciative at all times, but don't be afraid to disagree with a comment. At the same time, try to avoid getting into a 2-way argument. Be ready to ask, "What do other people think about this?" How to Ensure that your Discussion/Tutorial/Seminar is Effective 1) Don't assume that discussions lead themselves, or that your fascinating subject matter guarantees success. 2) Do not simply ask questions and hope that someone answers them. 3) Plan the discussion. What topics do you want to cover? In what order? What will you do if nobody says anything? 4) Use your own experience in good and bad discussions as a guide. 5) What tends to silence people? What kinds of questions are intimidating, off-putting, unanswerable, patronizing? What kinds invite good discussion? How do you build on previous comments and help the class to do so? 6) You need not have answers to every question you raise, but you should raise good questions, know where in the text to look for answers, and have a plan for leading a discussion that might discover answers. 7) Don't limit the discussion to questions on which you have answers. Use the discussion as an occasion to inquire jointly with other prepared students into questions you find interesting and important. 8) Be creative! Do something different. Make it interesting. Use small groups, use the board, use a computer, use props, and use dramatization. Use your imagination. There's lots of room for creativity in this assignment. (Try to make sure that your innovations enhance, or at least don't detract from, the content.) 9) It's hard to discuss conclusions, but it's easy (and fun and useful) to discuss arguments for conclusions. 10) You don't have to be experts who lecture or who have all the answers. If after a while you feel under pressure to expound or expatiate, then something has gone wrong. Back out of it rather than give in to it. This should be a discussion. 11) Remember all the bad discussions you've had to sit through. Don't repeat their mistakes! 12) In both the presentation and discussion portions of the hour, address the class, not me. 13) The presentation and discussion slots will be filled first-come first-served. Warning! Think ahead and select early, because you will want time to prepare. You may also want to present in one week rather than another based on our reading for that week or your workload for other courses. 14) I will not instantly bail out a bad discussion. There is some instruction in living with the consequences of poor preparation, backing out of a bad question, or dealing spontaneously with a tired or unmotivated class. I will try not to intervene unless I think we have already taken the benefit of that instruction and are wasting time. 15) Make a few notes during the discussion, so that you can competently summarize what has been said at the end of the seminar. Handout Adopted from the OHASSTA website… http://www.ohassta.org/adobefiles/pol_seminaranddiscussions.pdf A Simple System for Critical Analysis of Arguments Because few arguments are presented with perfect clarity, the first step in a logical assessment of an argument must be to prepare the material for proper evaluation. The entire process of analyzing an argument critically--for its inherent rational appeal rather than for its style or for fallacious (deceptive) elements--can be approached in many ways. The following six-step plan offers a useful way of breaking the process into stages: 1. Locate the conclusion: Many arguments are constructed after their conclusions have been determined. Starting with the conclusion may not only reveal special assumptions, but the actual motive behind the argument. An argument's conclusion is what the person making the argument is ultimately trying to convince you of, i.e., the person's point. To try to identify the conclusion of an argument ask yourself 'what does the person making the argument want me to walk away thinking?' (Note if the answer is 'nothing', them you're not dealing with an argument.) Some Conclusion Indicator Words: therefore, consequently, as a result, thus, it follows that, so 2. Analyzing the premises Identifying the Premises: To try to identify the premises of an argument ask yourself 'what reasons is the person giving me to accept his point?' Some Premise Indicator Words: since, because, given that Missing Premises and Conclusions: When trying to figure out what the premises and conclusion of an argument are, we need to ask ourselves what the person's point is. But remember that people don't always come out and say what their point is. Similarly people may not always explicitly mention all the premises they are working with. As a result, we must be prepared to identify both missing premises and missing conclusions (i.e., conclusions or premises that are not explicitly stated by the arguer, but that are implicit in what the arguer does say). How are we supposed to tell what the arguer has in mind if he or she doesn't say it? By assuming person making the argument is rational and reasonable, e.g., that she holds the position she does because she thinks she has good reason to believe it. If an argument seems incomplete, we must ask ourselves what assumptions it is reasonable to think the person must be relying on. That is, what must this person believe in order to think she has made a coherent argument? Consider the following argument: I've never had any problems with the last four Fords I've owned, so my new Ford should be reliable. Obviously that breaks up into P1: I've never had any problems with the last four Fords I've owned C: My new Ford should be reliable 3. Clarify the language: Ambiguities make logical argument impossible. Identify the key definitions upon which the argument rests and recast any uncertain language. 4. Eliminate the excess: Remove anything which may distract from the actual argument; eliminate any prejudicial language in favour of a neutral wording. Remove clutter, such as universally-accepted definitions or assumptions (be careful of these). 5. Classify statements: Statements can be either statements of fact (something known to be true) or statements of opinion (personal view); distinguish between the two.